By Michael Johnson

The quirky mind of composer Erik Satie continues to inspire, amuse and annoy us 100 years after his death, and musicians still cannot quite decide what to make of him. For sure, they can’t ignore him, if only because his monumental Vexations is returning from obscurity in lengthy performances and recordings by well-known keyboard artists in Europe, the United States and Asia.

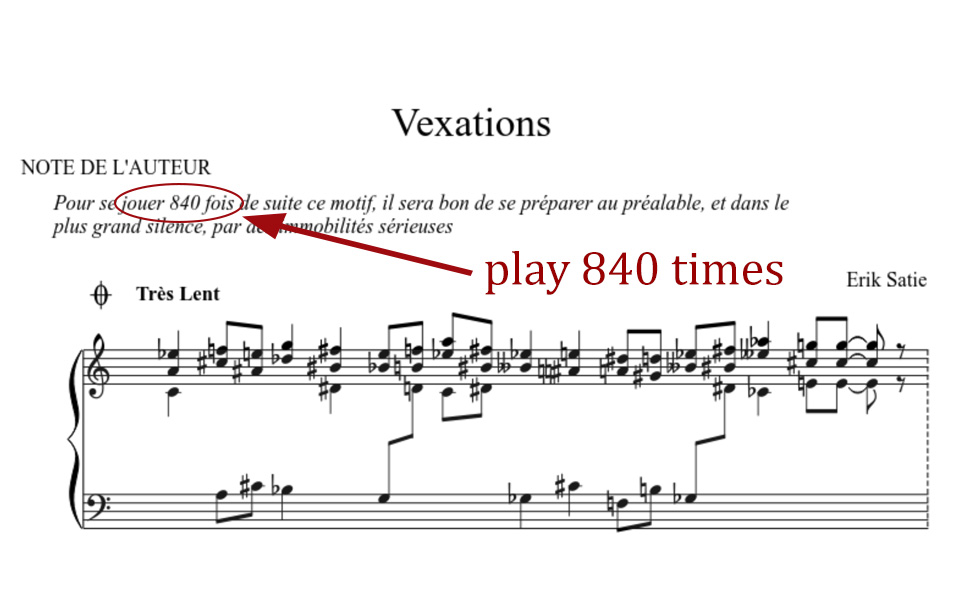

Igor Levit gave pianophiles a rare musical treat at the Southbank Centre in April 2025, leaving the hardy spectators in the audience mentally exhausted after 840 repeats of this one-page bagatelle. He took four or five short “loo breaks”, but kept himself going onstage with bottled water and a bowl of grapes. (He had previously livestreamed the work from the B-sharp studio in Berlin during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 in what he described as “a silent scream” to highlight the plight of artists hit by lockdowns.)

Levit kept his bearings during his Southbank centre performance by showing up with a bundle of photocopies of the score, discarding one at a time as he plowed through the piece. By the end, the stage floor was covered with 840 scattered copies.

Here is the haunting melody Satie created :

Wrote one spectator: “ I was at Queen Elizabeth Hall just to witness his performance. It was so, so, so intense!”

A couple of years earlier, the young Italian pianist Alessandro Deljavan had sat in the studios of record company OnClassical in Pove del Grappa, filling 12 CDs in 14 hours 28 minutes. He recalled the “intense experience” for me recently. “I felt almost possessed. My mind drifted between shadowy, undefined figures and total emptiness.”

Other pianists also remember hallucinating, and one reported seeing what looked like “animals and things” peering at him between the notes on the sheet music.

One commentator on YouTube ended up deeply conflicted: “This is actually an empty song. Nothing makes sense … Illogical. Sad. Devoid of feeling. I loved it.”

An English critic found the best poetic language. It is a piece of “meandering melancholy,” he wrote. Others report a “spiritual transcendence” evolving from the strange world Satie had created.

OnClassical founder and pianist Alessandro Simonetto is in the process of completing the most extensive project ever devoted to Satie’s complete piano works. Progressively appearing online, he says, it has already reached 30 million streams on Spotify.

Simonetto, a Satie enthusiast of note, calls Vexations “arguably the most extreme and elusive work in the entire history of music”. Living and working out of Pove del Grappa in the province of Vicence, he may eventually bring out a boxed set covering Satie’s complete piano works including at least the one page sample of Vexations. At the moment the project exists only digitally.

Simonetto presided at the marathon recording session with Deljavan, recalling for me that the experience was like an Edgar Allen Poe horror story, with the“ceiling slowly lowering on the pianist’s head”.

Yet the unlikely attraction of this longest piece in piano history refuses to die. More than 20 CDs have appeared in the past few years offering Vexations in part or in full, straight or modified versions. Two prominent French pianists, Jean Marc Luisada and Jean Yves Thibaudet have performed the piece, with all repeats.

Most reviewers have judged the full Vexations experience an endurance test, a prank or a stunt that Satie just tossed off without a second thought. He was known in the creative ferment in 1020s Paris for his musical jokes. He seems to have slid it into a drawer and never heard it played.

It’s the mental strain of non-stop repetition that leaves today’s pianists limp as a wet rag, except for Deljavan and the remarkable Levit. Indeed, Satie advised all pianists who try the full version to devote 20 minutes of silent meditation before starting. This became a feature of many modern performances.

But about 40 years ago English pianist Peter Evans played Vexations non-stop for 15 hours, suddenly quitting at repeat No. 593, and hurriedly left the stage without explanation. He later wrote that “people who play it do so at their own great peril”. The performance was completed by another English pianist, Linda Wilson. She later wrote that with each iteration Evans felt his “mind wearing away”. Observers wrote that when he left the stage he was “in a daze”. He recalled that his mind was filling with “evil thoughts”.

A notorious and frustrating episode occurred at Leeds College of Music in 1971 when another team of pianists managed to keep going for 16 hours and 30 minutes, ending at midnight only because school regulations closed the building. One of the team players, Barbara Winrow, explained to a journalist the “real sense of frustration which we felt, and the players’ remarkable reluctance to stop” before they reached the 840 mandated repeats.

A memorable milestone was reached in 1974 in Budapest when a team of pianists played in rotation for 23 hours. The team included at least two young players who went on prominent careers and are still performing today, Zoltan Kocsis and Andras Schiff.

Tracing the chequered past of this work is a major detective job. Musicologists return to the mysterious origins periodically. The manuscript was not played in full until more than 20 years after his death. Who acquired it, when, where, how or why did it change hands? Lawyers today call it a task of establishing the “chain of provenance”.

After gathering dust for years, it came back to life in the hands of John Cage who rescued it and encouraged others to participate in rotations. He first published the one-page treatment in the magazine Contrepoints in 1949. He was the first to interpret Satie’s written instructions as meaning the 840 repeats must be played without interruption – either solo or in rotating teams of pianists.

Cage organized the first public performance of the full version with more than a dozen pianists in rotation. His spectacle in 1963 in New York put his team through 18 hours and 40 minutes of continuous repetition.

But can it be played from memory? A vide on clip on Youtube shows Cage declaring that he was never able to memorize it. Other pianists have found it so contrary to accepted compositional norms that they could not absorb it either.

The late English music scholar Richard Toop performed the piece in its entirety several times but took care to approach each run-through with a fresh eye. But he too had a memory block. “Even after a performance,” he wrote, “I was unable to play more than a few beats from memory.”

Tracing the people who had possession of the original score, passing it from hand to hand, is impossible today due to the passage of time and the individuals involved. It is said to be with the Satie Archives in Honfleur, in the Calvados Department three hours northwest of Paris.