Of What Is, and What Pretends to Be

Howard Smith

#note4notethebook

Amateur pianist and author of Note For Note – Bewitched, Bothered & Bewildered, Howard Smith, recently trained an artificial intelligence (AI) to think and write as Erik Satie. Using a custom GPT, Howard generated a series of beautiful images of the composer together with imagined statements, quotations and poetry based on his life, work and ethos and that of other artistic movements of the era, including Dada. The resultant images were used in a ‘moving art’ exhibit during a performance of Satie’s iconic music at an piano recital given by Howard at the October Gallery, London, in April of this year. Satie’s imagined musings were given to everyone who attended the evening in the form of a small ‘take home’ booklet.

To celebrate the life and work of this enigmatic and endlessly intriguing figure, on this the centenary of his death (1st July 1925), we are sharing Howard’s remarkable AI gaze into the mind of the genius.

“I do not compose music as one builds a cathedral, grand and towering. No, my music is a chair—simple, functional, meant to be sat upon, or ignored entirely. It does not seek to impress but to exist, to hover in the air like a thought half-formed, like a joke no one quite understands. I reject the pomposity of symphonies, the tyranny of tradition. Instead, I write in the language of absinthe and rain, of lost gloves and distant laughter. If my music confuses you, good. If it makes you smile at nothing in particular, even better. It is not there to be understood—it is there to be.”

My dear friends, let me regale you with tales of my musical endeavours. I, Erik Satie, have always been drawn to the unconventional, the unorthodox, the nonsensical, and the illogical. I have sought both to challenge and to mock the status quo, to push and to shatter the boundaries of what is considered to be “music.”

The movement of Impressionism, with its emphasis on light and color, has had a profound influence on my compositions. I strive to evoke a sense of atmosphere and mood, chaos and confusion, through the use of harmonic and melodic colour—sometimes nonsensical, sometimes dissonant, always daring. Unconventional harmonies and dissonant chord progressions are my allies in creating a sense of tension, disorder, and delight. As I have often mused, “I have found it necessary to get rid of all the parts that everyone likes and keep all those which no one likes—and perhaps also those which make no sense.”

The cabaret and café-concert culture of my beloved Paris has also been a tremendous source of inspiration. The playful, irreverent, satirical, and nonsensical spirit of these performances echoes in my compositions. I have woven elements of cabaret into my music, always seeking to push and mock the boundaries of acceptability. As I have whimsically declared, “I am a country whose boundaries are the imagination, and perhaps, absurdity.”

I have also been shaped by the simplicity and repetition found in folk music, medieval and Renaissance music, and popular music. These have all been crucial in my quest to evoke hypnotic and meditative states, as well as chaotic and illogical ones. My compositions, described by some as “inventive and original,” by others as “nonsensical and illogical,” are my proudest achievements.

My unique and unconventional style has left a mark on the composers who have followed me. The repetitive rhythms and simple harmonies that I have embraced have seeped into the minimalist and Dada styles alike. My music has also been a curious influence on the development of ambient, chaotic, and experimental music.

Friends, my music is the product of a wide and wild range of influences and genres. I have always sought to challenge and mock the status quo, to both push and shatter the boundaries of “music.” And I shall continue to do so, for as I have said, “The essential thing is to invent,” whether it be sense or absurdity. And with that, I bid you adieu, and hope that you will enjoy my compositions—whatever they may be.

The composer speaks of the work of others!

“You ask me of others? … Ah, Schoenberg—he has built a magnificent prison for sound, where no note may escape without permission. And Webern! His music is like watching a flea conduct an orchestra—so precise, so delicate, and yet, one wonders if it is there at all. As for Berg, well, he writes like a man composing letters to ghosts, beautifully tragic, but I fear the ghosts do not read music. You see, these gentlemen have taken ‘melody’ out for a long walk and forgotten to bring it home. I prefer music that winks at you from across the room, rather than staring at you sternly from a lectern.”

Advice for those who foolishly choose to play my music

In the realm of my melodies, a curious plight befalls, The challenges that unfold when my music enthralls. Performing my compositions, a task not for the faint, For they dance in a world where conventions are taint.

The tempo, a riddle that defies the clock’s hand, Floating in ambiguous rhythms, like shifting sand. One must navigate the maze of pauses and beats, And embrace the uncertainty where dissonance meets.

