Guest post by Luca Bianchini

Mozart is said to have written a catalogue of his works, which he reportedly began in 1784 and completed in 1791—or so it was believed until recently.

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.

All major books on Mozart, including the recently updated Köchel catalogue, which officially lists and dates his compositions, rely on this so-called autograph catalogue as a critical source. It serves to document and certify Mozart’s most important works, including, for example, the Jupiter Symphony. Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto is attributed to him precisely because it is included in this thematic catalogue, supposedly in his own handwriting.

A recent study by Professors Luca Bianchini, Anna Trombetta, and Martin Jarvis, published in the prestigious Journal of Forensic Document Examination (JFDE), introduced an innovative method of ink analysis. This study revealed that the catalogue is a forgery, fabricated around 1798 and written by multiple hands.

To verify the authenticity of a document, one must first examine the paper’s watermark. In the case of the Thematic Catalogue, no identical watermark has been found from before 1802. Furthermore, Mozart never mentioned or wrote about the catalogue during his lifetime, nor did any of his closest relatives or acquaintances. The catalogue was not included in the inventory of Mozart’s possessions compiled by court officials after his death in late 1791. In fact, there is no record of the catalogue until 1798—seven years after his death.

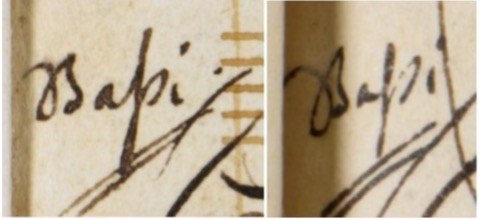

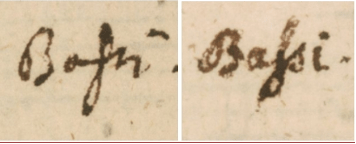

At the IGS 2023 international conference on forensic handwriting analysis, Professors Bianchini and Trombetta demonstrated, using new software developed by Bianchini in C#, that the handwriting in the catalogue does not match Mozart’s own. (For instance, consider how Mozart wrote “Bassi” in his autographs, compared with how it appears in the catalogue.)

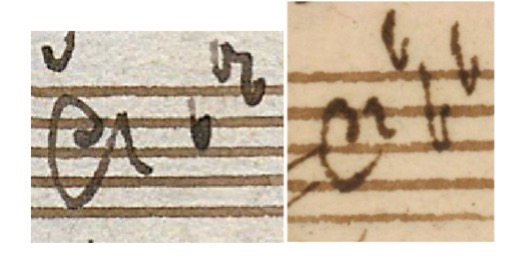

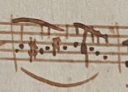

At the same conference, held at the University of Évora, Professor Anthony Jarvis presented another article, also subjected to rigorous double-blind peer review. He showed that all the bass clefs in the catalogue were not written by Mozart. If Mozart did not write the bass clefs on every stave, it is unlikely he wrote the rest of the catalogue. (Compare: on the left is an autograph, on the right the catalogue.)

Professor Heidi Harralson, a leading authority in forensic document examination, co-authored another article with Professor Martin Jarvis of Charles Darwin University in Australia, who is also an expert in the field and a Board Member of the Australia and New Zealand Forensic Science Society Northern Territory Branch. They presented evidence suggesting that Mozart could not have authored the catalogue. (For example, the regular strokes in The Marriage of Figaro autograph differ from the tremulous lines in the Thematic Catalogue, indicating copying or forgery.)

Bianchini and Trombetta had already published a book in 2018 highlighting numerous contradictions between the catalogue and Mozart’s original manuscripts.

For instance, the catalogue claims that a well-known aria was sung by the bass Albertarelli. However, it was written for the tenor Del Sole, since the higher notes would be unsuitable for a deep bass voice. Tempo markings, notes, rests, and musical themes often differ between the catalogue and the original manuscripts. Additional instruments are also listed in the catalogue, though they do not appear in the autographs.

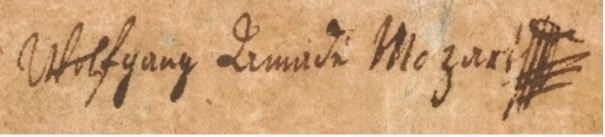

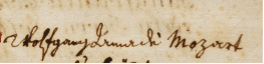

Even the signature on the cover is forged.

Signature in the catalogue:

Mozart’s verified signature (from his marriage certificate):

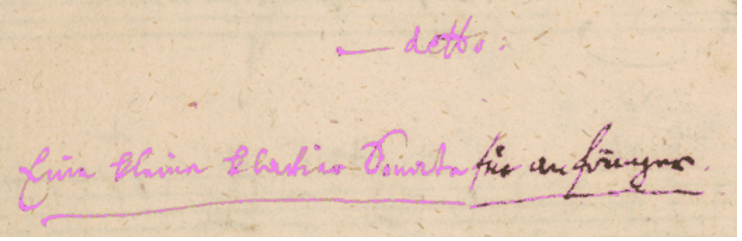

Furthermore, certain entries were added later using different inks. These discrepancies are invisible to the naked eye but become evident when computer filters are applied, as demonstrated in the recent scientific article by Bianchini, Trombetta, and Jarvis. (For instance, the initial text highlighted in pink differs in ink composition from the darker addition at the end of the line.)

It is no wonder that the musical world, especially Mozart scholars, is in turmoil. The revelation that the catalogue is a forgery challenges long-held assumptions.

For the sake of accuracy, the newly published Köchel catalogue must be revised to account for these findings. All works attributed to Mozart from 1784 to 1791 must be re-examined, as their dates and attributions have so far relied on this forged document. Given that Mozart often left his autographs unsigned and undated, the authenticity of many works is now in doubt, potentially revolutionising the history of music.

For those interested in exploring this topic further, please refer to the press release available at: https://www.mozartrazom.com/mozarts-legacy-under-scrutiny-groundbreaking-forensic-study-published/

Luca Bianchini is a musicologist from the University of Pavia, Italy, specializing in historical musicology and document analysis.