Playing Debussy on his Blüthner

Playing Debussy on his Blüthner was a ‘head-spinning experience’ – guest article by Michael Johnson

French pianist François Dumont has still not quite recovered from ‘the excitement, the anxiety’ of playing “Clair de Lune” on Debussy’s own Blüthner piano in a remote French museum.

Dumont is one of the select few pianists ever allowed to touch the instrument, now fully restored and in mint condition. It was his credibility as a Debussy player that persuaded museum management to grant access.

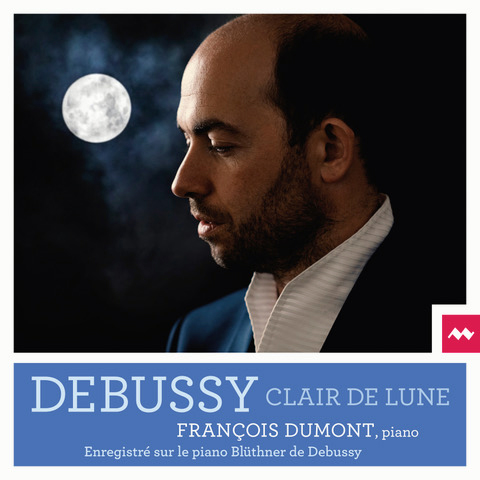

Dumont has just released his new CD of Debussy piano music (Clair de Lune LaMusica LMU035) played on the vintage Blüthner at its resting place in the Labenche Museum in Brive-la-Gaillarde, not far from Bordeaux.

He recalled in our interview (below) how it felt to press a few keys the first time. ‘I sat down and timidly put my fingers on the keys… and it was just magical!’

The sound is indeed unique to the modern ear, a resonance intentionally soft and continuous, unlike the more glassy pedaled attacks of a Steinway grand. Dumont says changing to a nineteenth-century Blüthner is fascinating and deeply satisfying musically. Personally, I grew accustomed to his recording only after four or five hearings.

He puts the Blüthner to work on selected parts of Debussy’s Bergamasque Suite, Estampes, and Children’s Corner. His sensitive playing is as touching in the pianissimo as in forceful fortissimo. He recalled for me that he did several takes of “Clair de Lune” before he was satisfied. ‘I repeated it until I found the ethereal colours, the warmth of the melody I was looking for,’ he said.

Dumont thus joins a stellar group of established Debussy interpreters from the twentieth century and more recently performers such as Daniil Trifonov, Angela Hewitt and Steven Osborne. A busy recording artist, he has made about 45 CDs across a wide range of repertoire..

Dumont’s talent is in great demand in Europe where he maintains a punishing schedule of solo recitals and ensemble dates, as well as chamber orchestra works, in the United States, Latin America, China, Japan and South Korea.

Here are excerpts from our email exchanges about the new Debussy CD and the original Blüthner piano featured on it:

How long had this ancient Büuthner piano been idle? Shouldn’t it be falling apart?

Debussy bought the Blüthner in 1904 and kept it until his death in 1918. It was acquired by the Labenche Museum in Brive in 1989 and was fully restored, keeping the original strings and most of the original action

Are you the first pianist to be granted access to it?

There have been some others but very few. For me, it was an unbelievable privilege – a head-spinning experience – to have had access to it.

How were you chosen?

One needs to have real credibility and experience in playing Debussy to get the authorization. The museum generously offered me the use of the piano for the CD.

What is your memory of first sitting down and touching the keys? Were you nervous, excited, worried, afraid?

I will never forget that moment. I had travelled all the way from Lyon, over four hours by car, just to try the piano for an hour. I was very excited but also anxious. How would it sound, in what state would I find it? Would I feel comfortable creating my own sounds? I was afraid of being disappointed. I didn’t quite know what to expect.

It must have been a kind of electric feeling.

Yes, I sat down and timidly put my fingers on the keys… and it was just magical! I played my whole program without stopping. I was completely drawn to the originality and variety of colours.

Did you feel a spooky connection with Debussy, his ghostly presence hovering over you?

Yes, I suddenly felt I was transported to Debussy’s time, hearing the sounds as he was hearing them, playing the instrument he was playing. It is actually quite intimidating. Just imagine, some of the works on my CD, like “Children’s Corner”, were probably composed on this very instrument. A considerable amount of his music was seeing the first light of day on that Blüthner. It must have been like a laboratory for him.