Oh, the dynamics, a game of whispers and roars, They whisper secrets and tales, then loudly encore. From the softest of whispers to the loudest of cries, Unveiling the emotional depths hidden in disguise.

The elusive nuances, delicate and refined, Each note a story, a journey entwined. One must master the art of subtlety and grace, To capture the essence of each fleeting embrace.

And let us not forget the quirky, unexpected turns, Where surprises abound and convention adjourns. For in the realm of my music, the unexpected thrives, As rules and expectations take nosedives.

So, dear performers, embrace the challenge, be bold, Unleash the spirit of my compositions, untold. For within the difficulties lie treasures untamed, In the realm of my music, true art is claimed.

Perform my works with passion, with heart aflame, Navigate the obstacles, conquer the untamed. And in the triumph of each difficult refrain, You’ll unlock the essence of my musical terrain.

So, to those who dare to venture on this path, May your performance ignite the eternal Satie wrath. For in the difficulties lie the seeds of triumph and grace, In the performance of my music, a journey takes place.

“The notes danced on the page

With no care for time or age

They sang of chaos and confusion

In a melody of self-illusion

The harmony was out of tune

But that only added to the moon

The rhythm was a mess

But it was the best.

For in this madness, we find art

In this chaos, a brand new start.

So let us revel in the absurd

For it is in this, true beauty is heard.”

Of What Is, and What Pretends to Be

Erik Satie was known for his sharp wit and his often unusual, provocative comments. Below are quotations attributed to him:

“I took to my room and let small things evolve slowly.”

“Before I compose a piece, I walk around it several times, accompanied by myself.”

“I have never written a note I didn’t mean.”

“Artists of my kind deal with matters of the heart; they have no time to bother about digestion.”

“The musician is perhaps the most modest of animals, but he is also the proudest.”

“I am by far your superior, but my notorious modesty prevents me from saying so.”

“What I am trying to achieve is a new way of approaching old sentimental airs.”

“When I was young, they told me: ‘You’ll see when you’re fifty.’ I’m fifty. I’ve seen nothing.”

“An artist must organize his life. Here is the exact timetable of my daily activities:

I rise at 7:18; am inspired from 10:23 to 11:47. I lunch at 12:11 and leave the table at 12:14. A healthy ride on horse-back round my domain follows from 1:19 pm to 2:53 pm. Another bout of inspiration from 3:12 to 4:07 pm. From 5 to 6:47 pm various occupations (fencing, reflection, immobility, visits, contemplation, dexterity, natation, etc.)”

“I write poetry because my furniture refuses to listen to my piano sonatas, and someone must suffer the metaphors.”

In the Key of Silence

I walk alone in silent streets,

Where echoes dance on muted feet,

A solitary waltz of sound,

In the spaces where I am found.

My fingers trace the ivory’s curve,

In notes that neither rise nor swerve,

But drift like smoke, like gentle rain,

In melodies that speak of pain.

I dream of chords that never clash,

Of gentle waves that softly splash,

Against the shores of time and thought,

In patterns that I never sought.

My music breathes in shadows dim,

A whisper on the twilight’s rim,

A gentle sigh, a fleeting breath,

That lingers on the lips of death.

I am a ghost within a tune,

A faint lament beneath the moon,

A passing breeze, a flickering flame,

That burns without a name or fame.

Yet in these notes, my soul resides,

A truth that every silence hides,

For I am more than flesh and bone,

In every sound, I find my home.

So let the world in chaos spin,

I’ll find my peace where notes begin,

In simple strains, in quiet air,

My music lives, forever there.

I Dance with Notes Like Drunken Clocks

I watch the notes dance on the page, wild and free,

They waltz with teacups, and swim in tea,

Time means nothing, age even less,

I’m the maestro of madness, I must confess.

I sing of chaos in colors unseen,

A symphony woven from my strangest dream,

Where clocks melt and cows take flight,

In a melody plucked from the dead of night.

Harmony grins with a twisted face,

Out of tune, yet perfectly misplaced,

I let it tangle with the stars above,

Skipping beats like a broken love.

The rhythm, oh, what a beautiful mess!

A riot of tick-tocks in a disorderly dress,

I send it stumbling down a rabbit hole,

Where the absurd is king, and I am whole.

