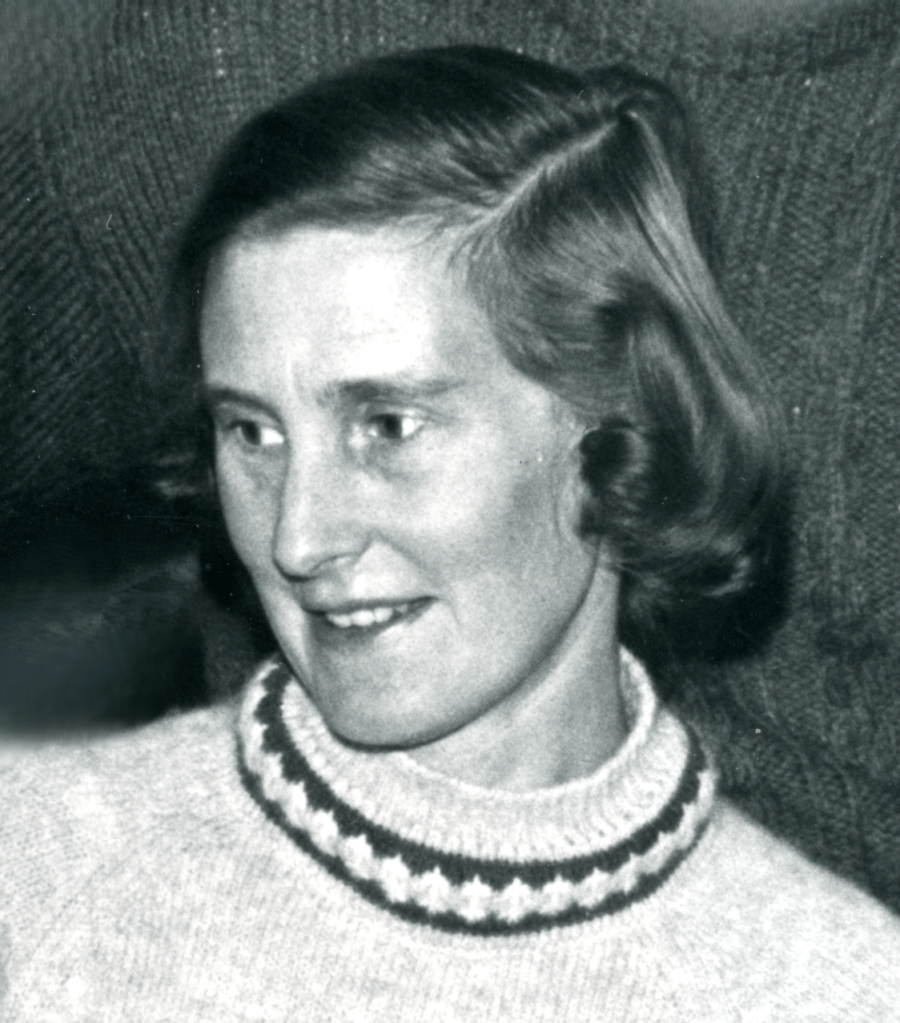

An important new recording, ‘The Spirit of Love’, featuring chamber music and songs by British composer Alisa Dixon (1932-2017), will be released on the Resonus Classics label on 22nd August.

This landmark recording highlights Dixon’s chamber works, many of which have remained largely unknown, until now. With the combined talents of the Villiers Quartet, soprano Lucy Cox and ondes Martenot player Charlie Draper, this recording represents a vital step in rediscovering the depth and breadth of Dixon’s music.

Born in 1932, Ailsa Dixon began composing before reading music at Durham University, and later studied with Paul Patterson, Professor of Composition at the Royal Academy of Music. Her works include a two-act opera, several pieces for string quartet, songs, chamber music and instrumental works including a sonata for piano duet.

In July 2017, five weeks before she died, her anthem for choir, These Things Shall Be, was premiered by the London Oriana Choir at the Cutty Sark in London. This marked the beginning of a revival of interest in her music and has led to a host of new performances of choral, vocal and instrumental works in concerts across Britain

Hailed as a ‘stunning find’, with its ‘lush harmonies’ and ‘strange yet still beautiful dissonances’ (Nottingham Chamber Music Festival, 2024), The Spirit of Love gives the title to this recording – a selection from her most fertile period of composition in the 1980s and 1990s. One of the many works found in Ailsa Dixon’s manuscript archive after she died, these songs for soprano and string quartet were premiered posthumously at St George’s Bristol, where a spellbound reviewer for the British Music Society registered ‘a feeling that something special had just occurred’.

A collection of three songs for soprano and string quartet, composed between 1987-88, and originally commissioned through Dixon’s lifelong musical friendship with Irene Bracher, The Spirit of Love sets texts by Dixon herself, along with works by A.E. Housman and F.W. Bourdillon. The work was given its posthumous premiere in 2020 at St George’s Bristol by the performers on this recording.

Another distinctive piece is Shining Cold for soprano, ondes Martenot, viola and cello. This work is characterized by its haunting vocalise and uniquely explores the sonorities created by the soprano voice, strings, and the ondes Martenot, an electronic instrument famously associated with Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie. This work highlights Dixon’s innovative use of instrumentation and vocal expression.

Other significant works on this recording include:

The ‘lost’ Scherzo for string quartet. Written in the 1950s while Dixon was at Durham University, this piece disappeared for over half a century before the manuscript came to light after her death. The recording presents its first performance, 70 years after it was written. Its changes of time signature may show an early interest in Bartok whom Dixon cited in later life as an inspiration for his ‘elasticity of musical motifs’.

Sohrab and Rustum for string quartet. This ambitious, through-composed work from 1987-88 was inspired by Matthew Arnold’s poem of the same name, depicting the tragic encounter between a father and son in battle. The music is a vivid response to the poem’s human drama and atmospheric setting.

Variations on Love Divine for string quartet. Written in 1991-92, this is Dixon’s final string quartet work and an exploration of religious chamber music, perhaps inspired by Haydn’s Seven Last Words. Woven around John Stainer’s Anglican hymn tune, it explores themes from St John’s Gospel, the Incarnation, Nativity, Passion and Ascension, culminating in a vision of heavenly joy. The Villiers Quartet recently gave the work its first complete concert performance.

This is more than just a new album; the release of The Spirit of Love represents a pivotal moment for the rediscovery and appreciation of Alisa Dixon’s diverse and compelling chamber music – music which combines lyrical lines, adventurous harmonies, and a spiritual undercurrent, brought to life with vibrant intensity and finesse by the Villiers Quartet, Lucy Cox and Charles Draper. This recording offers listeners an insightful journey into the rich, previously under-exposed world of a significant British composer.

The project has received support from the Vaughan Williams Foundation, and the release of this recording coincides with the publication of Ailsa Dixon’s scores by Composers Edition, making much of her previously unpublished material available for the first time, thereby enhancing scholarly and public access to her complete works.

Scores of the pieces featured on the recording are available from Composers Edition. The album is released on the Resonus Classics label, on CD and streaming, on 22nd August.