An interview with celebrated baritone Benjamin Appl ahead of his appearance at this year’s Leeds Lieder Festival

Who or what inspired you to pursue a career in music and who or what have been the most important influences on your musical life and career?

I started to sing when I was pretty young. Although no one in my family had trained as a professional musician, we sang a lot together while my mother accompanied us on the guitar. Aged ten I followed my two brothers and joined one of the most renowned boys choirs, called the Regensburger Domspatzen (which means the ‘cathedral sparrows of Regensburg’). Originally I wasn’t so fond of boys singing together – I disliked the sound and thought it sounded shrill – but after being part of this choir community and experiencing that amazing feeling of making music together on such a high level, I then really loved it. I think this was the moment when this addiction was first planted inside me, the feeling that life without music would not be the same.

Then, as a professional musician, of course it was my teacher and mentor Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. To have had the privilege of working with him is one of the highlights of my career to date. He was a real mentor in many ways and taught me so much, not just vocal technique or interpretation but much more beyond this: he taught me the essence of being a musician, and the responsibilities with which that comes.

I was deeply impressed by his level of preparation, and the seriousness with which he achieved such a deep level of understanding of the music. Every time I went to his home he had prepared himself for our session, looking through the scores again, reading about the poetry and the background of the songs – doing all this even though he had already spent a lifetime on it. But this is also one of the most wonderful aspects of this profession: you never can be too well prepared.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

I think what’s important is to find a personal connection with the music and how to present it and how to communicate it to people. If you’re yourself and you try to find a good emotional connection and how to communicate it, then it can be fairly easy. Generally, though it’s quite a difficult job in that as a singer, you carry your instrument with you 24 hours a day! We can’t, like a pianist for example, leave the instrument at home for two hours in the evening and go to the pub. That’s also something else we have to live with regarding our instrument – we have to accept when it’s not working and to be kind to it. That does mean that it can be difficult not to become too self-centered and think only about ourselves. That is something very challenging and we have to find ways to cope with it.

Of which performances/recordings are you most proud?

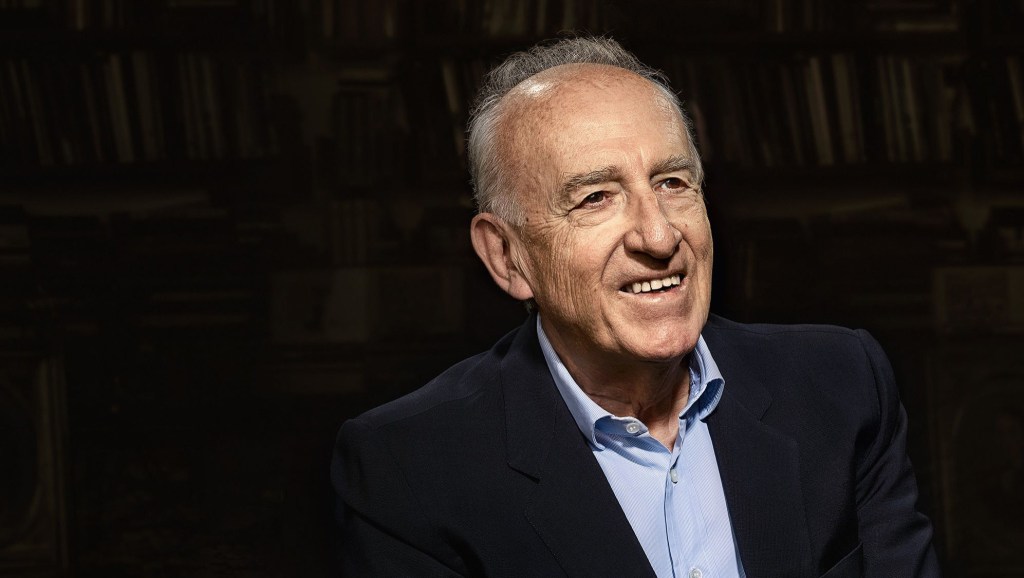

Actually, it will be one of my forthcoming album releases, a project I have been involved with for quite some years now. Together with one of the greatest contemporary, living composers György Kurtág, I am recording some of his compositions as well as songs by Franz Schubert, where he, aged 97, plays the piano. The working process with him is incredibly detailed and challenging, but the rewards are at a level you normally never experience anywhere else.

