Ailsa Dixon’s sonata for piano duet Airs of the Seasons, is the latest work to be published by Composers Edition, in a new edition by pianist Waka Hasegawa. This is part of an ongoing project to bring Ailsa Dixon’s music to a wider audience; the publication of scores of her music coincides with the release of The Spirit of Love, a landmark recording of her chamber music and songs on the Resonus Classical label. (Find out more here)

Airs of the Seasons is in four movements, each prefaced by a short poem, evoking in turn the magical stillness after a winter snowfall, the first stirrings of spring, a dragonfly darting over the water in summer, and finally amid the turning leaves of autumn, a retrospective mood which recalls the earlier seasons and ends with the hope of transcendence in ‘Man’s yearning to see beyond death’.

The sonata was unperformed in Ailsa’s lifetime, but in the months before she died in 2017 the score was sent to pianists Joseph Tong and Waka Hasegawa, who would give the work its posthumous premiere at St George’s Bristol in November 2018. A week before her death, Tong wrote with the news that they were already rehearsing: ‘It is a beautiful set of pieces and each of the movements evokes aspects of the seasons suggested in the poems in an original and imaginative way – the musical language itself and the way in which Ailsa creates four-handed piano textures are absorbing and distinctive.’ For a composer who received very little recognition in her lifetime, it was a poignant indication that her music would survive her.

In a review of the premiere, Frances Wilson (AKA The Cross-Eyed Pianist) wrote ‘The opening chords of the first movement are reminiscent of Debussy and Britten in their distinct timbres, and the entire work has a distinctly impressionistic flavour. Ailsa’s admiration of Fauré for his “harmonic suppleness” is also evident in her harmonic language, while the idioms of English folksong and hymns, and melodic motifs redolent of John Ireland and the English Romantics remind us that this is most definitely a work by a British composer with an original musical vision. The entire work is really delightful and inventive, rich in imagination, moods and expression.’

Airs of the Seasons has subsequently been performed for Wye Valley Music in 2019, for Wessex Concerts at St Mary’s church in Twyford near Winchester in 2022, and in a concert in 2024 celebrating Ailsa Dixon’s musical legacy at St Mary’s College, Durham University where she studied in the 1950s.

Order the score from Composer’s Edition here

This article, written by Ailsa’s daughter Josie, first appeared on the Ailsa Dixon website. Find out more about Ailsa Dixon’s music here

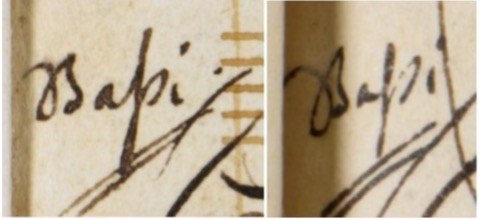

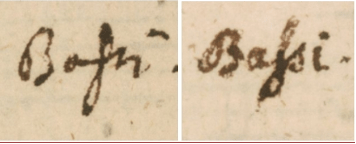

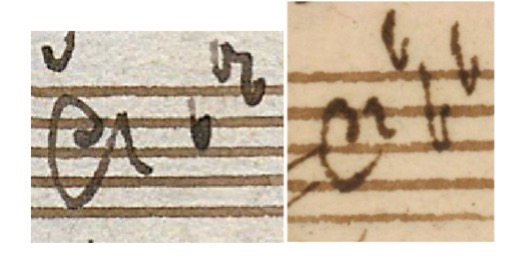

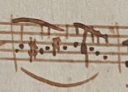

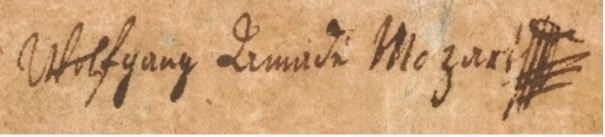

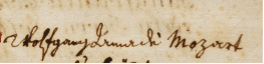

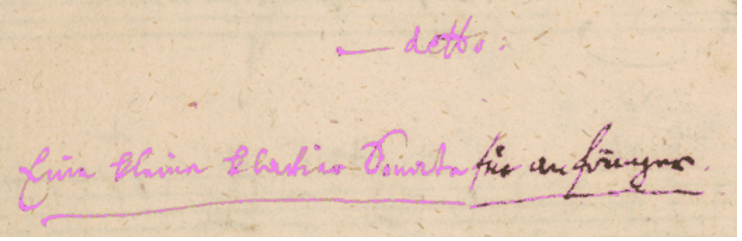

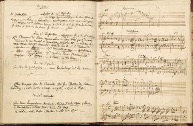

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.

The Thematic Catalogue, held in the British Library in London, is a small, ninety-page book in excellent condition. It is bound and features an elegant part-leather cover. Fifty-eight of its pages contain text and music. The catalogue is arranged with detailed descriptions of the instrumentation on one page and the incipits of the pieces—typically four bars written on two staves—on the opposite page.