Guest post by Michael Johnson

Morton Feldman’s delicate, will o’ the wisp compositions demand a spiritual investment, a belief in music’s potential to enter the human consciousness almost unnoticed. The simplicity can be deceptive. One is tempted to say, as a young English mother whispered to me recently at a Feldman recital, “My ten-year-old could play this.”

Marc-André Hamelin and a large fan club disagree. Hamelin once told me that the first time be heard Feldman’s For Bunita Marcus he felt he was transported to an entirely new dimension. He was stunned, and went on to perform, and finally to record (Hyperion B06Y3L26GC) the entire one hour and twelve minutes of Bunita Marcus. Now I was stunned and transported.

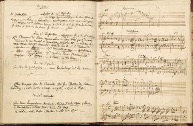

Here is the Feldman sheet music played by Hamelin.

Ivan Ilic, the Serbian-American pianist based in France, is also leading a renaissance of the Feldman oeuvre – dormant for decades. He says he might be tempted to retort to the mystified mother, “Madame, either you get it or you don’t.”

Ilic and Hamelin and I got it, profoundly, as a result of an effort to get into Feldman’s head and play him the way his work was intended. Ilic says he is determined to show the way to the rapture he felt, which he describes as wanting “the spell to continue … interruption seems unthinkable”.

His Bunita Marcus CD, ‘Ivan Ilic Plays Morton Feldman’ (Paraty/Harmonia Mundi), delivers a rarefied performance that gets to the very essence of music. “Nothing distracts from the backbone of single notes or quiet chords,” he wrote. In one of the tracks, Feldman creates a tremendous feeling of space, with a hollow chord in the left hand and only two notes in the right hand. “Few composers can do so much with so little,” says Ilic.

To quote poet Robert Frost, the minimalist playing enters your mind on “little cat feet”. Feldman and his mentor John Cage believed in the wisdom of India that says quietude in music can trigger divine intervention in the mind.

Feldman also saw a morbid side. He has written,“In my art I feel myself dying very, very SLOWLY.’ The last third of For Bunita Marcus’ is a wonderful illustration of that idea.

Ilic has attempted to describe in his liner notes the Feldman ceffect. “Ever patient, using the same notes, (Feldeman ) wears me down. Then slowly I start to forget my feelings. I hear the music again, but now it has a glow to it. My ears and mind have adjusted, and my ego fades into the background.”

Who was this enigmatic Bunita Marcus? They met at the University of Buffalo, in New York State, in 1975. She was a doctoral student in composition and her professor Feldman was clearly star-struck. No photos survive. “I am very enthusiastic about this girl,” he once said. “I think she is something to be enthusiastic about. I am never going to have another student like her as long as I live. Never.” Although he called her compositions “gorgeous and elegant” they left no trace in the repertoire. Nevertheless, his hour-long tribute guaranteed a certain notoriety.

Ilic admits that his first brush with Feldman left him feeling “edgy”. He says he felt that “the music isn’t going anywhere”. He warns that others might feel the same initial barrier. But his experience consisted of “puzzlement-tension-release-trance”.

He discovered that his sense of time could disappear. “The piece can last one hours, or four hours; I know I’ll follow it to the end.”

Feldman the writer published his music philosophy in a collection of his works, Give My Regards to Eighth Street. He offers this thought – that the “chronological aspect of music’s development is perhaps over, and that a new mainstream of diversity, invention and imagination is indeed awakening. For this we must thank John Cage.”

In the years following his voluminous oeuvre, he has proven to be at least partially right.

MICHAEL JOHNSON is a music critic and writer with a particular interest in piano. He has worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Moscow, Paris and London over his journalism career. He covered European technology for Business Week for five years, and served nine years as chief editor of International Management magazine and was chief editor of the French technology weekly 01 Informatique. He also spent four years as Moscow correspondent of The Associated Press. He is a regular contributor to International Piano magazine, and is the author of five books. Michael Johnson is based in Bordeaux, France. Besides English and French he is also fluent in Russian. He is a regular reviewer for this site’s sister site ArtMuseLondon.com.

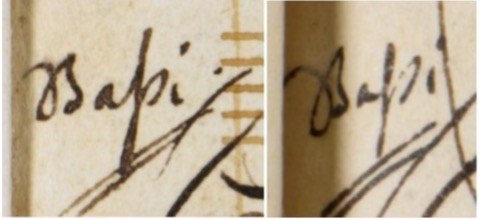

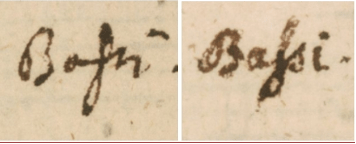

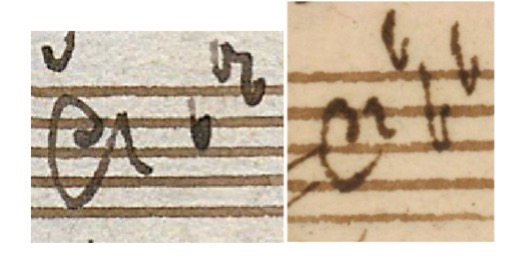

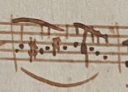

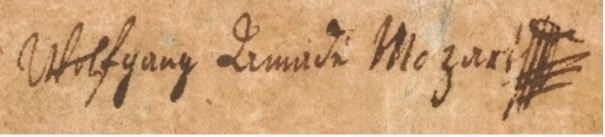

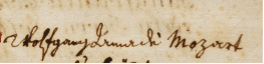

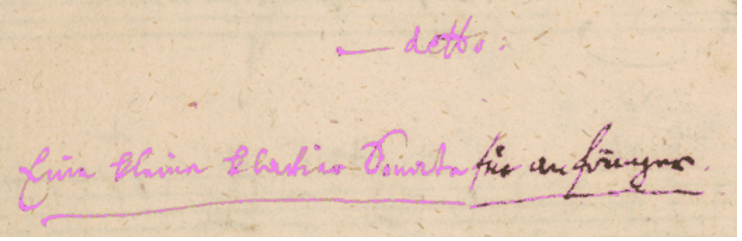

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.