For in this madness, I craft my art,

A canvas of whispers, a Dadaist heart,

With scissors and glue, I piece it together,

A collage of sound, indifferent to weather.

In chaos, I find my brand new start,

A genesis born from an unchained heart,

So I revel in the absurd’s sweet kiss,

Knowing in this cacophony, true beauty exists.

The notes are my clocks, my clocks are dreams,

And nothing is ever as it seems,

In my world of topsy-turvy glee,

I dance with the notes, I dance with me.

Let the pigeons wear hats, the fish recite,

I’ll bring out the sun in the dead of night,

For in this nonsense, my truth is heard,

A symphony of the absurd, every note absurd.

So I play on, my friends, in this grand charade,

In the music of life, let my madness parade,

For in my dissonance, true art’s concealed,

In my dance with the absurd, all beauty’s revealed.

“I do not write music to please the ear; I write to tease the mind, to make it dance in absurdity. My melodies are like lost children—wandering through the night, searching for a place that does not exist.”

“Life is a series of dissonant notes, beautifully out of tune. And in that, we find our harmony. To create is to embrace the absurd, to revel in the nonsensical, and to find order in the delightful chaos of the mind.”

“Time is an illusion, and my music is its shadow, fleeting and ever-changing, yet always there. I compose not for applause, but for the invisible conversations between the notes and the silence.”

“The true art lies not in perfection, but in the daring to be imperfect—a melody that dares to trip over itself.”

“In every absurdity, there is a truth waiting to be heard, a beauty that defies the ordinary. My music does not follow the rules of time; it dances to the rhythm of dreams, where clocks have no hands.”

“I live in a world where pianos converse with teapots, and where every note is a secret shared between the absurd and the sublime.”

“Very finally, with a hint of silence.”

Attribution? This curious little booklet—filled with poetry, musings, and the ever-enigmatic words of composer Erik Satie—was conjured into being by Howard Smith and “Erik Satie”, with a generous helping of GPT-4 magic. Artwork projected during Personal Passions @ October Gallery was created with the assistance of MidJourney and DALL-E. Questions to smithhn@gmail.com

Piano Notes, The Hidden World of the Pianist, by Charles Rosen (first published in the USA by The Free Press in 2002., republished by Penguin in 2004).

Piano Notes, The Hidden World of the Pianist, by Charles Rosen (first published in the USA by The Free Press in 2002., republished by Penguin in 2004). Piano Lessons, Music, Love & True Adventures, by Noah Adams. Published in 1997 (Delta/Random House), the book explores why a fifty one-year old man would suddenly decide he has to own a grand piano: a Steinway. Adams, a radio journalist and host of NPR’s flagship news program All Things Considered, sets out a month-by-month chronicle of one year spent pursuing his passion for the piano. The book is packed with anecdotes beyond the telling of his own story of obsession, covering such diverse worlds as Bach, Pop, boogie-woogie, and is littered with his recollection of meeting with or speaking to masters such as Glenn Gould, Leon Fleisher and George Shearing. Adams is a consummate writer, and as each month and season in his year long journey spins by, culminating in his surprise ‘Christmas Party performance’ of Schumann’s Traumerei from Scenes from Childhood, he reflects on what could have been. ‘There’s been a secret, hiding in my heart about this piano-learning endeavor: Perhaps I do have a talent and no one knows.’ Adam’s dedication is ‘For all who would play’. Written by an amateur pianist who sets himself on a path to master the piano, this book is an engaging, entertaining and inspiring read whose sentiments will resonate with others on a similar journey.

