What is your first memory of the piano?

What is your first memory of the piano?

My first memory of the piano was when my parents bought an upright for my sister Alison who was beginning to learn the piano. I can recall it coming into the house quite clearly and I must have been about 4 years old. I was fascinated by it from the start and its grinning mouth of keys. At my first school, Milford, in Gerrards Cross, the headmistress, Miss France, used to play the piano for hymns and music classes. I can remember watching her hands and the way the keys went down. It is a vivid memory and it was Miss France who first encouraged me to play and gave me my first lessons. Initially, I did everything by ear and taught myself simple harmonisations of well known tunes like ‘The British Grenadiers’. I remember playing this during break to all the other children as we had our regulation bottle of milk.

Who were your most memorable/significant teachers?

Miss France, whom I mentioned above, was my first encounter with a piano teacher and she set me on the road. However, she felt I needed a more qualified teacher and she arranged for me to have an audition with Marjorie Withers who also lived in Gerrards Cross. She was an outstanding musician and teacher and I went to her when I was seven. It was she who really inspired me and had a gift for giving me pieces which really excited me. She also encouraged my playing popular tunes and improvising. I was heavily into Russ Conway, Winifred Atwell and Joe Henderson in those days and could do a passing imitation of them. At Downside School, where I boarded from 1964 to 1967, I also had remarkable teachers in Roger Bevan, the Director of Music, Lionel Calvert and Peter Matthews.

Who or what are the most important influences on your teaching?

I have mentioned the teachers I had as a boy and they all had influences on me, most notably Marjorie Withers. It was really she who laid the foundations of such technique as I may have, and who instilled in me the discipline of practice and ways in which to make it creative and effective. She was also a fine pianist herself and was well able to demonstrate, quite dazzlingly as it seemed to me, Chopin Studies, bits of Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Grieg, and numerous other composers. Her attitude, her sense of fun and celebration of the music deeply influenced me

Most memorable/significant teaching experiences?

Initially the pressures of having to earn a few pennies was quite an incentive to start giving lessons to local children and one or two adults. However, I do recall helping a friend at school, of no particular pianistic talent, to play a piece he was struggling with. I remember feeling a strong desire to help him conquer what seemed to be insurmountable difficulties! However, it was Gordon Green at the Royal Academy of Music who was the chief musical and pianistic inspiration and who continues to exert an extraordinary influence on me and many others who had the good fortune to study with him. His philosophy was to allow young people to develop at their own pace in their own time. Not for him the pressures of competitions, rushed learning and the resulting stress and misery which can follow. He used to say that his concern was not how you played today, but how you would play in ten years’ time. His wisdom, gentleness and encouragement enabled many of his students to go on to achieve considerable success. He was neither possessive nor ambitious except in the sense of wishing students to be balanced, fulfilled human beings who happened to play an instrument.

What are the most exciting/challenging aspects of teaching adults?

There are many issues but one is the tendency to choose too challenging a repertoire. Also nerves and confidence. Then there is physical condition, i.e. muscular flexibility. This can be very variable. In general my approach is always to build positively on whatever the situation presents. It is all too easy to be inadvertently discouraging and negative. Always be upbeat and positive. Quite often there have been bad, even traumatic experiences with past teachers and this can result in a general crisis of confidence which has never been fully addressed. Inevitably there is a tremendous legacy of vulnerability which must be handled with sensitivity and gentleness. The early lessons need to be a form of therapy with a bit of piano occasionally thrown in with no strings attached preferably! I often start with a course of simple exercises which involve the entire keyboard….a kind of embrace and bonding with the keys. It is also important do some simple pre-keyboard exercises, standing, bending stretching and relaxed breathing. It is also good to be aware of the prevalent danger of “wishful listening”. This is very common and accounts for attempting to play pieces before they have been sufficiently prepared and studied. The trouble is, a habit forms whereby the student doesn’t hear what’s actually being played, but hears an imaginary and vastly edited version which sounds, to their ears, acceptable…only it isn’t!

What do you expect from your students?

