Who or what inspired you to take up the piano, and pursue a career in music?

There was a wonderful piano teacher in Glasgow called Lilian Grindrod. I remember as a 5 year old watching my cousin Beth play and thinking, that looks like a lot of fun, I want to try that. My Grandpa was an organist and choral conductor and he put air under my wings at every stage of my childhood. My school was academically strong but ruthlessly anti-musical. I’m the only professional pianist I know who was never asked to play in a school concert. So all the music came through my family, where it seemed the most natural thing in the world.

Who or what have been the most important influences on your musical life and career?

When I was at Oxford, I nervously got on the London train for some lessons with Alexander Kelly. He opened my eyes to connecting emotionally with music in general, and the piano in particular. He was very generous and very funny, and lessons passed in a blur of excitement.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

Challenges change shape as careers develop. We all have demons perched on our shoulders, and the enduring challenge is to block out their noise. When I was starting out I jumped in at short notice to play for Margaret Price in Vienna. It was a hard programme with lots of songs i’d never played. No-one had pointed out that audience would be sitting on stage with me, close enough to touch. And that it was being broadcast live. I opened the music and thought, this would not be a good time to mess up.

Which performance/recordings are you most proud of?

Recording is such a bittersweet experience. I mostly hate hearing my recordings, and see only things I don’t like. Occasionally there’s a track where you might think, hmm, that was ok, but mostly my (very Scottish) reaction is to question, did I get away with it? Being what the Americans call a collaborative pianist, it usually gives me more pleasure to listen to my collaborators.

Which particular works do you think you play best?

There is a particular circle of Performers’ Hell reserved for anyone who answers that seriously! I do identify more strongly with particular areas of repertoire, and I also have a few composer allergies. But those composers come up in programmes and it’s part of my job to be convincing with them too.

How do you make your repertoire choices from season to season?

That’s a jigsaw: some programmes I choose, others land in my lap. I adore programming – it’s one of the great joys of this profession. But the choices other people make are often more interesting, and lead to musical discoveries.

Do you have a favourite concert venue to perform in and why?

I love the Crucible in Sheffield. Performing in the round with an audience raked above you is a transformative experience, particularly when that audience is warm and knowledgeable and welcoming. In a totally different way, the church at St Endellion in Cornwall is a place where magic happens, for reasons I’ve never fully understood.

What is your most memorable concert experience?

I did a recital in Japan where every time I nodded for the page turner to turn, she slowly nodded back, transforming the gesture into a most elegant bow. Every time. I had to anticipate by half a line to keep the show on the road.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

I’d love to come up with something highbrow and philosophical, but the honest truth is, getting by without major disaster. Actually enjoying the process is the Holy Grail.

What do you consider to be the most important ideas and concepts to impart to aspiring musicians?

Be true to the composer, and to yourself. In that order. Remember that a large part of talent is the capacity to change.

What is your present state of mind?

There’s not a pianist alive whose state of mind is anything other than “I Really Should Be Practising”.

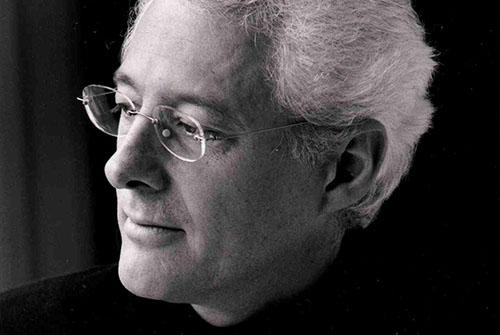

Iain Burnside is a pianist who has appeared in recital with many of the world’s leading singers (“pretty much ideal” BBC Music Magazine). He is also an insightful programmer with an instinct for the telling juxtaposition. His recordings straddle an exuberantly eclectic repertoire ranging from Beethoven and Schubert to the cutting edge, as in the Gramophone Award-winning NMC Songbook. Recent recordings include the complete Rachmaninov songs (Delphian) with seven outstanding Russian artists (“the results are electrifying” Daily Telegraph). Burnside’s passion for English Song is reflected in acclaimed CDs of Britten, Finzi, Ireland, Butterworth and Vaughan Williams, many with baritone Roderick Williams.

Away from the piano Burnside is active as a writer and broadcaster. As presenter of BBC R3’s Voices he won a Sony Radio Award. For Guildhall School of Music & Drama Burnside has devised a number of singular theatre pieces. A Soldier and a Maker, based on the life of Ivor Gurney, was performed at the Barbican Centre and the Cheltenham Festival, and later broadcast by BBC R3 on Armistice Day. His new project Swansong has been premiered at the Kilkenny Festival and will play in Milton Court in November.

Future highlights include performances of the three Schubert songcycles with Roderick Williams at Wigmore Hall. A Delphian release of songs by Nikolai Medtner launches a major series of Russian Song in the 2018 Wigmore Hall season. Other forthcoming projects feature Ailish Tynan, Rosa Feola, Andrew Watts, Robin Tritschler and Benjamin Appl.

Iain Burnside is Artistic Director of the Ludlow English Song Weekend and Artistic Consultant to Grange Park Opera.

(Artist photo and biography courtesy of Askonas Holt)