Guest interview by Michael Johnson

Guest interview by Michael Johnson

François-Frédéric Guy was just finishing his 20th performance at the piano festival of La Roque d’Anthéron in the south of France. The 2200-seat outdoor amphitheatre was almost full as Guy displayed his love of Beethoven – playing two of his greatest sonatas, No. 16 and No. 26 (“Les Adieux”). After the interval, Guy took his place at the Steinway grand again and shook up the audience with the stormy opening bars of the Hammerklavier sonata. It was like a thunderclap, as Beethoven intended. The audience sat up straight and listened in stunned silence. Monsieur Guy joined me and a colleague after his concert for a question-and-answer session about his playing, the role of the piano in his life, and his future as a conductor of Beethoven symphonies.

Question: Can you describe your technique for creating such a stormy opening for Hammerklavier? The audience was thrilled.

Answer: I try to achieve several things at once with those opening bars – signaling immediately the dimension of the complete work, its conquering majesty, and the vital energy that begins to build from those enormous, outsized chords. I try to give it weight and pace, as Beethoven wanted. It is as if Beethoven was saying, “Let’s go conquer the universe!”

Q. And your surprising low-key encore? What were you thinking?

A. I enjoy the idea behind this little piece which is probably the best-known and simplest work of Beethoven. I chose it to come immediately after the most dense and complex of Beethoven’s work, one that is relatively little known to the general public. But “Elise” is also Beethoven and can, as you say, touch people to the point of tears.

Q. What does music mean to you, as a career pianist. Since we have known each other – nearly 25 years – you have dedicated yourself entirely to music.

A. Music fills my life, my existence. Even when I am not at the instrument, even when I am speaking of other things…. Through music, one can express things that words cannot.

Q. I see you are busy – 50 concerts and recitals per year.

A. Yes, now it’s closer to 60, apportioned among concertos, chamber music and solo recitals. I try to maintain a balance of about one-third for each format.

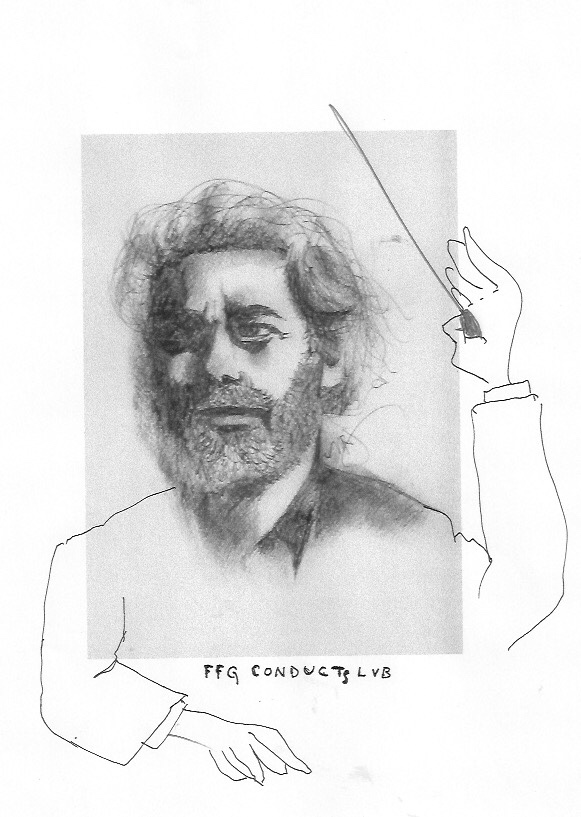

Q. Your new career seems to be taking off – now you are an orchestral conductor …

A. Yes, I am doing some conducting. I started by conducting from the keyboard, the so-called “play and conduct” format. Seven or eight years ago I started doing the Beethoven piano concertos that way, and it’s becoming more a part of my life. Now I have booked about ten play-and-conduct engagements in which I add a performance on the podium, conducting the full orchestra.

Q. Alone on the podium? What drove you to undertake this new challenge?

A. Actually it’s an old dream dating back to adolescence. I started conducting from the keyboard, and gravitated to the podium. My conducting has been well-received so I am continuing. For the moment, I conduct only Beethoven.

Q. Only the symphonies?

A. Yes, I have already done the Fourth and Fifth at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées and will conduct the Seventh in October at the Opéra de Limoges, with its very good orchestra that I have worked with frequently. I enjoy it very much, and will conduct Beethoven’s “Fidélio” there in 2022.

Q. Will you do what Rudolf Buchbiner did in Aix recently, all five piano concertos in one day?

A. Yes, I am scheduled to do just that in January, again at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées. We will start at 7 p.m. with Nos. 1 and 3, then a break, returning for Nos. 2 and 4, and finally at 10 p.m. the Fifth.

Q. This sounds like a major exploit!

A. That’s not at all why I am doing it. I merely want to take the public on a journey with me to better understand the evolution of these concertos. I find this idea very exciting and I think the public will as well. In addition, these concertos are all works of genius and so individual – each one has its own character. They do not encroach on each other. It’s like a great crossing of seas on an ocean liner. I will be taking the public with me.

