Two contrasting new releases today

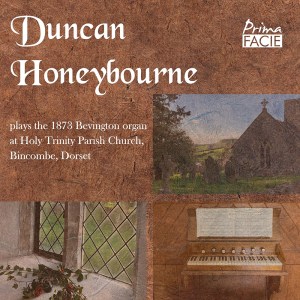

Duncan Honeybourne plays the 1873 Bevington organ at Holy Trinity parish church, Bincombe, Dorset (Prima Facie records PFCD220)

Duncan Honeybourne plays the 1873 Bevington organ at Holy Trinity parish church, Bincombe, Dorset (Prima Facie records PFCD220)

Bincombe is “a tiny place, comprising a few cottages, fields, farms and an ancient church nestled against a verdant hillside in sight of the sea. The lush meadows provide an inviting backdrop whilst, on the sightline, the English channel sparkles in the summer sunshine and shimmers mysteriously at night.” (Duncan Honeybourne). Part of the church dates from the twelfth century, with most of the remainder having been constructed in the fifteenth. The single manual organ was built by the London firm of Bevington and Sons in 1873 and supplied at a cost of £105 to the neighbouring parish of Broadwey. It was moved to Bincombe in 1903. (Bincombe is famous for its “bumps”, a cluster of round barrows which are visible from the Weymouth Relief Road.)

I was lucky enough to have a little preview of this album when Duncan gave a concert on the organ at All Saints’ church, Wyke Regis, in September. This album includes works by those masters of organ writing, Buxtehude and J S Bach, together with works by John Bull, William Byrd and Maurice Durufflé, as well as a nod to Wesssex composers, with works by Exeter-born Kate Boundy and Kate Loder of Bath. There is also a Dorset connection with Greville Cooke’s tranquil Threnody, recorded here for the first time. Cooke, a pianist, composer, poet, priest and professor at the Royal Academy, lived in north Dorset in his last years, although this piece was written during his time as Rector of Buxted, East Sussex. The album closes with John Joubert’s Short Preludes on English Hymn Tunes, composed for the new chamber organ at Peterborough Cathedral in 1990.

An enjoyable and highly varied disc which reveals the myriad colours, moods and warmth of the Bincombe organ. As a Dorset resident myself, I am particularly taken with the album’s connection to the local area near to where I live.

Songs for Our Times

Songs for Our Times

Christopher Glynn (piano), Isabelle Haile (soprano), Nick Pritchard (tenor)

Settings of lyrics by Chinwe D. John by Bernard Hughes and Stuart MacRae

(Divine Art Records DDX 21113)

I first encountered poet and lyricist Chinwe D John in spring 2022 when she contacted me about an EP of settings of her poetry (read my interview with her here).

This new release, like the previous EP, is an affirmation of Chinwe’s belief that in order to keep classical music thriving and to bring in a new audience, the work of present day composers needs to be supported. Commissioning contemporary day composers, to set music to lyrics directly reflective of our current times, is one way of accomplishing this. Chinwe herself sought out composers who shared her vision to set her words to music.

The album features two premiere recordings Kingdoms and Metropolis, whose stories will be familiar to many with their universal subjects, including the need for wisdom within the halls of power; transcendent love; an immigrant’s homesickness; the search for inner peace; all flow through the album evoking the spirit of our day and age. Despite our current turmoil, the overall tone of the album is a hopeful one, making it a welcome balm during our turbulent times.

With music by leading British composers Stuart McRae and Bernard Hughes, this is an intimate and ultimately uplifting album, with a wonderfully varied selection of very beautiful, arresting music.

Both albums are available on CD and via streaming

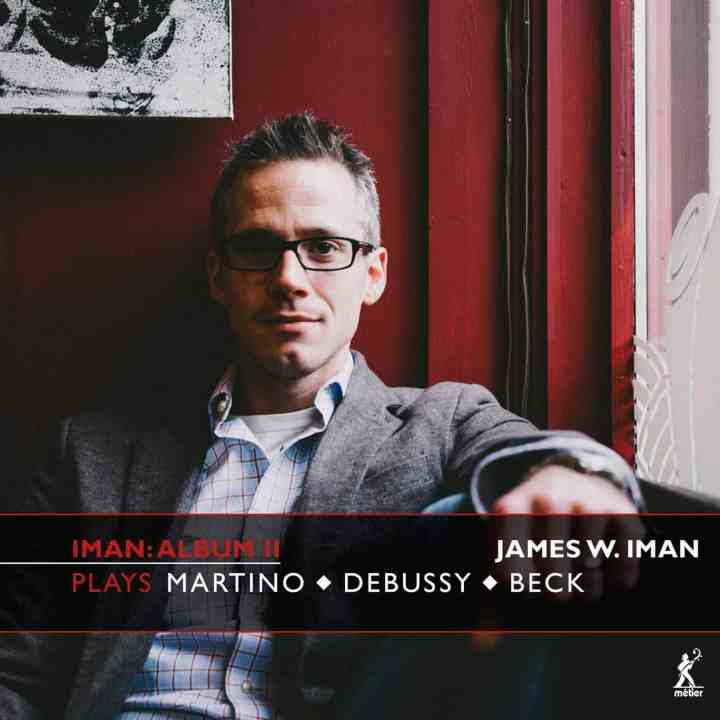

In his latest album, American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s everygreen Images alongside works by Jenny Beck and Donald Martino

In his latest album, American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s everygreen Images alongside works by Jenny Beck and Donald Martino ‘Echoes’ is the latest in Orchestra of the Swan’s ‘mixtape’ series, following on from ‘Timelapse’ and ‘Labyrinths’ (which has received over 8 million audio streams since 2021 and was shortlisted for Gramophone award in the Spatial Audio category).

‘Echoes’ is the latest in Orchestra of the Swan’s ‘mixtape’ series, following on from ‘Timelapse’ and ‘Labyrinths’ (which has received over 8 million audio streams since 2021 and was shortlisted for Gramophone award in the Spatial Audio category). Beethoven

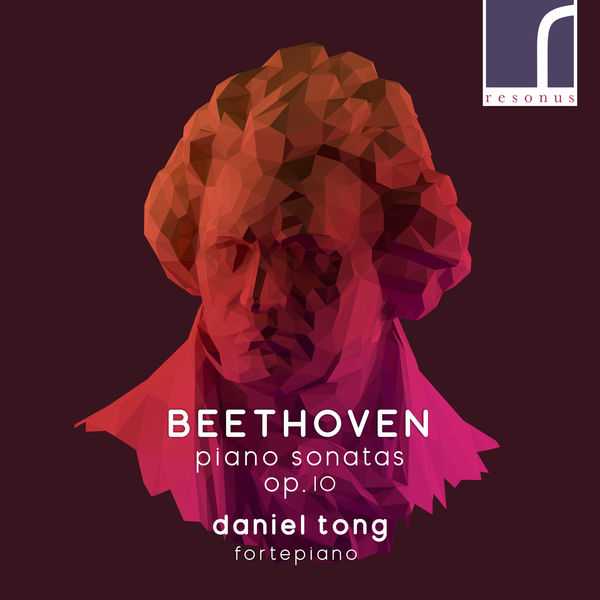

Beethoven