Guest interview by Michael Johnson

A legend in contemporary piano music, Ursula Oppens has just turned 80 and shows no sign of trimming back her busy life of recording, performing, teaching and commissioning new works from American composers. She fights the aging process with tremendous vitality and mostly wins.

But as she told The New York Times recently, “The eyesight goes, the fingers, the retention”.

A few weeks later in my telephone interview with her, she was more optimistic. “My mind is still functioning the way I would like it to function. I am lucky to be very active at this time and I plan to continue.”

The Times rather bluntly described her as “a little fragile, tiny and stooped”. I tried to capture some of that in my portrait of her.

But she is also recognized as a powerful performer who tackles the thorniest of new pieces. As she said in our interview, she remembers hearing the difficult works of Julian Hemphill for the first time and thinking “This is for me!”.

Composers who have been commissioned by her or who have written works for her include such leading lights as Frederic Rzewski, William Bolcom, and Charles Wuorinen.

Perhaps her best known collaboration was with expatriate American Rzewski with whom she became “very, very, very close friends” and produced the now standard “People United will Never be Defeated”, a magnificent set of 39 variations. Some critics have classed it alongside Bach’s Goldberg Variations and Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations.

She worked together at a distance with Rzewski during the pandemic, ending with his musical tribute “Friendship”. As Oppens told me, we could not meet in person for two years but “he could write and I could play”.

In this clip she plays Rzewski’s “Friendship” on a Fazioli grand.

Her attraction to modernity took shape when she attended lectures and a concert at Radcliffe College with the young French composer Pierre Boulez. She was musically smitten and never looked back.

Edited excerpts from our recent conversation, recorded while she was at a music festival in North Carolina:

You have helped shape contemporary American music through your commissioning of new works. How did you become so interested in modernity?

My parents were refugees from Europe and they felt they had left a great culture behind. I found out much later in life that my mother had taken a course with Anton Webern. And my father joined the ISCM (International Society for Contemporary Music). So they had been interested in new music all along. I didn’t know that as I was growing up but it might have been an influence in ways I didn’t understand.

You are perhaps best known for your commissioning. Are there other people out there also looking for new works? Or are you alone?`

Oh no. There are people like that all over the place.

Where has the commissioning money come from? Family funds?

No, some has come from foundation grants. For example, I received a big grant from the Washington Performing Arts Society. But funding commissions can come from all kinds of sources.

When did you start commissioning?

I didn’t really commission until after college. The first composers I approached to write pieces for me were Tobias Picker and Peter Lieberson. I recorded both their pieces. One composer who had a great influence on me was composer John Harbison. I also played with this wife, the violinist Rosemary Harbison.

I believe the late Fredric Rzewski was among your friends. You knew him, didn’t you?

Oh yes, he was a very, very very close friend. I commissioned his “People United Will Never be Defeated”. The most recent piece I commissioned from him was “Friendship”. It was very much a pandemic piece. For two years we couldn’t see each other but he could write and I could play. He died at 83 in Italy during the pandemic.

You have a new CD coming out soon?

Yes, it’s the music of Charles Wourinen. Mostly solo piano but there’s also a ballet for two pianos that we still have to record. I knew Charles well and worked with him from 1966 to his death in 2020, maybe the longest relationship I’ve had.

What was your relationship with Julian Hemphill?

I lived with Julian for almost twelve years. He is a fine composer and a wonderful man. When I heard his difficult music I thought, “This is for me!”

In your CD “Winging It”, you featured the John Corigliano music that you had commissioned. Does that happen often? You commission something, the composer writes it and you record it. Is that how it works?

That’s what it’s all about. Yes, when you commission a piece it’s a little bit like having a child. You let the child go out into the world, make his own friends, and live his own life. What’s exciting is that after a while other people start playing it.

You seem to be focused on the American composers.

Basically yes, because American composers are people I can work with, people I can bump into. You want this personal contact and you become their friends, like Thomas Picker — I am very honored to be a friend of his, you know. Working with him has made my life very exciting.

Your fans worry about your health. Should they?

Not really. I work more slowly. I don’t run any more. But I’m perfectly healthy as far as I can tell. Of course as one gets older things get a little creakier. My mind is still functioning the way I would like it to function. I am lucky to be very active at this time and I plan to continue. I have had a wonderful share of happiness in my life.

What has aging done to your piano technique?