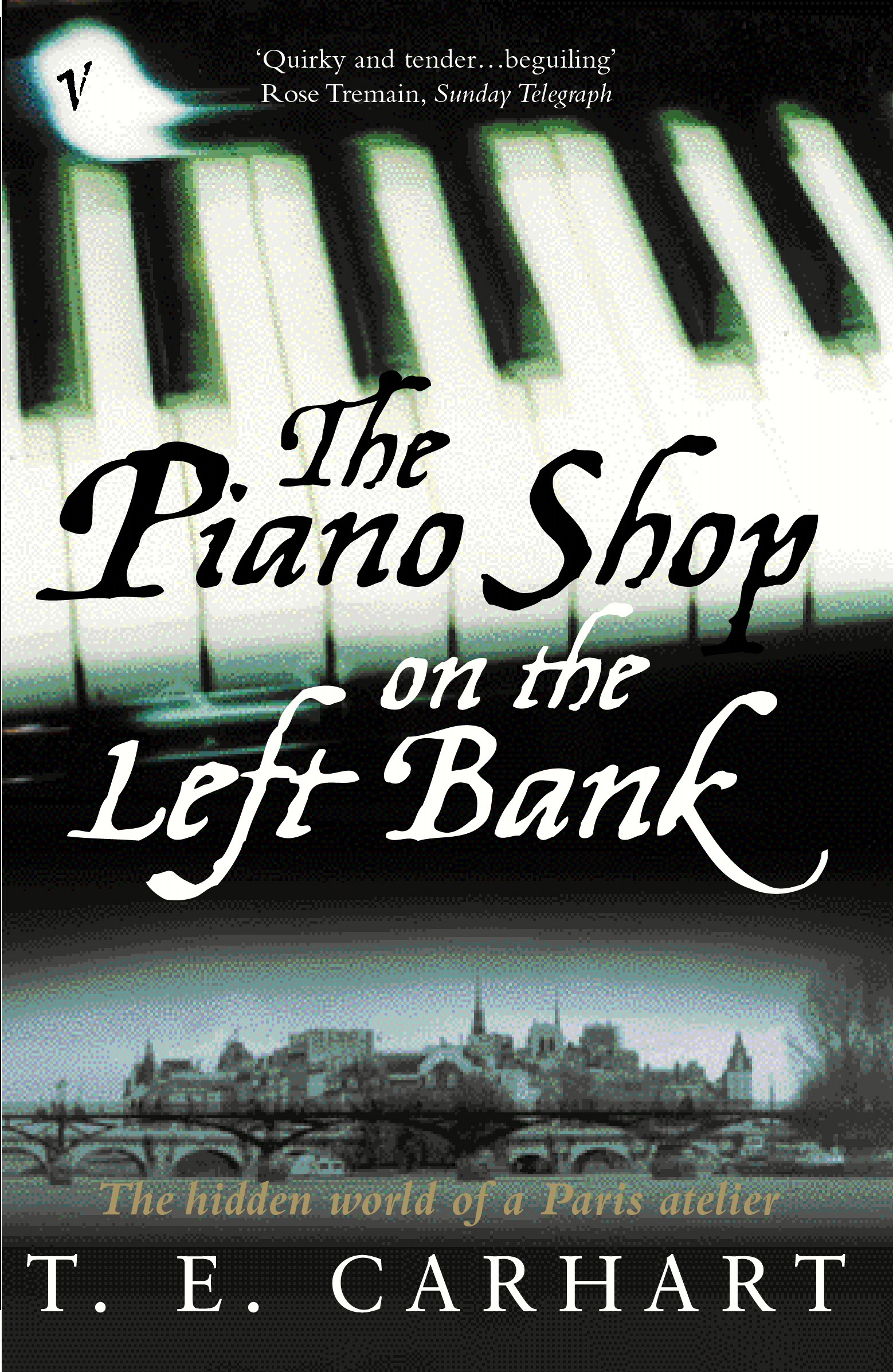

Piano Lessons, Music, Love & True Adventures, by Noah Adams. Published in 1997 (Delta/Random House), the book explores why a fifty one-year old man would suddenly decide he has to own a grand piano: a Steinway. Adams, a radio journalist and host of NPR’s flagship news program All Things Considered, sets out a month-by-month chronicle of one year spent pursuing his passion for the piano. The book is packed with anecdotes beyond the telling of his own story of obsession, covering such diverse worlds as Bach, Pop, boogie-woogie, and is littered with his recollection of meeting with or speaking to masters such as Glenn Gould, Leon Fleisher and George Shearing. Adams is a consummate writer, and as each month and season in his year long journey spins by, culminating in his surprise ‘Christmas Party performance’ of Schumann’s Traumerei from Scenes from Childhood, he reflects on what could have been. ‘There’s been a secret, hiding in my heart about this piano-learning endeavor: Perhaps I do have a talent and no one knows.’ Adam’s dedication is ‘For all who would play’. Written by an amateur pianist who sets himself on a path to master the piano, this book is an engaging, entertaining and inspiring read whose sentiments will resonate with others on a similar journey. The Piano Shop on the Left Bank, Discovering a Forgotten Passion in a Paris Atelier, by Thad Carhart, became a New York Times Bestseller. First published in 2001 the book tells the story of how, while walking his children to school, the author chances upon an unassuming piano workshop in his Paris neighbourhood. Curious, he eventually wins the trust of the owner and is gradually introduced to the complexities of the engineering of pianos old and new, as well as the curiosities of the unique style of ‘trade’ in pianos between dealers, professionals and amateurs who wish to acquire distinctive and beautiful instruments. Along the way we learn much of the rich history and art of the piano, and the stories of those special people who care for them.

