Guest post by Nick Hely-Hutchinson

If Beethoven were alive today, there has to be a decent chance – likelihood, even – that he would have been cured of the deafness which beset him for the last fifteen years of his life.

Of the various remedies which were suggested to him, and there were plenty, amongst them was the suggestion to use olive oil.

In Cornwall last year, I managed to collect some water in my left ear which refused to come out, with the result that by April this year I could barely hear a thing if I blocked my right one. Nearly two hundred years after the great man, I was also recommended the use of olive oil, but as a precursor to having the ear syringed, as the oil softens the wax and thereby reduces the risk of damage to the drum during the procedure.

Beethoven is unlikely to have collected too much water in his ear, for his personal hygiene was almost nonexistent. I am equally sure that it would have taken more than syringing to deal with his problem. But my own experience has given me the teensiest sense of what it is like not to hear properly.

Summing up the work of any composer in just one piece is not just difficult, it is verging on the daft. Beethoven’s enormous output in his miserable life had many landmarks, many ‘firsts’. His third symphony, the Eroica, changed symphonic writing for good. His ninth was the first to include a choir. I could go on…

But if I had to single out just one piece which summed up the core frustration in his life, it would be his 23rd (of 32) piano sonata, now known as the Appassionata.

Writing about music is notoriously hard, and, some would say, a little futile, because it is the hearing of it and the experience which is personal to each of us. Beethoven, however, who once quipped that he would rather write 10,000 notes than a single letter of the alphabet, speaks to us so directly in his music, and this piece in particular, that it is not at all difficult to understand its message.

Beethoven has something of a reputation for tumultuous, even ballsy music. Because of this, it is easy to forget that the man wrote some of the most exquisite and sensitive slow movements in the entire repertoire. It’s like a lion stopping in his tracks and scooping up a lesser mortal to tend and nurture, rather than trample or devour.

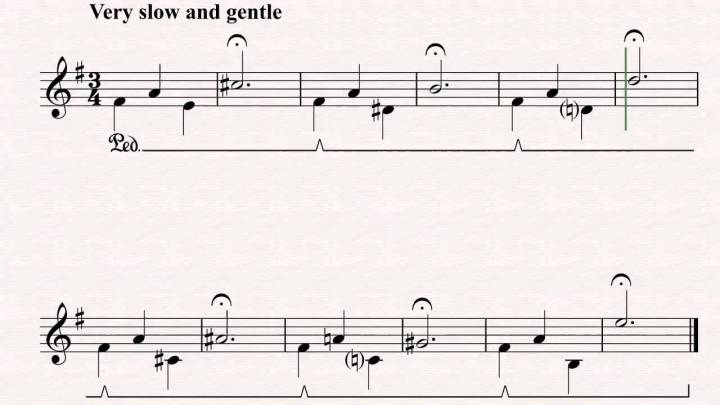

So today I’m giving you the last two movements of the Appassionata, played with appropriate passion and wonderful clarity by Valentina Lisitsa. It starts with a simple theme, followed by three distinct variations, before returning to the original. At first it may seem a little pedestrian, but as it unfolds, Beethoven’s mastery of counterpoint, the ability to have two or more tunes singing at the same time, comes to the fore. It becomes five minutes of pure tenderness, which grow on you each time you hear it. As it comes to its close, Beethoven launches straight into the final movement without a pause.

This is Beethoven ranting at the world at the loss of his hearing. Listen to that circular motif after the first few seconds, which remains a theme throughout: it is the cry of an anguished man, pacing up and down in his room. Anger; frustration; desperation; turmoil. In the unlikely event that he has not made his point, the final minute will leave you in no doubt. And yet, in the midst of it all this, a pleading beautiful melody, begging for a cure.

(I was once advised by a piano teacher to concentrate on the left hand and the right will take care of itself. Not a chance that works here.)

This is Beethoven laid bare in the sound. Of all composers, few reach us on such a human level: he goes directly to our souls like no other. Some of Beethoven’s greatest works were written when he was completely deaf. Imagine that for a moment: to know how it’s going to sound without the experience of actually hearing it. What a genius.

I have deterred you too long. Listen to this and be glad you can. And if you haven’t had your ears syringed, you might like to consider it. I’m now turning the volume down, not up.

Just need to stop saying ‘what?’, which has become something of an irritating habit.

This article originally appeared on Nick Hely-Hutchinson’s Manuscript Notes site.

Nick Hely-Hutchinson worked in the City of London for nearly 40 years, but his great love has always been classical music. The purpose of his blog, Manuscript Notes, is to introduce classical music in an unintimidating way to people who might not obviously be disposed towards it, following a surprise reaction to an opera by his son, “Hey, dad, this is really good!“. He is married with three adult children and is a regular contributor to The Cross-Eyed Pianist.