British-based composer Naresh Sohal was born on 18 September 1939 in Punjab in pre-Partition India, and was the first person of Indian origin to make his mark as a composer of western classical music. His family had no musical pedigree, nor any connection with western classical music; his musical tastes were formed by listening to music on All India Radio and Radio Ceylon. A broadcast of Beethoven’s Eroica symphony on All India Radio gave him his first taste of the full power of the orchestra and its ability to create complex soundworlds, and he was so overwhelmed by this experience that he begged his father to allow him to travel to Europe so that he could become a composer of western classical music.

He had no formal musical training, beyond a handful of uninspiring night school classes in composition and a brief stint as a student of teacher/composer Jeremy Dale Roberts, but he got a job as a copyist for music publisher Boosey & Hawkes, which gave him the opportunity to study scores in depth, absorb compositional techniques and gain important insights into the way contemporary music was developing in the 1960s.

He completed his first large-scale work, Asht Prahar for orchestra, in 1965, and from there enjoyed a busy and productive creative life, composing well over 60 works, including major pieces for orchestra, chorus and soloists; chamber works; a ballet score; two musical theatre pieces; and scores for several television programmes. Of his eight commissions from the BBC, two were for major Proms pieces, and he had more than forty broadcasts of his work. He was the first composer to receive a bursary from the Arts Council of Great Britain, he served on the BBC music committee for some years, and in 1987 was awarded a Padma Shree (Order of the Lotus) by the Government of India for his services to music.

