‘The World of Yesterday’ – written & performed by Sir Stephen Hough with the Bournemouth Syphony Orchestra, conducted by Mark Wigglesworth. Wednesday 26th February, Lighthouse, Poole

British pianist Sir Stephen Hough hadn’t intended to write a piano concerto. But during the dark days of the COVID pandemic, he was approached to write a score for a film about a concert pianist writing a piano concerto… With little to do but take Zoom calls, “it seemed like a wonderful way to keep me busy”, and, intrigued by the film’s plot, he began jotting down ideas.

As the world emerged from the pandemic, the film project stalled and Stephen’s concert diary began to fill up again, but he still had the sketches for the film score and, with the support of four orchestras (the Utah, Singapore and Adelaide symphonies, and the Hallé) he wrote his piano concerto ‘The World of Yesterday’. It received its world premiere with the Utah Symphony Orchestra in January 2024 and a recording made with the Hallé and Sir Mark Elder is available on the Hyperion label.

I had the pleasure of hearing Hough perform his concerto with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra in a well-conceived programme called Notes of Nostalgia. Given its theme, the concerto sat perfectly between Brahms’ Third Symphony and Elgar’s Enigma Variations – all three works infused with a certain wistfulness interposed with personal reflection, warmth and wit.

Hough’s concerto takes its inspiration, in part, from Austrian author Stefan Zweig’s atmospheric memoir of the same name, which depicts Vienna and Viennese culture in the last golden days of the Habsburg Empire before Europe was torn apart by war. You can almost smell the aroma of Viennese coffee and taste the Sacher-Torte in the quieter passages of the piece.

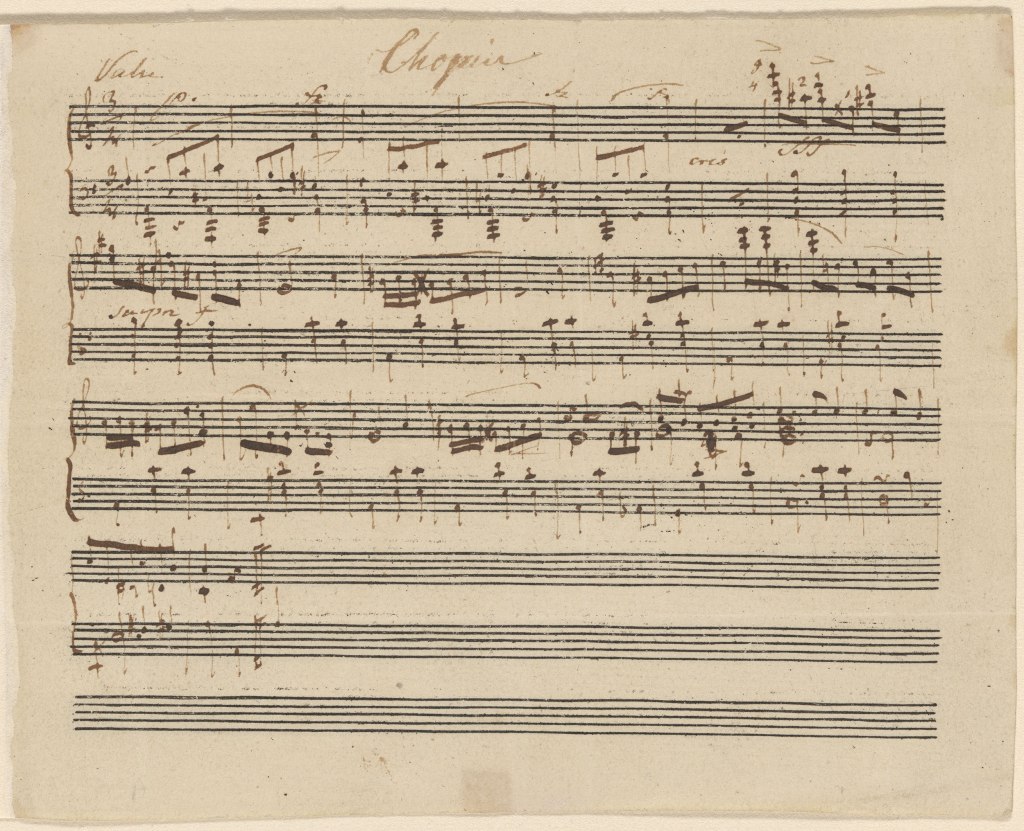

The music is rich in nostalgia, but without the heart-tugging poignancy of Chopin, for instance: it’s a more reflective yet positive reminiscence of another time. Scored in a single movement but with distinct sections, ‘The World of Yesterday’ has a filmic quality (“something from the 1940s”, my husband commented as we left the concert hall) – you certainly hear nods to Korngold’s film scores, and it shares Korngold’s romantic sweep, but there are also references to Rachmaninov (particularly in the very glittery virtuosic solo sections), Copland, the Warsaw Concerto…but at no point do these references feel like pastiche. And if you’re familiar with Hough’s wonderful transcriptions of Rodgers and Hammerstein, you’ll find similar idioms here (I half-expected Hough to segue into the Carousel Waltz at one point). And yes, there is a waltz too – not so much a Viennese waltz but something more sultry, redolent of Bill Evans and a smoky, late-night jazz club.

Hearing the composer play his own work was like a bridge across time to another world of yesterday, a time when composers wrote piano concertos which they performed themselves: Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninov and Prokofiev all performed their own concertos. Showcasing their prowess and personality as both performer and composer, these works becoming their “calling cards” as they toured to give concerts.

The music has an almost “vintage” quality: surprisingly traditional in its direct communication with orchestra and audience, and its idioms, motifs and references to other composers (there’s not a hint of that “squeaky gate” atonality one often associates with contemporary classical music). The piano enjoys Brahmsian interactions with the orchestra and Rachmaninov-esque cadenzas, but Hough’s does break with tradition in a few significant ways. First, the concerto has a narrative title, rather than just an opus number or key, which undoubtedly guides the audience, even without a programme note. Additionally, the cadenza, traditionally heard at the end of a movement, comes very early, after an orchestral ‘prelude’. Here the piano is solo, notes and motifs sparkling in the upper register (later mirrored by the piccolo).

Above all, The World of Yesterday is a richly textured, virtuosic and joyful celebration of past influences, rather than a poignant glance back to a better time. It’s full of warmth and wit, affection and humour: it made me smile, it thoroughly uplifted.

After all, isn’t that what music should do?

‘The World of Yesterday’ is released on 28 February on the Hyperion label