Guest post by Anthony Hardwicke

Instrumental Music Teachers as Individual Learning Coaches

In Episode 4 of his A Land Without Music? podcast series, Julian Leeks collected lots of evidence that a musical education can benefit our children. However, he stopped short of claiming that learning a musical instrument can boost a child’s progress right across the school curriculum. I believe we can and should make this claim, and the reason is simple: when children are given piano lessons, they get weekly one-to-one coaching on how to learn.

Learning how to learn involves acquiring a key set of skills, such as planning, repetition, memorising, listening, feedback loops, etc. Once encountered, these can be deployed to help master other academic disciplines. Learning to learn has been championed in the past by academics such as Professor Guy Claxton. The main takeaway is that if we focus more on making children better learners, they can use their ‘learning muscles’ to make a success of other areas of their lives.

In a weekly one-to-one piano lesson with a peripatetic teacher, the child will experience a wide variety of different approaches to learning to play the piano. The teacher might discuss the most efficient strategies for effective practice, explain how to memorise a piece of music, talk about how music theory relates to a Mozart sonata, or they might give the student an impassioned pep-talk about how interesting and exciting Beethoven is. Perhaps they might not even intend this as an outcome, but the piano teacher might find themselves auditing that individual child’s learning skills in a way that a classroom teacher simply hasn’t got time to. I really do see the peripatetic instrumental teachers in a school as a super-motivated, highly experienced team of personal learning coaches.

What nobody talks about is how easily these useful learning approaches can be applied to learning about STEM subjects (and indeed other academic subjects). To memorise eight different chords to let you play 20 pop songs, is a very similar proposition to memorising the formulae of eight different ions so as you can work out the formulae of 20 different ionic compounds in chemistry.

Teach a child to play the piano and you will almost certainly additionally grant them regular access to an inspirational teacher who will coach them and rehearse the priceless skills they need to learn all other school subjects. In most cases, because the lessons are one-to-one, the teacher will diagnose which skills the child individually needs to develop and move forwards their ability to learn effectively.

Whether you’re a parent who wants your child to have a competitive advantage, or a politician pondering how best to invest for future society, we must have more music education.

- Read Julian Leeks’ guest post on music education

Anthony Hardwicke has been a classroom science teacher for nearly 30 years and is a dedicated amateur pianist.

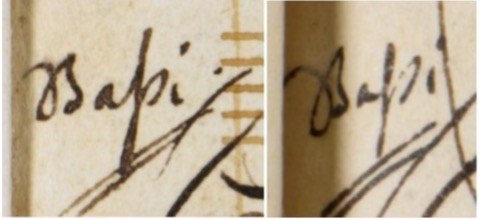

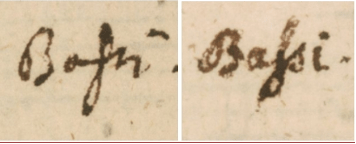

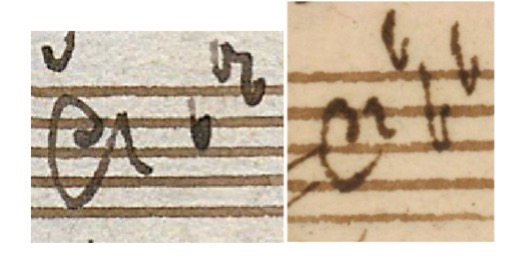

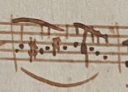

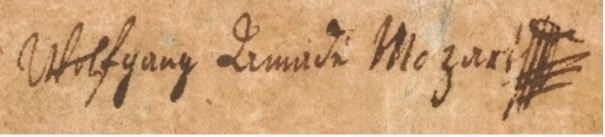

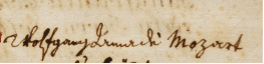

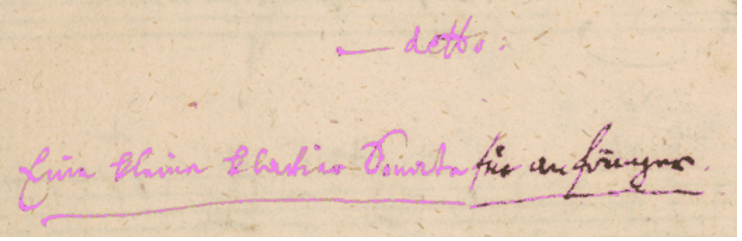

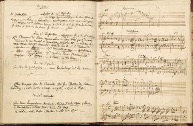

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.