Is this the most relaxing piece of classical music? asks Radio Three of Arvo Pärt’s contemplative and spiritual ‘Spiegel im Spiegel’. “If you ever need just eight or nine minutes to calm down, relax, switch off from the world, this is the piece you want to do it to…..” says pianist James Rhodes in his introduction to the piece in an episode of Saturday Classics on BBC Radio Three.

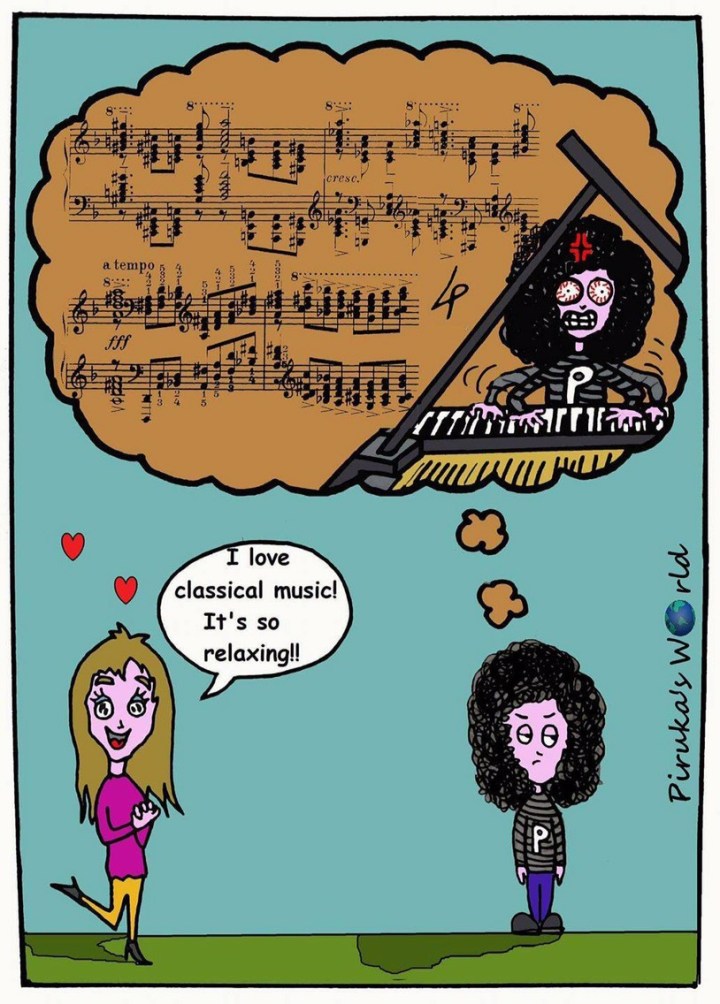

“Relaxing” is not a description I’d immediately associate with this piece – it’s far too trite for such a sophisticated work (its sophistication lies in its absolute simplicity and the austere rigour applied to its construction) and the word undermines the power of this music. (More about ‘Spiegel im Spiegel’ here).

Over on ClassicFM, great swathes of its programming and website are devoted to “relaxing classics” and “smooth classics”: “the most relaxing music ever composed” states the station of a list of works including Debussy’s Claire de Lune, Gymnopedie No. 1 by Satie, the slow movement of Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto and Einaudi’s ‘Berlin’. Alex James, formerly of the pop band Blur and one of the station’s presenters, declares “I find all classical music relaxing to be honest“. Does he include the ‘Rite of Spring’ in this, Handel’s ‘Hallelujah’ chorus, ‘Night on a Bare Mountain’, or Mahler’s ‘Resurrection’ symphony? Or maybe he’d prefer to chill out to Penderecki’s ‘Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima’, which opens with shrieking strings, redolent of fingernails being dragged across a blackboard…… Mr James’s comment suggests he is the victim of “restricted listening”, and that he has only experienced music which is serene, slow, soothing, calm, contemplative….. Mind you, since much of what is played on ClassicFM includes a lot of “meandering ersatz-symphonic film music and post-minimalist mush”, it’s perhaps not surprising that Mr James finds this kind of music “relaxing”. Personally I’d rather set my hair on fire and put it out with a hammer than listen to the dreadful ‘Ashokan Farewell’, ‘Gabriel’s Oboe’ or ALW’s ‘Pie Jesu’……