Which particular composer do you think that you perform best?

I probably would say Franz Schubert. With him and his music I feel most at home, not only because I spent the most time with his music and learned around 400 of his songs by heart. There is something in his music which gets right into my heart – how he creates an environment, a beautifully carpeted pathway, for the poetry to speak directly to the listeners. There is no extraneous material or conceit; the musical textures ar. He is a composer who somehow stands with both feet on the ground. His music feels somehow deeply rooted inside me and I resonate with his sentiments in his music – and therefore I think I can transfer this connection the best also to the audience.

What do you do off stage that provides inspiration on stage?

Finding inspiration is a key element of our profession. We give so much on stage and every evening try to give what we can that we actually have make sure that we fulfil own our inner inspirations – to go to museums, to casually observe life passing by in the underground in how people move around and suddenly think “This is a character in this song.” I enjoy wonderful times with other inspiring people, listening to their stories, being curious, having every pore of your body open so as to find inspiration again a new way of interpreting songs. Also always questions about why we do it this way, why this tempo, why do we take time here, why is this word important for us etc so that we actually create and never just deliver.

How do you make your repertoire choices from season to season?

It really depends on the different kinds of inspiration I get from outside or from within myself. Often reflecting on processes lcan ead to a different direction which you didn’t plan on and then of course the choices also depend on the interesting offers which are given to you.

Do you have a favourite concert venue to perform in and why?

Of course there are certain parameters which are important in a venue. Mostly it’s about the acoustic, so that you as a singer have the feeling that the space is giving you something back, and enhancing the reverberation of your own voice. But just as important is an ambience which makes you feel welcomed and comfortable when you enter. A good piano for my accompanist doesn’t hurt either!

But what would even an ideal venue be without an open and attentive audience? Especially for song recitals which are in many ways presented as a dialogue: even though one party is usually silent, it is an exchange of emotions and very much a shared experience. So the ideal really is to have a wonderful audience who is willing to be taken by the hand to go on a journey together.

What is your most memorable concert experience?

There are a few. Of course someone now would expect me to name performances in the biggest, most prestigious halls around the globe. But for me very often these ‘stellar moments’ happen under different circumstances: music is a comfort for me in moments of solitude or sorrow, and exaggerates my happiness in joyful moments. Performances which stay with me forever are very often linked with big moments which happened in my private life at the same time, like the loss of my grandparents, when I had to go out on stage and sing songs about facing death or mourning the loss of beloved ones; but also when I fell so deeply and freshly in love.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

Often I hear people say that art song is dead or that we cannot connect anymore to all those old texts and music. And I think exactly the opposite. All these songs are about emotions and feelings we carry very deeply in us, essentials like falling in love, being disappointed, loss of a beloved person or solitude – strong feelings we all can connect with and have experienced. I think within this art form there lie many opportunities and I am constantly searching for ways of combining it with other art forms or putting it in a current context. As a performer I experience very strongly that these songs make me understand myself and others better: My definition of success is when the same happens to my audience, that people connect with each other, go together on a journey and start a process of reflecting.

What advice would you give to young/aspiring musicians?

Find the right balance in life of the amount of performances, travel, working hours and try to have an interest or hobby outside music, which gives you the opportunity to put music aside for a moment and find pleasure and happiness somewhere else as well. It will only enrich your musicianship in the end.

What do you feel needs to be done to grow classical music’s audiences?