Expectations vary especially between college students and amateur adults. Inevitably more is expected from a young person embarking on a professional life of a musician. In the case of adult amateurs, those doing it for pleasure in such time as they have available, different expectations arise. I take each person as they are, as circumstances allow, and work within those parameters. However, I do always work at simple strategies which, if followed closely, can save endless hours of needless repetition…..which unfortunately so much so called “practice” can often be. An issue which often arises is the one of that dreaded word “tension”. I make a point of never using the word preferring to ask whether the students feels “comfortable” in a particular passage. Invariably the answer is uncomfortable, so I suggest that together we find a more comfortable way of doing it. This, in itself, reduces tightness and anxiety. To simply say ”that looks tense” exacerbates the problem and is, in my view, poor teaching psychology. I have found that many tension issues have not been addressed simply because the symptoms have been treated and not the cause. A tight wrist can be the result of weak fingers or an impractical fingering. It’s amazing what an unconventional fingering or a cunning redistribution can achieve…let alone the discreet omission of troublesome notes which can barely be heard. I rather hear fewer notes comfortably and confidently played than more, scrambled!

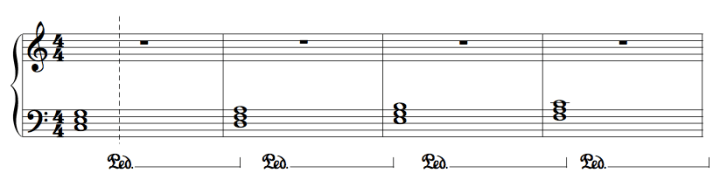

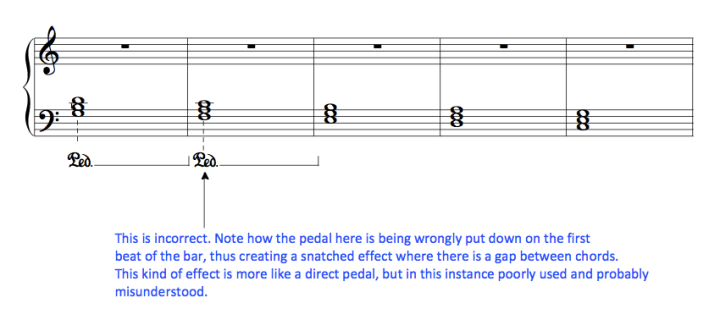

Another issue is the release of notes, usually caused by the notion that everything must be legato fingering. The horror of letting go and allowing the pedal to help in appropriate situations, is a real psychological and physical difficulty. The traditional tyranny has taught that not doing legato fingering is a mortal sin. There are ways of achieving legato other than holding on to notes in distorted and twisted ways which make a horrid sound and cause great discomfort. In saying this, I do not wish to mean that legato fingering is of no importance…. it is essential, but a realistic balance needs to be found and allowed for. Too often I encounter “off the peg” fingering – one size fits all. Only it doesn’t!

In general I find with adults, as with the younger generation, stretch and extension exercises have not been addressed. Fingers operate in isolation with one another. I encourage a dialogue between all the fingers so that they can get to know one another. Coordination exercises also can be of great benefit. So often fingers are complete strangers to one another, and rather hostile ones at that! Explore movement; find the slip roads on to the motorway. Ski, fly, grope the keys. When fingering, explore options, be daring. Give the fingers a choice. Within a very short time they will make their own decision….. and a good one provided they have the initial choice. Let the miserable, bald battery fingers out of their cages to roam free, grow feathers and lay big fat brown eggs. They’ll make a better sound. I call it Fowke’s Free Range Fingering. Your fingers will smile in gratitude and relief scuttling off into pastures new and sunlit glades.

Don’t get stuck on slow practice. Practice above tempo in short bursts, strong beat to strong beat to learn movements and gestures which can help the keyboard choreography. Practising slowly, though essential at all stages, does need an antidote. There can be a danger of practising to play slowly. Similarly with hands separate practice.

