Who or what inspired you to take up conducting and pursue a career in music?

The decision to become a musician was a gradual one; my first post – as organist at Brixton prison when I was 16 – showed that it was possible to be paid for doing what I enjoyed – and my first paid conducting performance (Messiah, when I was 17) further convinced me that this was a congenial way to make a living. It was Adrian Boult, however, who wholly changed my focus of ambition. I went to a concert of his in Oxford during my post-graduate year and suddenly became aware of what a conductor could achieve. I pushed a note under his door in the Randolph Hotel asking if he would take me as a student. Characteristically, he replied the next day inviting me to audition for his advanced course at the RCM and that began a learning process that continued almost until he died. He was unquestionably the most significant influence on my musical life.

What, for you, is the most challenging part of being a conductor? And the most fulfilling aspect?

The most challenging part of being a conductor in this country is that you’re almost always trying to work with a short amount of rehearsal time, so you tend to depend more than you should have to on your musicians being prepared to fill in the gaps for you. That is not the case in the United States and in Europe, where you are given more rehearsal time with professional musicians; the more relevant challenge there is developing the sense of urgency you need for a rehearsal without being over-demanding.

The most fulfilling aspect is the sense of making music with a number of other people, some of whom you’ve known for many years, and still deriving the same intense pleasure from doing so – in some 30 years after our first collaboration. Whether the players feel the same, of course, I cannot say!

As a conductor, how do you communicate your ideas about a work to the orchestra?

I believe the conductor’s job is to communicate as much as possible by gesture; too much talking is a well-known conductors’ disease. That said, offering an orchestra/choir what you hope are helpful images to clarify the sound or character that you are trying for can be beneficial if you can find the right metaphors.

How exactly do you see your role? Inspiring the players/singers? Conveying the vision of the composer?

A conductor needs to be both a manager and a bit of a visionary. Helping musicians to feel that what they do is important and worthwhile – and valued by the conductor – is important, but clearly the composer should be the fundamental reference point for all performers.

Is there one work which you would love to conduct?

There are several works I would like to conduct, which have so far eluded me: Walton’s First Symphony and Cello Concerto, Mahler’s Second Symphony and Morning Heroes by Bliss. More pressingly, there are works I would love to conduct more often – particularly Beethoven’s Glorreiche Augenblick, The Kingdom or the symphonies by Elgar and such neglected masterworks as the Holst Choral Symphony, and the marvellous tone poems by Bax.

Do you have a favourite concert venue to perform in?

I love both the Bridgewater Hall in Manchester and the Symphony Hall in Birmingham, though I also love Dalhalla in Sweden, which is an open-air venue – constructed out of a gravel pit – with a fantastic atmosphere and acoustic. The only drawback is that the conductor has to be rowed to the venue and I can’t swim.

Who are your favourite musicians/composers?

My favourite composers are always the ones I’m currently working on. When you’re preparing something for performance, it occupies the whole of the forefront of your mind and that means you are very closely entwined in what you hope to be the intentions of that particular composer at that particular time.

It is very difficult to identify favourite musicians; almost all of my colleagues are helpful and collaborative. You soon discover the handful who are not, and as far as possible you give them a wide berth. One of my absolute favourites, though, is the marvellous South African baritone, Njabulo Madlala. Brought up in Durban he has made his way to the forefront of the classical music scene purely on merit and a determination which never prevents him from being entirely charming and delightful.

We performed Elijah together four years ago in Leicester. He sang it wonderfully, and I’m thrilled to be able to do it again with him in the Barbican Centre on 13th February. Elijah is one of those works that has drifted slightly out of fashion – a real mistake, as it is full of inspired melody and dramatic invention. And, of course, it brings together professional orchestral players and soloists with one of our leading amateur choirs. A combination which often leads to the best result possible: professional expertise with amateur commitment and enthusiasm.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

Being the best possible conduit between the composer and the audience. If the audience leaves the concert saying what a wonderful piece they have heard, I think we’ve done the best we can.

What do you consider to be the most important ideas and concepts to impart to aspiring musicians?

Fidelity to the composers’ intentions. We live in a time of absurdly elevated personality cults; the job of the performer is to focus the audience on the composer’s personality and not his or her own.