Anything by Einaudi transports me to another world, and I can day dream to my heart’s content

– Margherita Taylor, Classic FM presenter

There are any number of articles and scientific studies out there vaunting the therapeutic benefits of listening to music. Calm, soothing and (usually) slow music has been proven to alleviate stress, lower heart rate and blood pressure, and ease depression. Music can provide a great comfort and a place of retreat or escapism, and from the Orpheus legend onwards, music has been praised for its ability to soothe: Bach may have written his Goldberg Variations to ease insomnia, and Haydn wanted his music to ‘give rest to the careworn’. British-German contemporary composer Max Richter has written an entire work (lasting over 8 hours) based around the neuroscience of sleep. Today, a whole industry seems to have been built on the premise that classical music is “relaxing” and it continues to prove a great marketing tool for record labels and some radio stations (you know which one I mean…..)

When any music of complex structure and energy is contextualised as a commodity to fit an objectified market-driven demand and that market begins to classify all music in the broadest affective terms to meet that demand, and people actually start to believe it through adopting the trend, they swap a multicoloured, multifaceted world for a one-dimensional, dumbed-down, monochrome fake!

– Marc Yeats, composer

But to describe classical music simply as “relaxing” does a great disservice to so many works in the repertoire, reducing them to musical wallpaper or unobtrusive background noise instead of valuing them for what they really are. It mocks the achievements of Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov et al. It suggests that classical music is harmless and benign, and discourages engaged or attentive listening. If we constantly speak of classical music in this way we devalue it, undermine its greatness and its huge variety, and peddle the idea that it’s all “easy listening” – and if we do that, how do we introduce classical music newbies to composers such as Mahler, Schoenberg, Sibelius, Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Messiaen, Ligeti, Crumb, Ades, Birtwistle……? And assigning classical music the function of “relaxing” background music, to be played while you complete your tax return or cook dinner, is equivalent to describing it as “boring” – which anyone who has given the vast, wonderful repertoire a chance will know just isn’t true. But if it’s playing in the background, your ears won’t be fully open to it.

I don’t believe listening to classical music should be regarded as a passive activity. It was, and is, written by sentient people, people with emotions to share or a message to convey. It is born out of love, death, triumph, tragedy, loss, war, power, joy – feelings we can all connect to even if we cannot know the exact emotions of the composer at the time of writing. It was, and is, intended to fascinate the ear, stimulate the mind and elevate the soul and senses. It should shock, awe, terrify, annihilate, grab you by the throat, leave you breathless and have you listening on the edge of your seat. Active, engaged listening puts us in touch with the visceral qualities of music and human emotion. If classical music makes you relax, it has failed. It should be challenging and thought-provoking, because it has to something to say.

Music serves many purposes and we each listen and respond subjectively and intensely personally to what we hear. It can be transporting, taking us to other realms of our imaginations. It can evoke powerful emotions, recall past events or people, provoke a Proustian rush of memories. It can excite, amuse, tease. It can be deeply unsettling or ethereally serene. It can reduce us to tears or make us laugh.

You’ve got to hear this! It’s not meant to be relaxing.

Of course there are many works which are indeed “easy on the ear” – attractive, accessible, lyrical, melodic music which is immediately appealing (a quick glance at the Classic FM ‘50 Relaxing Classics‘ album reveals music which is generally slow and highly melodic). But is it all “relaxing”?

We need our advocates — composers, performers, educators, critics, orchestras and other institutions, and Lord yes, our radio stations — trumpeting what’s so vital in this music, inspiring the public to explore the repertoire and discover its power, so transformational that legions of us have dedicated our lives to creating it, sharing it, and supporting it.

– Patrick Castillo, composer

When I posted Alex James’s moronic comment on Facebook, I received a flurry of replies and some great examples of music which is anything but relaxing. I’ve even compiled a playlist of music which suggests all manner of emotions and scenarios, guaranteed to raise the heart rate and even the blood pressure on occasion!