The Piano Shop on the Left Bank, Discovering a Forgotten Passion in a Paris Atelier, by Thad Carhart, became a New York Times Bestseller. First published in 2001 the book tells the story of how, while walking his children to school, the author chances upon an unassuming piano workshop in his Paris neighbourhood. Curious, he eventually wins the trust of the owner and is gradually introduced to the complexities of the engineering of pianos old and new, as well as the curiosities of the unique style of ‘trade’ in pianos between dealers, professionals and amateurs who wish to acquire distinctive and beautiful instruments. Along the way we learn much of the rich history and art of the piano, and the stories of those special people who care for them. Piano Pieces, by Russell Sherman. Described by The New Yorker as ‘Startling … dreamily linked observations about the experience of piano playing and a thousand other unexpected subjects’. Sherman’s book is cerebral, esoteric and at times philosophical in its ruminations on the physical, metaphysical and emotional activity of playing the piano and being a pianist. It is packed with profound ponderings and thought-provoking insights, and although it is written by a professional pianist, it is relevant to anyone who plays and/or teaches the piano. For example, on coordination he says: ‘Coordination is what the teacher must begin and end with. As I stand next to my student I feel dangerously like a puppeteer trying to guide him or her through the vortex of ideas and feelings. I console myself in the realization that eventually students will internalise this role and learn to master their own fate’. In another ‘thought’ he simply writes: ‘When one plays Beethoven one must serve Beethoven. No, one must represent Beethoven. No, one must be Beethoven’. An unusual contemplation on the piano and what it means to “be” a pianist.

Piano Pieces, by Russell Sherman. Described by The New Yorker as ‘Startling … dreamily linked observations about the experience of piano playing and a thousand other unexpected subjects’. Sherman’s book is cerebral, esoteric and at times philosophical in its ruminations on the physical, metaphysical and emotional activity of playing the piano and being a pianist. It is packed with profound ponderings and thought-provoking insights, and although it is written by a professional pianist, it is relevant to anyone who plays and/or teaches the piano. For example, on coordination he says: ‘Coordination is what the teacher must begin and end with. As I stand next to my student I feel dangerously like a puppeteer trying to guide him or her through the vortex of ideas and feelings. I console myself in the realization that eventually students will internalise this role and learn to master their own fate’. In another ‘thought’ he simply writes: ‘When one plays Beethoven one must serve Beethoven. No, one must represent Beethoven. No, one must be Beethoven’. An unusual contemplation on the piano and what it means to “be” a pianist. Play It Again, An Amateur Against The Impossible, by Alan Rusbridger, is almost certainly the most well-known of the books in this niche genre. In 2010, the then editor of the Guardian newspaper, set himself an ‘almost impossible’ task: to learn, in the space of a year, Chopin’s Ballade No. 1, considered one of the most difficult pieces in the repertoire that inspires dread in many professional pianists. Written in the form of diary extracts, the book charts not only his adventures with the Ballade, a project he likens to George Mallory attempting to climb Everest “in tweed jacket and puttees”, but also an extraordinarily busy year for his newspaper (The Guardian) and the world in general: the year of the Arab Spring and the Japanese Tsunami, Wikileaks and the UK summer riots, and the phone hacking scandal and subsequent Leveson Enquiry. Despite this, somehow the author managed to find ‘twenty minutes practice a day’ – even if it meant practising in a Libyan hotel in the middle of a revolution. Much of the book is a glimpse into Alan Rusbridger’s “practice diary”, his day-to-day responses to learning the piece. For the serious amateur pianist and teacher, Rusbridger’s analysis, virtually bar-by-bar, is very informative, but you would want to have a copy of the score beside you as you read. There is also plenty of useful material on how to practice “properly” – something Rusbridger has to learn almost from scratch, with the guidance of, amongst others, eminent pianists such as Murray Perahia and Lucy Parham – and how to make the most of limited practice time. Alongside this, we also meet piano restorers and technicians to peer into the rarefied world of high class grand pianos (Steinway, Fazioli), as well as neurologists (with whom Rusbridger discusses the phenomenon of memory), piano teachers, pianists all over the world who have played or are studying the piece, other journalists, celebrities, politicians, dissenters, and Rusbridger’s friends and family.