The field of Art Song is a bubble within the classical music world, which is a bubble in itself. So, I am very much aware that we will never have huge audiences or huge crowds and millions of people listening to us, but that is also fine to accept. I think that generally, elderly people who have more time in their lives, who don’t have to worry about small kids, or making a lot of money in their jobs, or having to learn a lot in schools etc have the luxury of time. And when you do some recitals, you have to focus fully on the music and the text. It’s not something which you can listen to on playlists or during to a fancy dinner. It really requires one’s full attention. And that’s challenging in the 21st century when everything’s very hectic and people have a short attention span. So that’s a reason why I think particularly people listening to song cycles are very often are in the second half of their lives.

I’m trying with my own programmes to go into schools and bring this Art Song to schoolchilren to try and make them curious about this music. It’s very important to plant the love I feel for this music into the hearts and ears of these young people so that at least they have the chance to encounter it at a young age and to see that other people are passionate about it.

What’s the one thing in the music industry we’re not talking about which you think we should be?

I think it’s wonderful that there are so many young people interested in studying singing or classical music. In colleges there are so many applications, like never before, so that’s something very positive. I find the lack of interest in politics and about people in the arts quite worrying. There are so many studies around the world which show the impact of music on human brains, on children such as how it makes them better human beings with better social skills, but also they learn other subjects faster, like languages etc. There is only good in it and I find it strange that no politicians really see the huge impact of music and how important it is. We have to plant music and art into the brains and hearts of young people. And even if they don’t like it in the beginning, I think it’s important that they have the chance to encounter it so that when they get older and listen to classical music they feel familiar with it. If they don’t get the chance from the very beginning it’s very hard later on to really understand this world which is so important in shaping for everyone. That’s something I feel very passionate about.

What’s next? Where would you like to be in 10 years?

There are so many ideas and interesting places to perform. I would love to perform song recitals for example like Schubert’s ‘Winter Journey’ in the Arctic. Pushing boundaries with other art forms, and strong collaborations. I have so many ideas in my mind that it’s sometimes overwhelming! I definitely have to write them all down, firstly not to forget them, but also to focus my mind on one idea. I have so many ideas all the time and would love to go in different directions, work with different people and never loose the joy and filfillment in performing. Just probing the horizon, being curious, not thinking in boxes but outside my box, and appreciating other people and their work and their love.

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Despite the stress and demand of my life as a professional singer I always try to remember that it is a huge privilege to live this life. Sometimes I ask myself the question if there is anybody in this world with whom I would like to swap lives and I can always truly say that I am most happy and there is no one with whom I want to exchange life – as long as I can say that, I am very happy with this accomplishment.

What is your most treasured possession?

Due to my profession, I feel like I spend a huge amount of my time researching and booking transport and then travelling from one concert hall to the next. In work circumstances, I often have to prioritise speed as time can be tight and pressure is high. As an antidote to that, a few years ago I bought an old Volkswagen Beetle: a beautiful red convertible from 1974 which I love to drive around the beautiful Bavarian landscapes with their with mountains, lakes and castles. Driving my little car relieves all the stress I typically experience whilst travelling and it calms me in a wonderful way. Also when the roof is open, I get the feeling that I can appreciate the surrounding nature so much more.

What is your present state of mind?

I often ask myself how does doing the kind of work I am doing in the arts change me as a person and as a creator. In this process of reflection, we have to be open, we have to find inspiration and that’s something, of course, that has a huge influence on ourselves as musicians. As singers, if we change our daily routine, we have to be careful with our voice, we can’t have the wildest life before performances, and so on. And the curiosity we have as an artist influences us very much.

The way of reflecting about ourselves, that we try to become better and better, is also something which changes us. I think of course, the art and the voice are so dominant in our lives as singers and really leading our lives, that we have to follow the music and the voice as a person within our life.

Benjamin Appl appears at this year’s Leeds Lieder Festival which runs from 13 to 21 April 2024. Full details/tickets here