Practice pianissimo, or on the surface of the keys. Too much practice is too loud and too fast. Listen in your head. A good maxim, though not invariable, is to practice loud passages pianissimo, and piano passages forte. Similarly, practice slow movements quickly and quick movements slowly. Play in different registers, crossed hands, even in different keys. Muck about. Practising can be like a kitten teasing a ball of wool. I always remember Shura Cherkassky saying to me that if I heard him practice, I wouldn’t think he could play the piano. This made an indelible impression on me at the time and beautifully describes real practice…. a craft that has to be carefully honed. Learn to dismantle a piece down to the tiniest component.

We press keys down, but do we consider the release? Same with the pedal. Practice the sustaining pedal with the left foot. Concentrates the mind and ear wonderfully!

What are your views on exams, festivals and competitions?

Very mixed. They all have their place but in my view far too much emphasis is put on the competitive element and too little on the musical and artistic elements. Performing in public has become an international sport and the list of sporting casualties and injuries grows proportionately. We need to review the number and regularity of some of these major competitions…..and the way the media promotes them. As to exams, again they have their place, but it is noteworthy that countries where the graded system does not exist produces playing of a singularly and consistently high order from an early age.

What do you consider to be the most important concepts to impart to beginning students, and to advanced students?

This is difficult to condense into a few simple sentences. If I have one thing to say it is that so many pianists of whatever age, ability and experience have little concept of the keyboard. They have never been encouraged to explore it, to improvise, to be allowed to make nasty noises eventually leading to rather more beautiful sounds. An intrinsic fear lies at the core of so much playing; fear of wrong notes, fear of going wrong. All this is caused by a basic lack of harmonic awareness, a hazy knowledge of scales and arpeggios, and an inability to busk and improvise. Teachers pass on their own fear as they themselves were never encouraged to improvise to play with the keyboard rather than on it. The tyrannical pull of middle C reigns supreme I fear!

What do you consider to be the best and worst aspects the job?

I’m not sure I can answer this. Teaching is not exactly a job for me, more a mission. I simply want to explode myths, to enable and to explore, to reveal the keyboard as more than an extension of middle C

What is your favourite music to teach? To play?

Well, of course it is always a pleasure to work on familiar core repertoire. However, I do enjoy the challenge of unfamiliar scores which nobody has issues with, received opinions and which no one has ever heard before!

Who are your favourite pianists/pianist-teachers and why?

This is dangerous territory and one I have consistently tried to avoid!

Is there a link between teaching and performing?

It has been said that performers don’t make good teachers. Well, this is true in some cases but certainly not all. Equally I know of some good teachers who don’t, and never have to any significant degree, performed in public. However, having said that, the experience of performing, the physical and psychological act, does possibly lend one’s teaching an element of realism and practicality. Knowledge and respect for the score is well and good, but how to deliver it? What I describe as health and safety editions with their plethora of notes and commentaries, foot and note disease, can be daunting. Nothing is left to chance and this can inhibit performance rather than inform it. Performing in public can give a teacher the insight into that which is to be aspired to, that which is feasible, and the experience to make the choice.

Philip Fowke, known for his many BBC Promenade Concert appearances, numerous recordings and broad range of repertoire performed worldwide, is currently Senior Fellow of Keyboard at Trinity College of Music. He is also known for his teaching, coaching and tutoring in which he enjoys exploring students’ potential, encouraging them to develop their own individuality. He is a regular tutor at the International Shrewsbury Summer School as well as at Chethams Summer School.Conductors with whom he has worked include Vladimir Ashkenazy, Rudolf Barshai, Tadaaki Otaka, Sir Simon Rattle, Gennadi Rozhdestvensky, Yuri Temirkanov and the late Klaus Tennstedt. He will shortly be recording piano works by Antony Hopkins CBE in celebration of the composer’s 90th birthday. In addition to Philip Fowke’s many invitations to tutor at festivals, summer schools, and numerous lecture recitals, he will be appearing with The Prince Consort, a group founded by his former student Alisdair Hogarth. Their recent recording for Linn Records featuring works by Brahms and Stephen Hough, has received outstanding acclaim, and was nominated CD of the month by Gramophone Magazine. Future appearances include the Wigmore Hall, Purcell Room, Cheltenham Festival and the Concertgebouw Amsterdam.

www.philipfowke.com

What is your first memory of the piano?

What is your first memory of the piano?