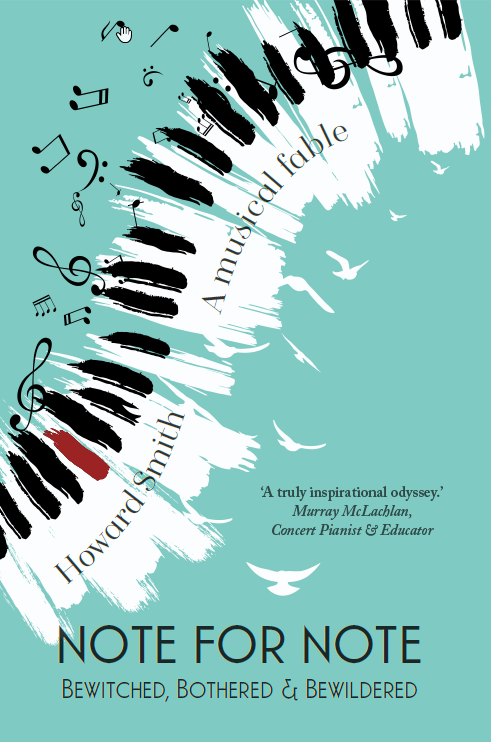

Play It Again, An Amateur Against The Impossible, by Alan Rusbridger, is almost certainly the most well-known of the books in this niche genre. In 2010, the then editor of the Guardian newspaper, set himself an ‘almost impossible’ task: to learn, in the space of a year, Chopin’s Ballade No. 1, considered one of the most difficult pieces in the repertoire that inspires dread in many professional pianists. Written in the form of diary extracts, the book charts not only his adventures with the Ballade, a project he likens to George Mallory attempting to climb Everest “in tweed jacket and puttees”, but also an extraordinarily busy year for his newspaper (The Guardian) and the world in general: the year of the Arab Spring and the Japanese Tsunami, Wikileaks and the UK summer riots, and the phone hacking scandal and subsequent Leveson Enquiry. Despite this, somehow the author managed to find ‘twenty minutes practice a day’ – even if it meant practising in a Libyan hotel in the middle of a revolution. Much of the book is a glimpse into Alan Rusbridger’s “practice diary”, his day-to-day responses to learning the piece. For the serious amateur pianist and teacher, Rusbridger’s analysis, virtually bar-by-bar, is very informative, but you would want to have a copy of the score beside you as you read. There is also plenty of useful material on how to practice “properly” – something Rusbridger has to learn almost from scratch, with the guidance of, amongst others, eminent pianists such as Murray Perahia and Lucy Parham – and how to make the most of limited practice time. Alongside this, we also meet piano restorers and technicians to peer into the rarefied world of high class grand pianos (Steinway, Fazioli), as well as neurologists (with whom Rusbridger discusses the phenomenon of memory), piano teachers, pianists all over the world who have played or are studying the piece, other journalists, celebrities, politicians, dissenters, and Rusbridger’s friends and family. And so we come to the new kid on the block: Howard Smith’s Note For Note, Bewitched, Bothered & Bewildered. Released in 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, Smith’s book was described by amateur pianist and performing arts clinician Marie McKavanagh as, ‘A brutally honest personal testimony of a human experience that enriches life via the intimate physical act of working with a musical instrument.’ Over thirty-eight chapters, covering a period of just three years, Smith charts his unexpected transformation from software-geek to musician or, as he points it ‘from the digital to the analogue: from the bits and bytes of the computer industry to the world of melody, harmony and musical performance’. Covering topics as diverse as lead sheets, mental performance, unblocking, the musical ‘fourth’, the circle of fifths, two-five-one progressions, modes and chord-scale theory, theory and practice is blended with what Victoria Williams of MyMusicTheory called ‘captivating story-telling’. The result is a unique memoir and simultaneously an educational text for all amateur pianists, described by educator Andrew Eales (who blogs as Pianodao) as ‘Essential reading for 2021’. However, Note For Note is not a textbook; nor is it a novel. Smith calls it a ‘musical fable’; a message as much about how not to go about learning the piano as it is a guide to best practice. The author claims that every word is true, and I have no reason to doubt him. In the song-writing chapters, for example, Smith enumerates the process of his work with his teachers in composition and lyric-writing, presenting every chord symbol and poetic line as it happened. (One day, he tells me, he will release this music.) Smith’s story (and writing) unfolds as it happened, or as he says, ‘from the theory to the practice’. Devoid of any artifice, perhaps the most surprising aspect of this book is depth of wisdom it embodies for someone who, at the time of writing, had only been playing for a couple of years. We learn that Smith is the proverbial ‘late returning’ amateur, and this reality (and his narrowing ‘window of opportunity’) weighs heavily on him at key points in the text. He returned to the piano, leaving the IT career he loved, after a ‘gap’ of forty-five years, having only achieved a modest ‘grade three’ as a child; a child engineer who found the mechanism of the piano and its ‘physics of sound’ more interesting than any disciplined ‘practice’. Note For Note is a book written by an amateur pianist for amateur pianists, especially those, like Smith, who struggle to make the transition from ‘intermediate’ to ‘advanced’. The author does eventually learn what it means to ‘be a musician’, and you believe him: concert pianist Murray McLachlan, Head of Keyboard at Chetham’s School of Music, called it a ‘A truly inspirational odyssey’. As to how the book came to be written, that must remain strictly ‘no spoilers’.