Q. I was also thinking of it as a physical marathon.

A. Yes, both musically and intellectually. It’s even more true in a play-and-conduct format because I have to control what’s going on around the piano. We must remember, though, that in Beethoven’s time all concertos were performed like this. There were no conductors. Same goes for Mozart.

Q. So you are putting yourself in Beethoven’s and Mozart’s shoes, so to speak?

A. Well yes, somewhat, a bit. It’s a return to the concertos as they were intended. The piano is not king – it’s there for a dialogue with the instrumentalists, like a big family.

Q. Do you like the feeling of disappearing into the orchestra when you play-and-conduct?

A. Yes indeed. The pianist turns his or her back on the audience and is encircled by the other players. So there is a sort of fraternity – no rivalry – but it’s not easy. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. But when it does, there is a kind of unity, and that’s what is so interesting.

Q. You have said that keyboard conducting gives you a new understanding of the music. What do you mean? Does it really change your perspective?

A. Absolutely. When you play traditionally with a conductor, one must be familiar with the orchestral parts while concentrating essentially on the piano part – that’s our role. But when the pianist and the conductor are the same person, it becomes clear how completely the piano is integrated into Beethoven’s concept, and Mozart too, and then later Brahms and Schumann.

Q. How did you go about studying for your role as a conductor?

A. Well I am largely self-taught, an autodidact. But I have been counseled by some eminent conductors, notably Philippe Jordan, conductor of the Bastille Opera and soon to direct the Vienna Staatsoper, when he leaves the Bastille next year. He is a fabulous conductor, an extraordinary talent. He has helped me tremendously. And another one is Pascal Rophé, conductor of the Orchestre des Pays de Loire – Nantes and Angers. He has been a big help with the Beethoven symphonies. But I am essentially self-taught and I have no ambitions to become a full-time conductor.

Q. Ah no? That was my question – isn’t there a temptation to leave the piano behind? Solti, Bernstein and many others abandoned the piano to conduct.

A. No, no, that’s not my plan. Conducting is an extension of my interests in music. For example, I have played practically all of Beethoven’s piano music, all his chamber music, all his important piano works. And it seemed natural to try conducting. I could not imagine NOT conducting one of the symphonies. So I had to learn how to do it.

Q. Contemporary music in one of your big interests. You have collaborated with the composer Tristan Murail, I believe, and others?

A. Yes, I am currently on a concerto Tristan Murail is composing for me. What matters for me is new ideas in composition that still retain traditional structures. I want innovation, ideas that change the piano and the orchestra. Sounds we have never heard before. That’s what interests me with Tristan Murail.

Q. Are you spending your life focused solely on the piano to the exclusion of all other activities? Some pianists wear blinkers.

A. I am not wrapped up in a bubble. Nothing stops me from following important events, such as Korea, or the relations between the two Koreas.

Q. You are in touch with people outside the world of music?

A. Yes, I am very involved in astronomy, for example. I study mushrooms!

Q. Mushrooms?

A. Yes. The other day I found ten kilos of cepes on my property in the Dordogne. I have always had a passion for mushrooms of all types.

Q. John Cage was also a mushroom enthusiast. He wrote books about them. He even created the New York Mycological Society for the study of mushrooms.

A. I am a specialist too. I know all the names of different species in Latin.

Q. Tell us about your tenth Beethoven cycle planned for Tokyo. What does it consist of?

A. What it means is that I will play all of the 32 Beethoven sonatas from memory over a ten-day period, about three weekends, for the tenth time. Almost twelve hours of music.

Q. Do you have a loyal fan base in Japan?

A. Yes, yes. I usually play in a very beautiful hall in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo. Two years ago I played there with the Dresden orchestra conducted by Michael Sanderling. And last year I played all the Beethoven violin and piano sonatas there.

Q. If you give 60 recitals and concerts a year, as you said at the start of this interview, can you still find time to develop new repertoire?

A. Yes, I try to master one or two important works every year. I recently accepted to learn and play a concerto by Enescu. I always try to put aside time for new works.

Q. But at your age, don’t you find you learn more slowly?

A. Yes, I am 50 years old. But I have many things I want to do in music. I am not stopping.

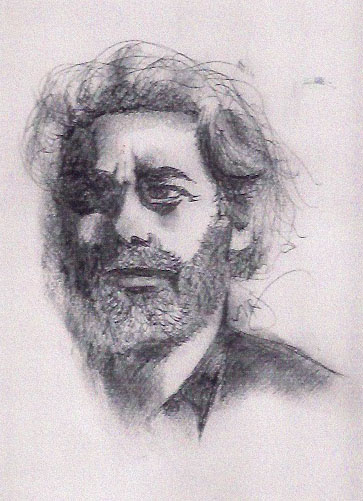

Artist portrait by Michael Johnson

Michael Johnson is a music critic with particular interest in piano. He worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Moscow, Paris and London over his writing career. He is the author of five books and divides his time between Boston and Bordeaux. He is a regular contributor to The Cross-Eyed Pianist

(This article first appeared on the Facts & Arts site. Illustrations by the author.)