Piano playing shouldn’t be an olympic activity, yet players are regularly pitted against one another in international music competitions. Alongside this, is an ongoing argument about what are the hardest pieces in the pianist’s repertoire.

In his book ‘Play It Again’, Alan Rusbridger claimed that Chopin’s First Ballade was “one of the most difficult pieces in the repertoire”; it’s not, and taken alongside the Second or the Fourth Ballade, or indeed some of Chopin’s Etudes, it seems quite benign in comparison. Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit and Balakirev’s Islamey are also up there in the top 10 of “most difficult pieces”, along with Schumann’s Toccata, Alkan’s Concerto for Solo Piano, Beethoven’s ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata, Messiaen’s Vingt Regards sur l’enfant Jesus, Ronald Stevenson’s Passacaglia on DSCH, Sorabji’s Opus Clavicembalisticum, Ives’ ‘Concord’ Sonata. Ligeti’s Etudes, and Boulez’s Second Piano Sonata. There are many more pieces from the core canon which would slot neatly in to the “hardest piece” category, not to mention contemporary works which can be impenetrable except to the most skilled and intellectually-acute pianist.

In a way, all this is relative, because each pianist has his or her own strengths when it comes to repertoire. There are of course some performers who seem to be able to tackle anything – the late Sviatoslav Richter is one example. He had an incredibly large and varied repertoire, running to some “eighty different programmes, not counting chamber works”, from Handel to Hindemith and he worked indefatigably to learn new pieces. The Canadian pianist Marc-André Hamelin is another example. In addition to the standard works, he has a penchant for the more esoteric or lesser-known corners of the repertoire and seems to positive relish the most finger-twisting works.

Young performers entering the profession seem to think they should be able to play everything and anything. Perhaps this is what concert promoters and audiences demand, and it is interesting to find many young performers coping comfortably with the complexities and athleticism of Islamey, Gaspard, Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto, Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes and more.

Many people think the faster the piece the harder it must be, and audiences are often more impressed by flashy vertiginous virtuosity and piano pyrotechnics above beautiful sound or the ability to create a remarkable sense of communication and connection between performer, music and audience. I remember once showing one of my students a piece of piano music which consisted of just a handful of carefully-placed notes on a single stave. He was intrigued to learn that I was performing the piece in a concert the next day and declared that it couldn’t possibly be a concert piece because “it doesn’t look difficult enough”.

Too often we associate “difficult music” with concert repertoire, and while many pieces which are heard in concert are difficult, many are also well within the reach of the competent amateur pianist. (Indeed, no music should be “off limits” to anyone, though many amateurs are reluctant to tackle pieces they’ve heard in concert, believing, mistakenly, that this repertoire is the exclusive preserve of the pros.)

Very well known repertoire can be the hardest to perform because the music comes with a long heritage of previous “great” performances and recordings which can be stifling for the performer seeking to say something new, different or personal in the music.

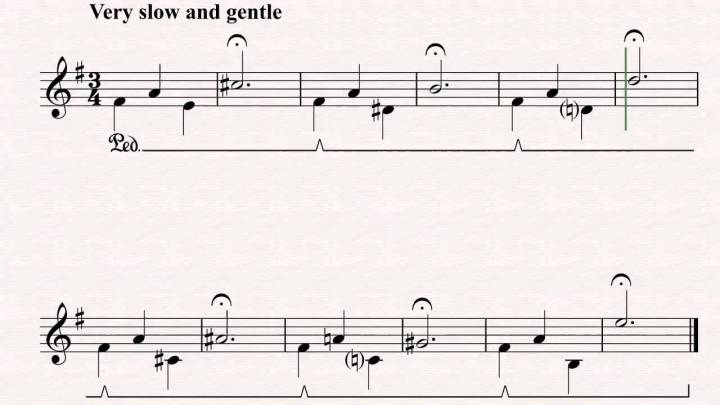

“Easy” music presents its own problems too. Pieces such as the one I showed my student (‘Just Before Dawn’ by British composer Paul Burnell) may be comprised of only 24 notes, yet it must be voiced with care and thought to convey the composer’s message. Music like this offers the performer nowhere to hide, unlike the dark thickets of notes one finds in an Etude by Liszt for example. Music whose dynamic range is very muted is also challenging, but it can have a remarkable effect of encouraging very concentrated, careful listening by the audience, drawing them into the inner circle of the performer’s own special soundworld.

Repertoire can be very personal. Most of us choose to play music we like rather than music we feel we should be playing – though of course professionals may “play to order” to satisfy a promoter’s request. I have noticed a certain competiveness about repertoire within piano meetup groups (amateurs can be quite olympian when choosing repertoire!) which can be perceived as “showing off” and may intimidate less advanced players. There’s a lesson here – that one shouldn’t constantly compare onself to others and that one will enjoy one’s music and play better if one focusses on one’s own strengths. I have been guilty of this myself and it made me very unhappy for awhile. Why couldn’t I play Ravel’s Jeu d’Eau or Sonatine (both works which I really like) when others could? I realised that some people are just better suited, physically and mentally, to this kind of repertoire, and that maybe my own strengths lie elsewhere.

Your “hardest piece” may not be my hardest piece, and vice versa, and being accepting of our own capabilities and strengths is an important part of our musical and artistic maturity.

If you enjoy the content of this site, please consider making a donation towards its upkeep: