Guest post by Dakota Gale, part of his Notes from the Keyboard series for adult amateur pianists

Back in 1970, when my mom was 18, she composed the first section of the only piece of piano music she’s ever written.

Perhaps inspired by copious amounts of listening to Debussy and Satie, the music just poured from her fingers one day when she sat down at her piano.

At the time, she was in college in Madison, WI and in love with Robert, her first serious boyfriend. The piece starts off sweetly, brightly, a happy time in her life. The happiness shines from the first notes.

She’d taken piano lessons when she was younger, but never studied composition. She never wrote down the music, but it lodged in her hands and head.

Like mother, like son. (A drawing of mine.)

My mom graduated from college a couple of years after she wrote the first section. She and Robert planned to head to Santa Fe together and get married, but first he needed to work in construction for a bit to earn money for the move.

My mom headed south ahead of him to get situated in Santa Fe and start job hunting. A month, two months passed, but Robert didn’t show up. She wrote him letters, no response. Had he changed his mind, broken up with her?

Finally, a letter arrived. But not from Robert—from his mother.

He’d died in a construction accident.

Devastated, her world spun around and plans shattered, soon afterwards my mom wrote the second part of her composition. It’s a faster, darker section, an outpouring of grief after a sudden key change.

Years passed. My mom got a teacher’s certification, moved to Idaho, lived in a tipi and taught art.

Then she went to a national ceramics convention and met a bearded artist from California. A romance followed and they got married and moved to a defunct commune outside Chico.

Little Dakota popped out into the world not long after.

42 years later during a snowy walk in Bend.

Around this time, she composed the third section of music for her piece. It’s sweet, my mom in love again. The innocence and freshness of it is apparent. Cheery, fast and impetuous, full of expectations.

Who knows, maybe it flowed from her fingers while she was pregnant with me? She can’t remember the exact timeline.

Regardless, I recall her playing it occasionally when I was younger. After years away from the piano, she could perform it beautifully at any moment.

When I started learning piano, I wanted to learn the piece, but there wasn’t sheet music… Until this past week, that is!

On a rainy afternoon during her recent visit, we worked through the chords together and I explained the harmonies and sudden key changes that she’d chosen. She’d never learned music theory and didn’t know which chords she’d picked or why—all the music came straight from The Muse.

Sorting out the piece. Check out the stained glass in the background that my mom made for us—lady of many talents!

The only things missing were a final chord or two, so we played around with options before landing on something she liked. After some work, I fully transcribed the piece to sheet music—a first for me.

And so I’d like to present In Search of Lost Time by my mom. If you’re a pianist, you can download a PDF of the sheet music via Dropbox and play it! (Please forgive any newbie sheet music notation mistakes.)

Here’s a recording of my mom playing her piece, 54 years after the initial idea bubbled up from her consciousness:

The end of a special project together.

When he isn’t playing piano, Dakota Gale enjoys learning languages (especially Italian) and drawing. He also writes about reclaiming creativity as an adult and ditching tired personal paradigms in his newsletter, Traipsing About.

He can often be spotted camping and exploring mountain bike trails around the Pacific Northwest.

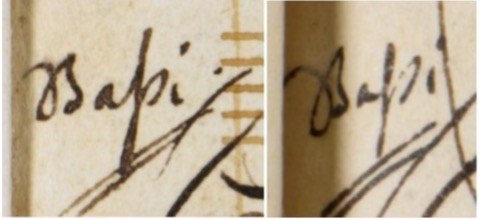

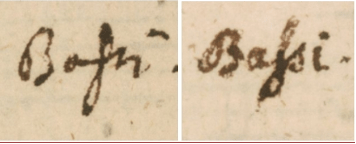

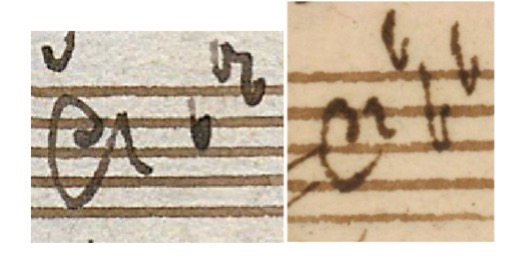

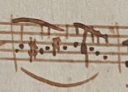

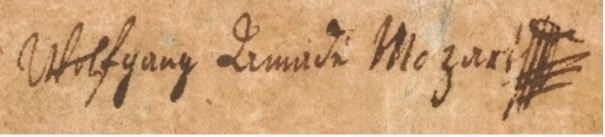

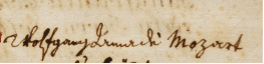

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.