Luckily I don’t have any serious problems but I cannot say I play as well as I did when I was fifty. I am careful about expanding my repertory. I don’t take on impossible pieces, like Prokofiev’s eighth Sonata.

Are you slower, are you careful about your repertory?

Yes, recently I was teaching the Prokofiev. It was very sad that I had never played it. It’s too difficult a piece for me to learn at this point. I could practice but I probably would not be able to perform it.

But you could still teach it?

Oh yeah.

It is like a master class, I suppose? You play a few bars to show the way?

Not necessarily. You can point out the phrasing, and this and that. You’ve got to hear this note to make sense of the next one — and stuff like that.

Most of the musicians I talk to avoid contemporary music because it requires a lot of learning and they are not sure it’s worth the trouble. Is it really that difficult to master?

It can be difficult, yes, but often it is absolutely wonderful. There is no limit to how exciting it can be. It’s very, very thrilling. You bring to life something that has not existed before.

What about the limited reception by people who are not tuned into contemporary sound worlds? They say well, it’s not Mozart. Doesn’t that drive you up the wall?

No. Live music in a small hall with an audience of sixty people can be so wonderful. Sometimes I tell the audience to listen for certain passages. It makes it an exciting experience for them.

Do you have any fear of being slightly crowded out by the Asians who have suddenly discovered us?

No. If immigration were not part of America I would not exist. I am the daughter of immigrants. We are a mixture, and that is fantastic. I know some of the great young pianists are Chinese. There are people everywhere who can run better, who can jump better, and there are people who can play the piano better.

Do you have a swan song in mind? Are you even thinking of your legacy after the inevitable end?

I will keep making music as long as I can. I know that one day I won’t be able to, and that’s a normal part of life. But I don’t wish to be playing the harp for eternity.

(Ursula Oppens, portrait by Michael Johnson)

MICHAEL JOHNSON is a music critic and writer with a particular interest in piano. He has worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Moscow, Paris and London over his journalism career. He covered European technology for Business Week for five years, and served nine years as chief editor of International Management magazine and was chief editor of the French technology weekly 01 Informatique. He also spent four years as Moscow correspondent of The Associated Press. He is a regular contributor to International Piano magazine, and is the author of five books. Michael Johnson is based in Bordeaux, France. Besides English and French he is also fluent in Russian.

Michael Johnson, in collaboration with The Cross-Eyed Pianist (Frances Wilson), has published ‘Lifting the Lid’, a book of interviews with concert pianists. Find out more / order a copy

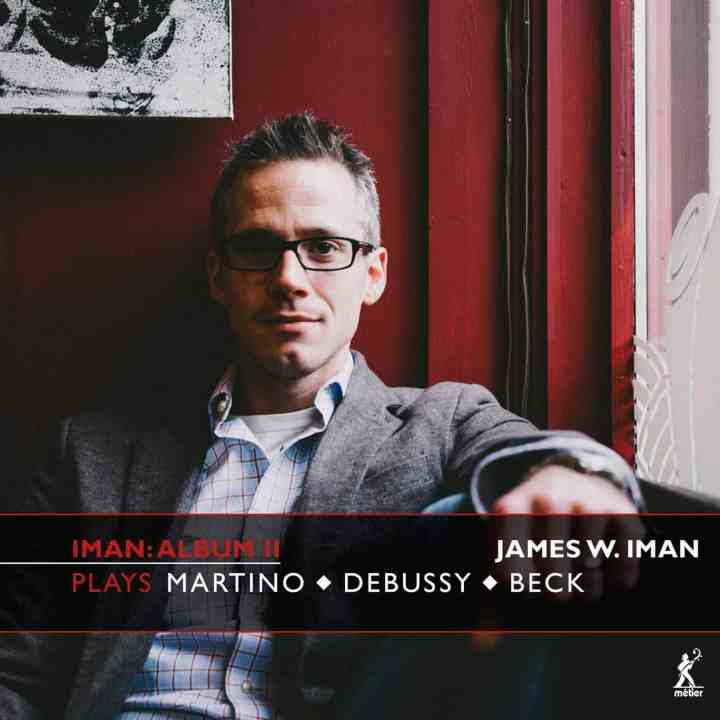

In his latest album, American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s everygreen Images alongside works by Jenny Beck and Donald Martino

In his latest album, American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s everygreen Images alongside works by Jenny Beck and Donald Martino