Last week I went up to Hertford, the attractive county town of Hertfordshire, to attend an inaugural concert and reception, ahead of this year’s Hertfordshire Festival of Music (HFoM) which runs from 7 to 14 June.

I have been involved in the Festival since its founding by conductor Tom Hammond (who tragically died in 2021) and composer James Francis Brown, initially in an ad hoc way by sharing details of the festival here and on my social networks, and since 2020 as the Festival’s publicist.

Now in its ninth year, the festival has grown from a weekend to a full week of concerts and related events/activities. The ethos and aims of the festival have remained largely the same – presenting world class classical music and musicians in the heart of Hertfordshire alongside education and outreach projects within the local community – and each year sees a different Principal Artist (Emma Johnson, Ben Goldscheider, Steven Isserlis and Stephen Hough to name a few) and Featured Living Composer (e.g. Judith Weir, CBE, David Matthews), as well as musicians who live and/or come from Hertfordshire (flautist Emma Halnan, pianist Florian Mitrea). The concert programmes are varied and imaginative, and the range of artists is impressive. Previous performers/ensembles have included ZRI, the Rosetti Ensemble, pianists Katya Apekisheva and Charles Owen, violinists Litsa Tunnah, Mathilde Milwidsky and Chloe Hanslip, cellist Guy Johnson, and guitarist Jack Hancher.

Potential audiences (and reviewers) who live in London are often reluctant to journey too far out of the metropolis to experience live music (it was via an online discussion about this issue that I first met Tom Hammond, back in 2015), yet the ease with which one can travel to Hertfordshire was quite evident when, after having lunch with my father near Kings Cross, I took the Circle Line a few stops to Moorgate and thence a train to Hertford North station (Hertford has 2 railway stations; trains from Hertford East go to Liverpool Street). The journey was less than an hour, comfortable and pleasant, and my hotel was an easy 10-minute stroll from the station to the attractive historic centre of town. Hertford is also easily accessible by road, again less than an hour’s drive from London.

HFoM concerts take place in the town’s two main churches, St Andrew’s and All Saints, both of which are within walking distance of the town centre. Other events take place at the Hertford Quaker Meeting House (the oldest meeting house built by Friends that has remained in unbroken use since 1670), and other local venues.

If you were to make a mini break or weekend visit to Hertford, or even just a day trip, you’ll find the town has a good range of independent shops, cafes, restaurants and pubs. Ahead of the evening event, I enjoyed a stroll around the town in unexpectedly mild sunshine.

This year’s festival runs from 7 to 14 June. I can’t reveal the full programme yet but I can tell you that this year’s Festival theme, ‘Shadows to Light: Musical Journeys in Conflicts and Peace’, which celebrates the universal language of music through times of adversity and peace, and touches on the 80th anniversary of VE Day alongside contemporary global conflicts. From young musicians to established international artists, jazz music, the Hertford Community Concert Band, and even a special Festival Church Service, this year’s Festival offers something for everyone and features over 30 events across music and outreach activities, of which 50% are free, with concessions applied to ticketed events.

You can enjoy early access to Festival news by signing up to the HFoM newsletter or by following the festival on social media.

Hertfordshire Festival of Music website

Hertfordshire Festival of Music is built on the involvement, support and encouragement of Hertford and the county’s communities who help build a thriving and rich Festival for the communities HFoM wishes to serve.

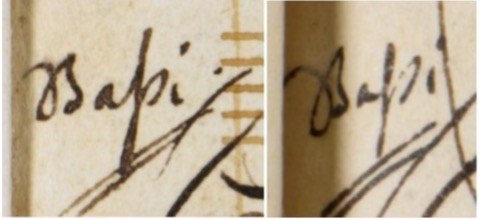

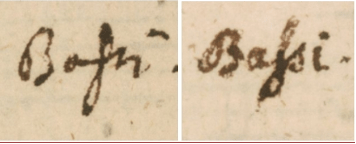

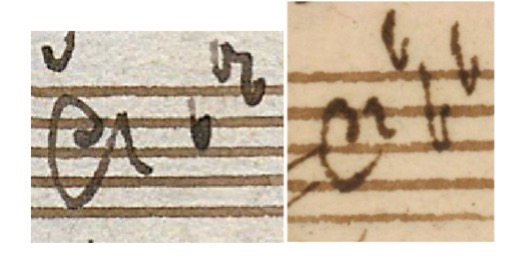

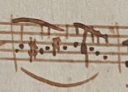

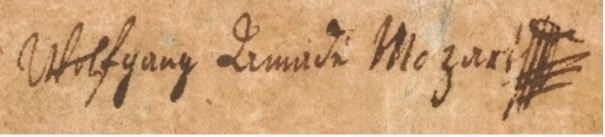

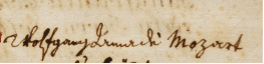

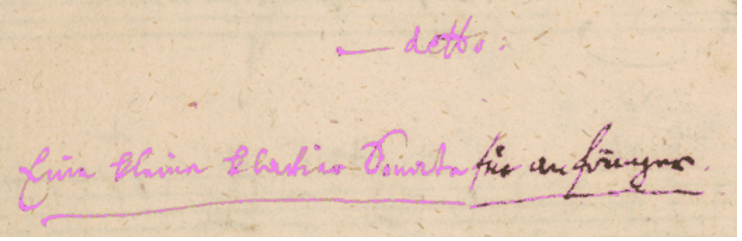

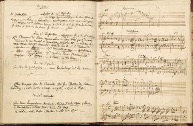

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.