How has the Blüthner design evolved since the 1850s?

The design and mechanics have indeed evolved, together with the sounds aesthetics, style and repertoire. Of course there is the question of parallel strings; now Blüthner uses crossed strings, like almost all modern manufacturers.

Why is the “fourth string” so important?

One of the specifics of the Blüthner piano is that string, called the Alicot. In the high register, instead of three strings, you find a fourth one that is not struck by the hammer. It resonates freely, by sympathy. creating a richness of color and vibration across all 88 keys.

How do you rate the Bluthner compared to the more dominant brands?

One has to remember that at Debussy’s time Blüthner was one of the most prominent brands, together with Bechstein, Erard and Pleyel. I find that Debussy’s Blüthner has a very beautiful range of colors, from bright to mellow to dark. It offers much more individuality than many modern instruments.

But isn’t it a smaller model, intended for the salon, not the concert stage?

True, when it comes to dynamic power you cannot compare it to today’s main brands. It is a chamber instrument, not even a half grand. It suits perfectly the room where it is now, surrounded by the museum’s beautiful tapestries.

What is the real value of the fourth string?

I am very seduced and intrigued by it, as it adds an element of resonance, a way of blurring the sounds, in the good sense. It is ideal for, let’s say, Romantic or Impressionistic music. I am not sure it would suit Baroque or Classical repertoire as well.

Does this fourth string alter other aspects of your playing, such as pedaling, control of dynamics or intense listening as you play?

Absolutely, many aspects are affected. Principally, you actually don’t need heavy pedaling, as you have a natural aura around the sounds. So you can keep precise pedaling, or sometimes experimentiation, to create really astonishing, impressionistic effects.

Don’t you have to work hard to control the sound you produce?

Yes, you have to listen very attentively, as the resonance is sometimes unpredictable. It is quite capricious, so you constantly need to adapt, which is artistically challenging but also very inspiring.

What musical qualities have you been able to draw from the Blüthner that you could not create with, say, a Steinway?

Well, the Steinway is so perfect, even, smooth and powerful at the same time, with absolute tone control. Debussy’s Blüthner is quite the opposite – capricious, uneven, with a very different character to each register. There is always a surprise with the Blüthner, which creates an element of risk which artistically pushes you to go further. For “Clair de Lune”, which we recorded at night, I had to do several takes till I found the ethereal colors, the warmth of the melody I was looking for. This piano has a unique vibration and warmth. You can really make it sing.

How did the piano affect your interpretations of the three Debussy cycles you chose for your CD?

I felt I was inspired to be freer, with more personal rubato and more creative with colors. On this piano you can really paint the tones.

But you cannot push it to produce, for example, the Russian School of “fast and loud”?

No, it cannot provide huge power but you can achieve many pianissimo dynamics, and subtle changes of sound and articulation. I also realised that some of colors were quite bright and contrasted, not just the pastel qualities usually associated with Debussy. This instrument taught me a different aesthetic, and pushed me toward greater flexibility and individuality.

Will other pianists be tempted to apply for access ?

Yes, I am sure that other pianists will be tempted by this wonderful adventure which brings us closer to Debussy and gives some insight into the interpretation of his works.

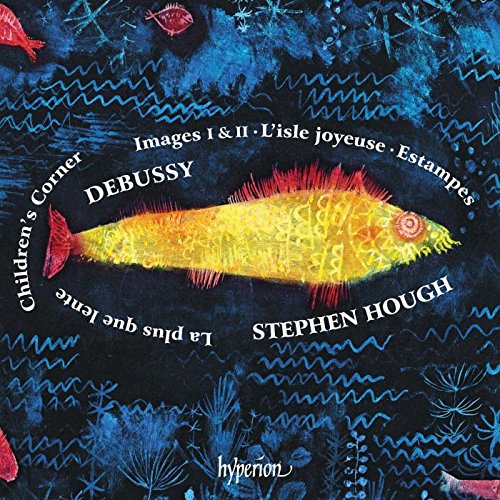

…….make sure it’s Stephen Hough’s new disc of piano music by Debussy (Hyperion).

…….make sure it’s Stephen Hough’s new disc of piano music by Debussy (Hyperion).