Guest post by Ann Martin-Davis, pianist and teacher

‘Dum diddle diddle dum dum dum.’

How can it be that this simple tune that we all know isn’t counted in three? Yes, you heard me, not in three, but in fact in four plus two.

Try it out right now in your head – go on – and then go through all those other Baroque minuets that you have been humming for years and you’ll see that the shape of the melodies and the articulation that follows fall into the same pattern.

Now fast forward 200 years to Ravel; Menuet sur le nom d’Haydn, the Sonatine, Menuet Antique, and you’ll find the same patterns, and why? Because this is how it’s danced.

Learning the dances of the Baroque period doesn’t just sort out your understanding and playing of these composers, but it can inform pretty much everything else dance related that you might be involved with.

I’m with the dancer and historical coach Chris Tudor, and I’m joined by harpsichordist Sophie Yates, and Bach specialist, Helen Leek. We’re here to learn some of the basics and after intros in our ‘comfortable clothing’, we’re warming up with a simple hand held chain called a linear carole.

Caroles, or carols as we now call them, always used to be danced and sung, but at some point we lost the dance element. The origins go way back to the ancient Greeks and to the choros, or circular sung dance. Remember the dancers on Achilles’ shield in Homer’s Iliad? The magic of the shield creates a moment of escape from the pressures of reality and of the battle; I too quickly forget my parking battle off the Euston Road and settle into the conviviality of it all.

Next up is a renaissance dance, the Branle, which Chris tells us is a surreptitious way of introducing some of the steps to a minuet. We take one step to the right, close, then one step to the left and over with the right. Always rotating clockwise as we don’t want any negative energy.

We make swift progress and then I drop the bomb.

‘How about a Courante?’

Chris grimaces a bit and at this point I suddenly have a flashback to a grade exam, where I galloped through a Bach Courante and landed with a grateful ‘ta dah-like’ placement of the final ‘G.’

Sophie steps in and tells me that the Courante was fast in the Renaissance, but by the time J S Bach got busy with it, the metre had moved to 3/2 making it one of the slowest of all of the Baroque dances. She continues, ‘it could be apocryphal, but gossip colomnist in Chief in Versailles, Titon du Tillet said it slowed down because of Louis XIV’s long-toed shoes, meaning an extreme turn-out was necessary.’

So the Courante gets us talking about the ‘cadence’ of a dance which can relate to two ideas. We have cadence, as in the cadence of your voice, the qualities of the dance (a Courante has a noble and stately quality), but there is also the exploration of the cadences in the music and how these are going to relate to the cadences in the dance.

This is blowing my fuses now, so we all agree it’s time for coffee…

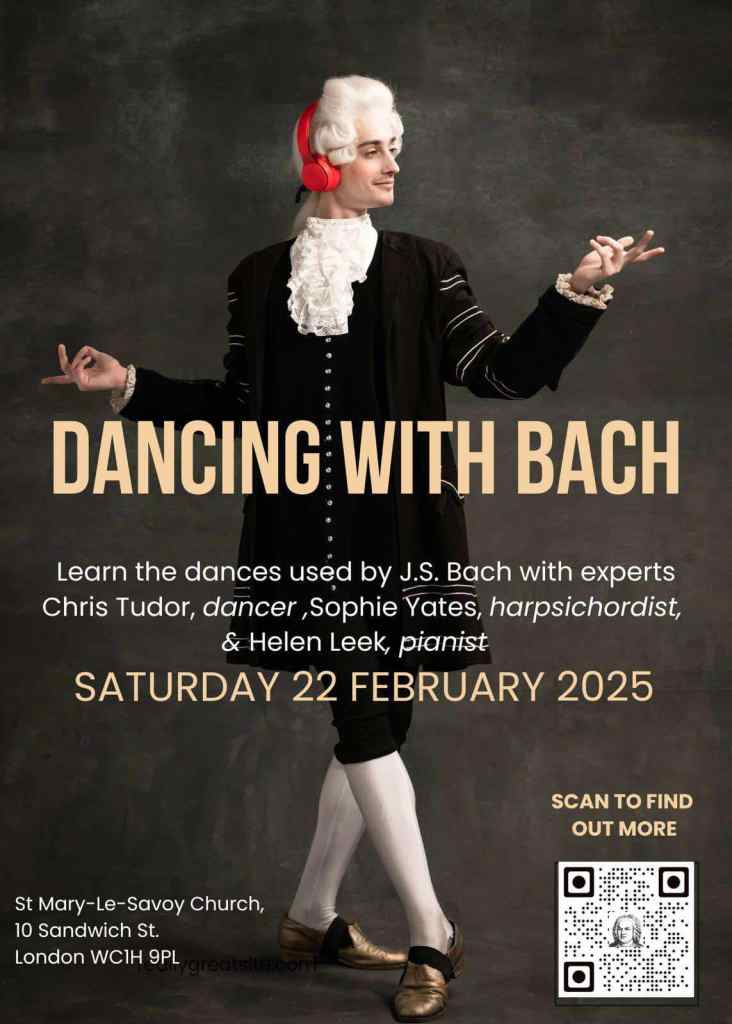

‘Dancing with Bach’, hosted by Ann Martin-Davis, with Chris Tudor, Sophie Yates and Helen Leek is a one-day workshop for pianists exploring the dance forms familiar to Bach that he used in his Partitas, Suites, and throughout his other collections of keyboard music.

Saturday 22nd February at St Mary-Le-Savoy Lutheran Church, London WC1H 9LP

Bring your dancing shoes!