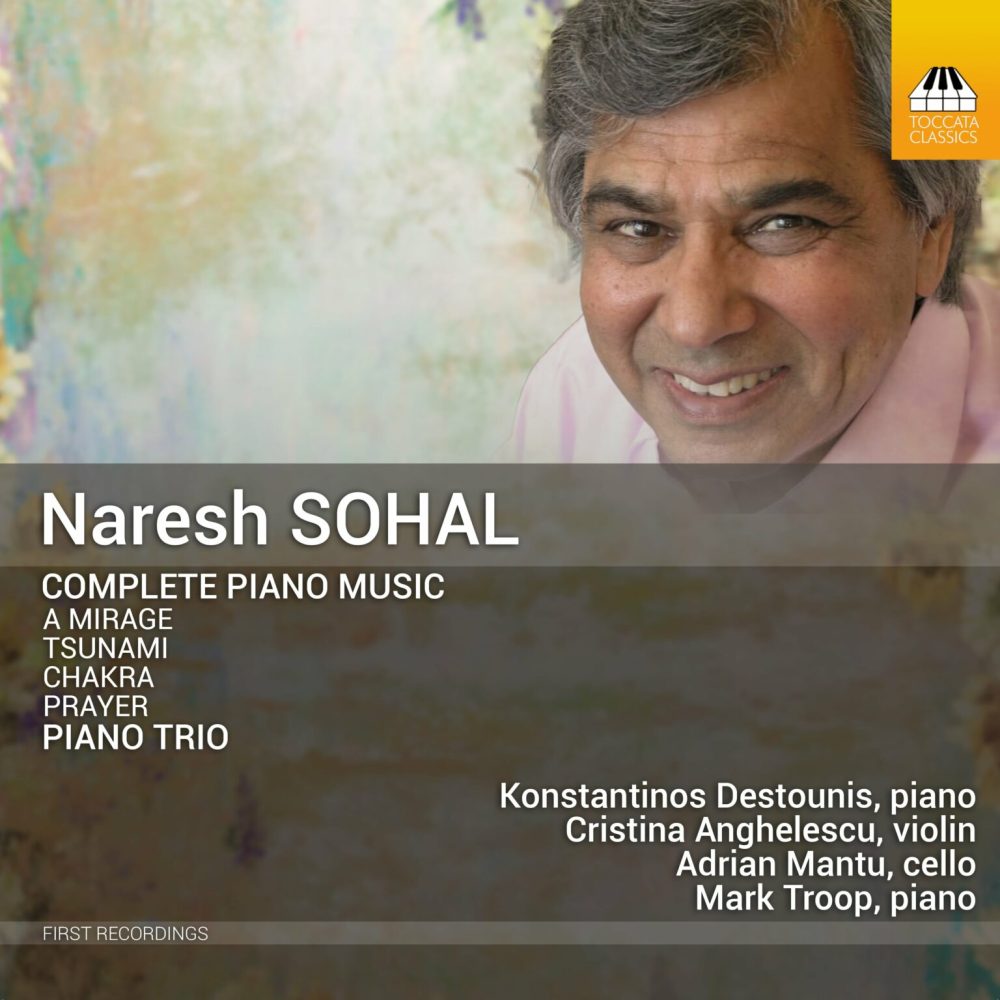

Toccata Classics released a recording of Sohal’s complete piano music (and his piano trio) in 2023, commissioned by Sohal’s widow Janet Swinney and performed by pianist Konstantinos Destounis. Here are a handful of works, written between 1974 and 2018, which illuminate a defining characteristic of Sohal’s music – a mysticism which explores issues of perception and the basis of human existence, and seeks a connection with the divine. This is manifested not only through the titles of the pieces – A Mirage, Chakra, Prayer, Tsunami, for example – but the music itself, whose unfolding soundscapes, suggest sacred rituals, contemplation and transcendence.

‘I am fascinated by the ultimate human questions of who I am and where I come from, and therefore most of my music is dominated by philosophical answers that are nearest to Vedantic thought’ – Naresh Sohal (interview with Suddhaseel Sen)

Throughout, there is a sense of a composer completely at one with the piano’s sonic capabilities, from plangent, sombre notes deep in the bass to the bell-like clarity or delicacy of the high treble register. The piano is a percussive instrument and Sohal utilises this with arresting effect in, for example, the opening piece, A Mirage, a work of some 13 minutes in which notes tumble across the keyboard, each with its own dynamic and colour. It’s a work of complex textures and emotional profundity.

Unlike the other works on the disc which are single-movement pieces, Prayer is in two movements, Adagio and Allegretto. The first movement has tender, perfumed chords, somewhat reminiscent of Debussy, and a plaintive melody. With its descents and ascents, each time reaching a higher note and growing more intricate, Sohal evokes the overwhelming power of prayer and spiritual transcendence. The second movement is toccata-like, its scurrying contrapuntal passages, interrupted by off-beat chords, representing the act of ‘pranam’ (prostration) or bowing forward in prayer.

Sohal’s final piece for solo piano, Tsunami, uses eastern scales with low bass notes to suggest the depth and movement of an ocean tsunami. The work’s steady tempo suggests the ominous, unstoppable power of water.

Despite the fiercely virtuosic complexity of Sohal’s music, pianist Konstantinos Destounis rises to its physical and emotional challenges to bring persuasive colour and clarity, control and sensitivity to the pieces on this recording.

An ideal introduction to Naresh Sohal’s music, his Complete Piano Music is released on the Toccata Classics label.

Further releases are planned for later this year – Janet Swinney writes: “One of these is a new recording by The Piatti String Quartet, currently quartet in residence at King’s Place, London, of four of Naresh’s five string quartets . Two of these pieces have never been performed before, and one of them is dedicated to me. The recording will be released by Toccata Classics. The project received a small financial subsidy from the Ralph Vaughan Williams Foundation.

There will also be two releases of heritage recordings of some of Naresh’s orchestral works remastered by, appropriately enough, Heritage Records.

CD1 comprises ‘The Wanderer’, Naresh’s first work for the Proms, based on the Anglo Saxon poem of that name. The work is for orchestra, chorus and bass-baritone soloist. The premiere was given at the 1982 Proms by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, with the BBC Singers and David Wilson-Johnson as the soloist, all under the baton of Andrew Davis.. The second work is ‘Asht Prahar’, Naresh’s first publicly performed orchestral work, premiered in 1970 at the Royal Festival Hall by the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Norman del Mar. The work concerns the division of day and night into eight equal intervals, according to the Indian system of time-keeping.

CD2 features ‘Lila’, a musical account of the process of meditation and the attainment of enlightenment. This was commissioned by the BBC Symphony Orchestra who gave the first performance at the Royal Festival Hall in 1996 conducted by Martyn Brabbins. Sarah Leonard, soprano, was the enlightened soul who appears at the very end of the piece.

This work is accompanied by Naresh’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, another BBC commission this time premiered in Glasgow in 1993 by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under Martyn Brabbins. Xue Wei was the soloist.

Find out more about Naresh Sohal’s life and music here

This article first appeared on sister site ArtMuseLondon.com

This site takes many hours each month to maintian and update. If you find value and pleasure in what I do, why not