Guest review by Michael Johnson

It is a rare occurrence for me to slide a CD into my player and fall immediately under the spell of haunting, hypnotic music I had never heard before. But “Anima Mea” (La Musica LMU 094), performed by the Pascal Trio and the young counter-tenor Paul Figuier, did just that. I replay the full 72 minutes almost every day and have not yet tired of it.

Denis Pascal, pianist in his family trio and a leading promoter of the CD project, tells me this music “creates a space in which one can get a glimpse of another world.”

The recording marks a few important firsts. Composers Bruno Coulais and Jean-Philippe Goude created their contributions expressly for this disc, and thus can claim World First recordings. In addition, the Goude version of Gerard Leane’s Salve Regina is reworked for this recording.

Taken together, the spiritual and sacred themes, beautifully vocalized by Figuier, leave the listener transported into a poetic melancholy mood suddenly shifting to a brisk and lively piece by Arvo Pärt.

The over-all style is a unique form of minimalism. The sustained repetition is evident in the most surprising selection, “My Heart’s in the Highlands” based on the words borrowed from Scottish national poet’s work of the same name and set to the haunting music of Pärt.

Figuier renders the score in English, in a powerful but controlled high-pitched voice – long passages on a single note, backed up by the Pascal brothers and their father. The heartfelt strings and piano interpretation would leave a modern Scot an emotional wreck.

Denis Pascal has been close to Figuier since the beginning of the singer’s career. Now Pascal calls his counter-tenor performance “magnificent”, a voice with “very great expressivity”. Figuier’s growing reputation places him alongside such counter-tenors as Philippe Jarousky, Alex Luna and Andreas Scholl.

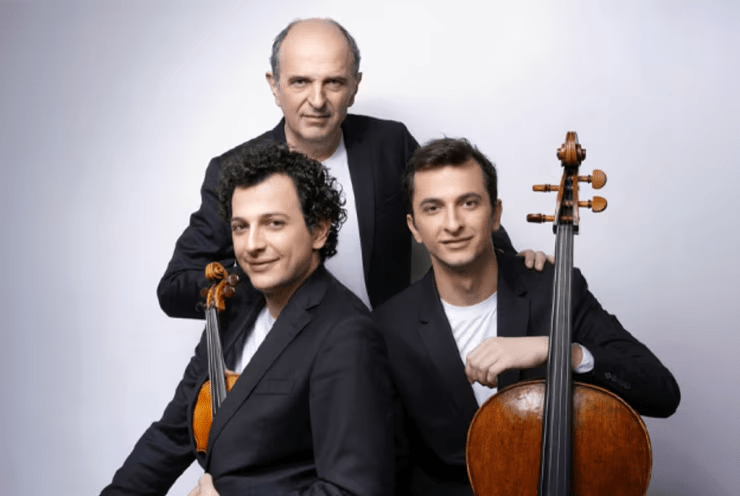

The trio comprises a rare family gathering of accomplished musicians. Pianist Denis Pascal and his two sons – violinist Alexandre and cellist Aurélien – form a unique ensemble bonded by years of common musicianship from childhood onward.

The title of the CD, “Anima Mea” (“My Soul” in English), was chosen to evoke spirituality, religious or not, evanescence, invisibility and the meaning of Salve Regina – thee traditional Magnificat in praise of the Virgin Mary, love and devotion.

An exceptionally thoughtful booklet accompanies the CD including biographies of players and composers, analysis by Yutha Tep, and the full texts in Latin, French and English.

As one French critic put it, “For anyone who loves meditative music chiseled in crystal, ‘Anima Mea’ is a stop not to be missed.”

MICHAEL JOHNSON is a music critic and writer with a particular interest in piano. He has worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Moscow, Paris and London over his journalism career. He covered European technology for Business Week for five years, and served nine years as chief editor of International Management magazine and was chief editor of the French technology weekly 01 Informatique. He also spent four years as Moscow correspondent of The Associated Press. He is a regular contributor to International Piano magazine, and is the author of five books. Michael Johnson is based in Bordeaux, France. Besides English and French he is also fluent in Russian. In 2024, he co-published with Frances Wilson ‘Lifting the Lid: Interviews with Concert Pianists’

Guest review by Adrian Ainsworth

Guest review by Adrian Ainsworth