Hilary Davan Wetton conducts the City of London Choir and Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in Mendelssohn’s ‘Elijah’ at the Barbican Centre on Tuesday 13th February at 7.30pm. Soloists are Rachel Nicholls, Diana Moore, Daniel Norman and Njabulo Madlala as Elijah. More information and tickets

Hilary Davan Wetton has been Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of the City of London Choir since 1989. One of the country’s most distinguished choral conductors, he was founder/conductor of the Holst Singers, and is Conductor Emeritus of the Guildford Choral Society and Artistic Director of Leicester Philharmonic Choir. He is also Associate Conductor of the London Mozart Players and Conductor Emeritus of the Milton Keynes City Orchestra.

Educated at Brasenose College, Oxford and the Royal College of Music, Hilary studied conducting with Sir Adrian Boult and was awarded the Ricordi conducting prize in 1967. Over a career spanning 50 years, he is particularly admired for his interpretations of 20th century British music, conducting many first performances for British composers as well as neglected works by Gardner, Parry, Holst, Dyson, Bridge, Sterndale Bennett and Samuel Wesley.

His extensive discography includes recordings for Hyperion with both the Holst Singers and Guildford Choral Society, a series of acclaimed recordings for Collins Classics with the LPO, including Holst’s Planets, Elgar’s Enigma Variations and Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony, and discs for Naxos and EM Records with the City of London Choir. He received the Diapason d’Or for Holst’s Choral Symphony (Hyperion, 1994). In Terra Pax: A Christmas Anthology (Naxos, 2009) reached number two in the Gramophone classical chart and enjoyed wide critical success. Beethoven’s Der Glorreiche Augenblick (Naxos, 2012) has also been much admired, receiving a five star review in BBC Music Magazine; and Flowers of the Field (Naxos, 2014) with the City of London Choir, London Mozart Players, Roderick Williams and Jeremy Irons went quickly to number one in the Specialist Classical Chart.

Hilary has broadcast frequently for the BBC and Classic FM. For six years, he was presenter/conductor for Classic FM’s Masterclass, and he was Jo Brand’s organ teacher for the BBC 1 series, Play it Again. He has been awarded honorary degrees by the Open University and De Montfort University and is an Honorary Fellow of the Birmingham Conservatoire.

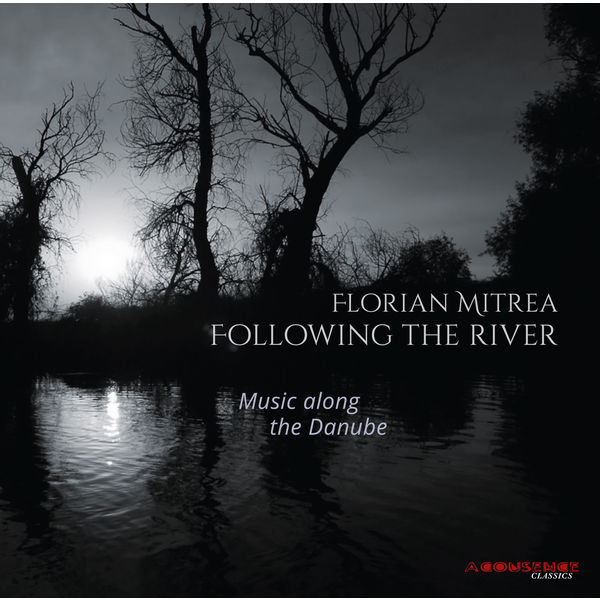

These two works appear on Florian’s debut disc, Following the River, inspired by childhood memories of “hot summer nights spent on a boat in the middle of a channel, deep in the heart of the Danube Delta” (FM). The Danube, the longest river within today’s European union, flows through 10 countries and four capital cities – Vienna, Bratislava, Budapest and Belgrade – and carries with it stories, folklore, memories and more. In Following the River we find quite a different version of the river from

These two works appear on Florian’s debut disc, Following the River, inspired by childhood memories of “hot summer nights spent on a boat in the middle of a channel, deep in the heart of the Danube Delta” (FM). The Danube, the longest river within today’s European union, flows through 10 countries and four capital cities – Vienna, Bratislava, Budapest and Belgrade – and carries with it stories, folklore, memories and more. In Following the River we find quite a different version of the river from