Several of my students have been learning and enjoying this well-known piece by the Penguin Café Orchestra, and so I thought it might be helpful to have some background.

The Penguin Café Orchestra (PCO) was a collective of musicians, founded by Simon Jeffes in the 1970s. It is hard to categorise their music, but it combines elements of exuberant folk music, and the minimalist music of composers such as Philip Glass and Michael Nyman. The music also contains references to South American and African music, and uses a variety of instruments including strings, pianos, harmoniums, slide guitars, cuatros, kalimbas, experimental sound loops, mathematical notations and more. A number of their works are very familiar as they have been used in film, tv and advertising.

Perpetuum Mobile is one of PCO’s most famous pieces, and comes from their fifth album, ‘Signs of Life’ (1987). The title is Latin for “perpetual motion” (or continuous motion) and in music it refers to two things:

- pieces or parts of pieces of music characterised by a continuous steady stream of notes, usually at a rapid speed

- whole pieces, or large parts of pieces, which are to be played repeatedly, often an indefinite number of times.

In both cases, there should be no interruption in the ‘motion’ of the music. Examples from classical music include the presto finale of Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor. Marked “sotto voce e legato” (literally “under the breath and smoothly”), the entire movement is a musical stream of consciousness of unremitting parallel octaves, with unvarying tempo and dynamics, and not a single rest or chord until the final bars. The difficulty for the pianist, aside from keeping the triplets absolutely equal and even throughout, is the sotto voce (a fairly common marking in Chopin’s music) which suggests a muted sound. Careful pedalling will, in part, create the desired effect but the sound should never become woolly or muddy: we want to hear every single note. This movement has a strange and mysterious cast: Arthur Rubenstein remarked that the fourth movement is like the “wind howling around the gravestones”, and a pianist colleague of mine described performing it as “horrible – like having your entrails picked over on stage”. Interestingly, Chopin himself said of the movement: “The left hand unisono with the right hand are gossiping after the [Funeral] March” (source: James Huneker in his introduction to the Mikuli edition of the Sonatas). Played well it is inscrutable and brief; played badly and it’s just a muddle.

Here is Ivo Pogorelich, with a good view of his hands at work

Schubert’s Impromptu in E flat is another perpetuum mobile, at least in the outer sections (the middle section of the piece is a rough gypsy waltz), which, like the example by Chopin, is built from almost continuous triplets in swirling, tumbling scalic figures which never quite break free from the secure tether of the bass line. The difficulty in this piece, as in the Chopin, is keeping the triplets even, though with some give-and-take/rubato and dynamic shading to add interest: unlike the Chopin, there is prettiness and charm in this piece, and the dance rhythm of the bass line should be highlighted too. My problem when I was learning this piece (or rather relearning – I first encountered it in my teens) was lifting the fingers too high, which produced a chunky, “notey” sound and interrupted the flow of the music. It also made my arm tense. I taught myself to keep the fingers curled into the keys and to start with a slightly higher hand position: the result was a pleasing “trickling” effect in the long scalic runs, and the piece was far less tiring to play.

Pedalling is another issue in this piece, and I had a long discussion with a colleague about this, who kindly heard my Diploma programme ahead of the exam. In the end, I compromised on 1/8 pedal: like the Chopin Sonata, you don’t want a muddy sound (and I’ve heard plenty of live and recorded performances of this work with some very sloppy pedalling!). The beauty of this music, in my opinion, is the clarity of the writing, and the elegant song lines which are subtly embedded in the triplet figures. Careless or over-pedalling won’t highlight these interior elements to the listener.

A further danger of this piece is getting so caught up in the perpetual motion of it that you forget to breathe! This may sound daft, but I can confirm that in my Diploma recital, I probably played the restatement of the opening section on one breath. And in rehearsal one afternoon, my page turner was so absorbed in the music, he forgot to turn over the pages for me!

Walter Gieseking:

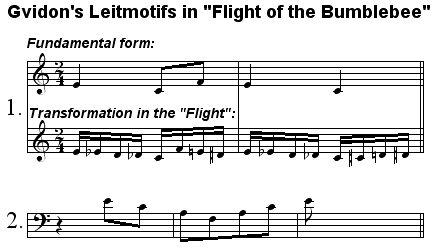

Perhaps the most famous example of a musical perpetuum mobile is Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumble Bee, an orchestral interlude from his opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan. This popular work, often performed as an virtuosic encore, consists of nearly uninterrupted runs of chromatic semiquavers, with leitmotifs (Givdon’s themes) from the opera. It is not so much the pitch or range of notes that present the challenge, but the sheer speed of it and the musician’s ability to move quickly around the notes.

Other famous perpetuum mobiles from classical music include Debussy’s ‘Mouvement’ for piano (from the first book of Images), and Francis Poulenc’s Trois Mouvements perpétuels.

PCO’s Perpetuum Mobile is built on a simple repetitive melody which is put through several harmonic and textural changes, building in grandeur as it goes. The repetitions of the melody make it a hypnotic piece, but the changes prevent it from being boring. Instead, the accumulation of elements and orchestration make this an energetic and exciting piece to listen to, and to play.

A friend of mine has adapted the music for easy piano (Grade 2-3 level), and although simplified, the music retains key features from the original, including the harmonic and textural changes. After the introduction, the main melody is introduced and repeated in the right hand before the left hand joins in with a progression of stern chords in open 5ths and octaves. Further along in the score, and both hands play the melody unison, reflecting the string articulation in the original. The two-bar melody, which is scored in 7/8 and 4/4, contains an octave leap which might be tricky for smaller hands. However, this also offers a great opportunity to practice ‘rotary motion’: I get students to practice the second, 4/4, part of the melody first, as the smaller stretches make rotary movement easier to grasp.

Before playing a single note on the piano, we practice rotary motion above the keyboard, or even away from the keyboard. Many teachers and tutor books describe rotary as “turning a doorknob” (an old-fashioned round doorknob, obviously) or turning cooker knobs. But my teacher and I decided the movement was more like the windscreen wipers of a car: it’s an “out-in” movement rather than “in-out”. To practice it at the piano, start in a 5-1 position, G-C (either Middle C position or an octave higher, if more comfortable), and place the hand in a “karate chop” position on the G with the fifth finger. Allow the hand to “flop” onto C with the thumb, and repeat. Encourage the student to watch the movement of the wrist: if the wrist isn’t moving, it ain’t rotating! Speed the movement up so that the student understands that it is the rolling (“rotary”) movement of the wrist that makes the sound, rather than the fingers. Keep the wrist and hand flexible and soft throughout: this will also help achieve a good tone.

Everyone I’ve taught this piece to wants to play it fast, but to try and play it up to tempo before you have practised rotary motion and grown comfortable with it will lead to tension in the hand and possibly pain. Keep the tempo sensible and perfect the rotary motion and good legato-playing before cranking it up. Meanwhile, enjoy experimenting with different dynamic levels for dramatic effect. The unison section should be light, nimble and nicely articulated to achieve the effect of the strings from the original.

Download the easy piano version from the SE22 Piano School blog

And the original, composed by Simon Jeffes:

A shorter version of this article was published on my sister blog, Frances Wilson’s Piano Studio