And so we come to the new kid on the block: Howard Smith’s Note For Note, Bewitched, Bothered & Bewildered. Released in 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, Smith’s book was described by amateur pianist and performing arts clinician Marie McKavanagh as, ‘A brutally honest personal testimony of a human experience that enriches life via the intimate physical act of working with a musical instrument.’ Over thirty-eight chapters, covering a period of just three years, Smith charts his unexpected transformation from software-geek to musician or, as he points it ‘from the digital to the analogue: from the bits and bytes of the computer industry to the world of melody, harmony and musical performance’. Covering topics as diverse as lead sheets, mental performance, unblocking, the musical ‘fourth’, the circle of fifths, two-five-one progressions, modes and chord-scale theory, theory and practice is blended with what Victoria Williams of MyMusicTheory called ‘captivating story-telling’. The result is a unique memoir and simultaneously an educational text for all amateur pianists, described by educator Andrew Eales (who blogs as Pianodao) as ‘Essential reading for 2021’. However, Note For Note is not a textbook; nor is it a novel. Smith calls it a ‘musical fable’; a message as much about how not to go about learning the piano as it is a guide to best practice. The author claims that every word is true, and I have no reason to doubt him. In the song-writing chapters, for example, Smith enumerates the process of his work with his teachers in composition and lyric-writing, presenting every chord symbol and poetic line as it happened. (One day, he tells me, he will release this music.) Smith’s story (and writing) unfolds as it happened, or as he says, ‘from the theory to the practice’. Devoid of any artifice, perhaps the most surprising aspect of this book is depth of wisdom it embodies for someone who, at the time of writing, had only been playing for a couple of years. We learn that Smith is the proverbial ‘late returning’ amateur, and this reality (and his narrowing ‘window of opportunity’) weighs heavily on him at key points in the text. He returned to the piano, leaving the IT career he loved, after a ‘gap’ of forty-five years, having only achieved a modest ‘grade three’ as a child; a child engineer who found the mechanism of the piano and its ‘physics of sound’ more interesting than any disciplined ‘practice’. Note For Note is a book written by an amateur pianist for amateur pianists, especially those, like Smith, who struggle to make the transition from ‘intermediate’ to ‘advanced’. The author does eventually learn what it means to ‘be a musician’, and you believe him: concert pianist Murray McLachlan, Head of Keyboard at Chetham’s School of Music, called it a ‘A truly inspirational odyssey’. As to how the book came to be written, that must remain strictly ‘no spoilers’.