First published in 2013, The Musician’s Journey by Dr Jill Timmons is a handbook for musicians who want to make the most of their specialist training to carve a successful professional career.

A celebrated pianist, who studied with, amongst others, György Sebők, Jill Timmons is also an acclaimed educator and leading consultant in arts management and mentorship. Her profound appreciation of the sensibilities of musicians and the exigencies and challenges of the musician’s life – from physical and emotional health to the importance of self-care and personal autonomy – together with years of experience within the music profession, make her the ideal guide and mentor.

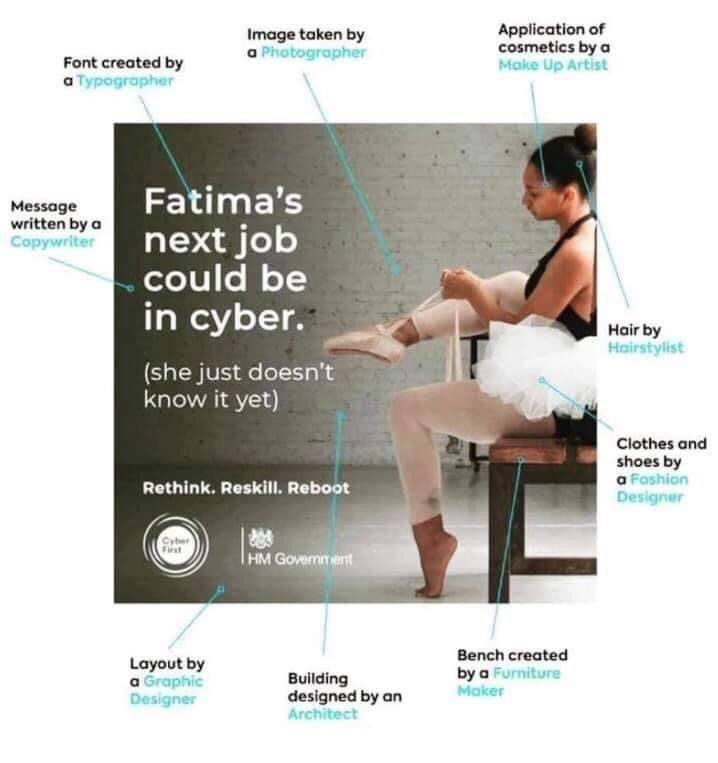

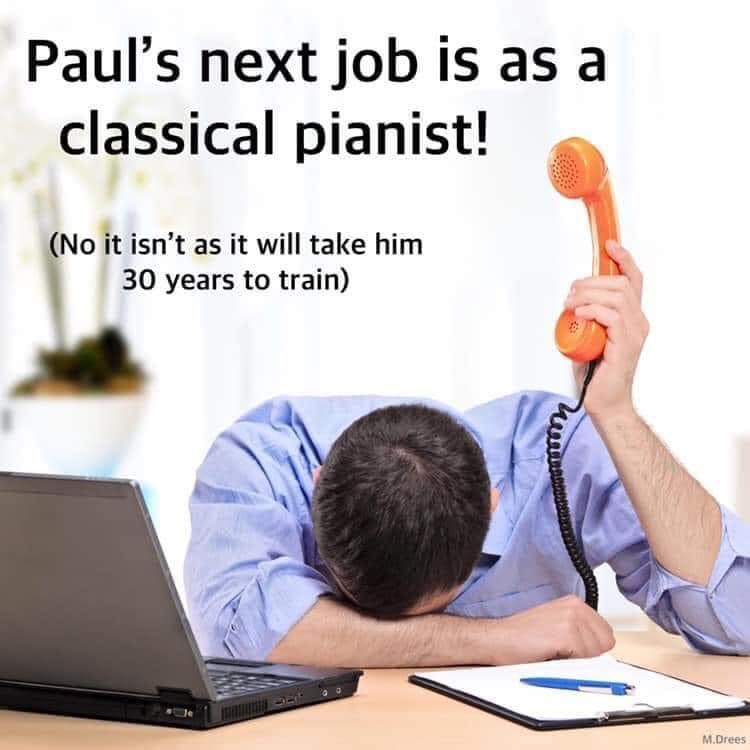

The musician’s training, usually undertaken at specialist music school and/or conservatoire, is still largely focussed on learning to be a performer. Yet, today more than ever in the highly competitive world of professional music, musicians embarking on a professional career (and even those already established) need a good handle on the business side of the profession. Little practical support or teaching is offered in the other important areas of shaping one’s professional career – from learning how to create a website or develop a social media presence to entrepreneurship, and business and marketing skills – leaving many musicians on graduation thinking, (and often being asked), “So what do you do now?”.

Unfortunately, an attitude still prevails that taking a more businesslike approach to one’s career “devalues” the music. Fortunately, Timmons successfully debunks this absurd notion in The Musician’s Journey, and offers a wealth of practical information, inspiring case studies, and insights drawn from personal experience to help musicians develop, enhance and broaden their careers while retaining a strong self of personal autonomy, individual integrity and artistic vision – themes which run, fugue-like, throughout the book.

Organised in short, focussed chapters, with clear subject sections within each of them, and written in an accessible, conversational style, Timmons draws on numerous resources from religion and mythology to neuroscience, physiology to Feldenkrais, and much more, to illustrate her approach. This is not a self-help book in the traditional sense, and it is refreshingly free of “woo woo” pseudoscience and cod coaching. Instead, Timmons presents a meticulously researched, highly readable and non-elitist handbook which takes the reader on a detailed journey with specific goals and plans showing how to steer a path through the myriad complexities of the profession.

Too much is written on practicing music, finding one’s creative voice and finessing one’s performance skills; too little is written on the practicalities of forging a career in music (and in the arts more generally) in the 21st century. This book is a sensible yet inspiring manual on how to live a vibrant, fulfilling and successful life as a professional musician. Timmons gives much pause for thought with ideas and suggestions musicians may not have considered before, or were discouraged from considering during their training. In encouraging a good portion of “thinking outside the box”, Timmons’ book will also appeal to people outside the profession: her pragmatic and inspiring approach is applicable to anyone embarking on a freelance career.

Key points

- Offers a strategic combination of creating a vision and then formulating a plan to help guide musicians in successfully developing a thriving career

- Includes diverse true-life stories of music professionals who have used the process successfully

- Focuses on entrepreneurship as a means for career development

- Suggests general tips on grant writing and financial development

- Guidelines for teaching entrepreneurship

- In addition, the updated second edition considers the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of musicians, and the arts in general

Additional resources, including downloadable forms and worksheets, are available from the book’s companion website

The Musician’s Journey (second edition) is published by Oxford University Press