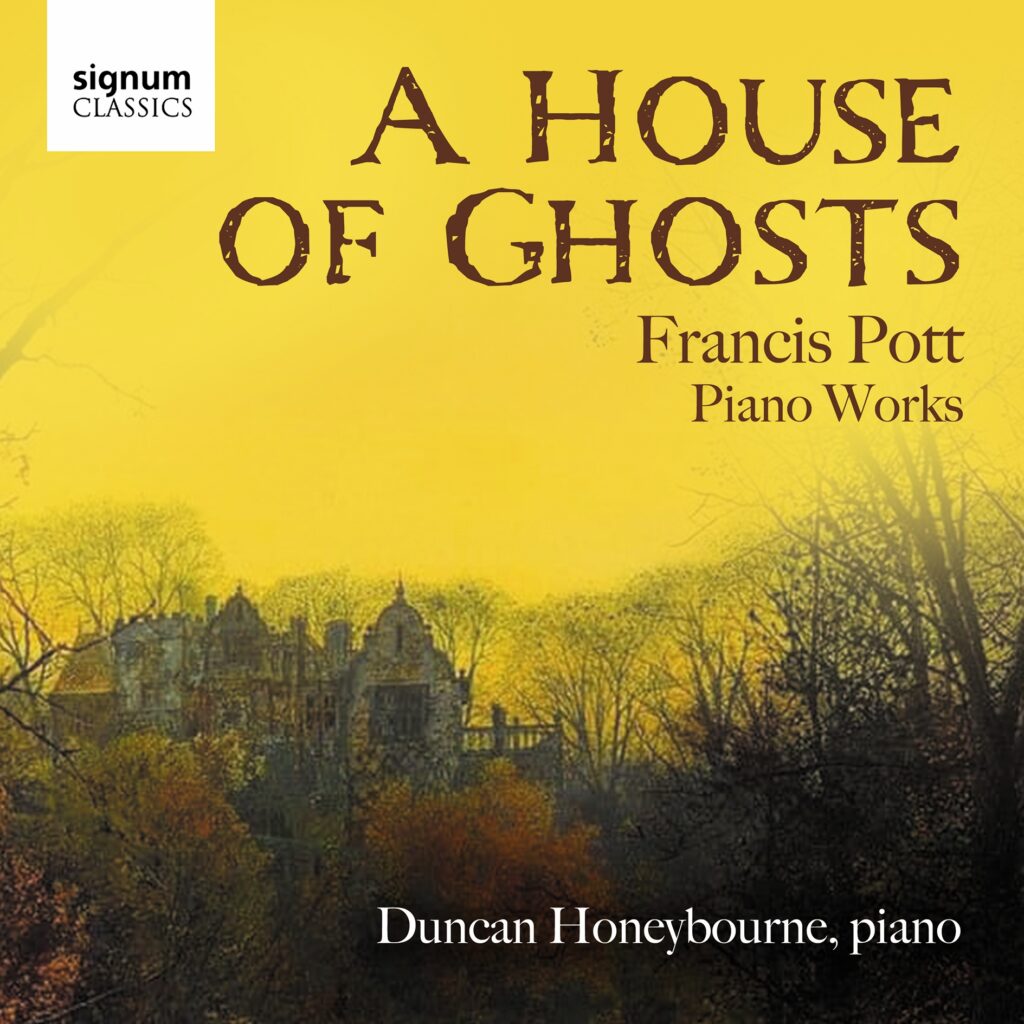

This new release of music by British composer Francis Pott, performed by Duncan Honeybourne, brings together piano works written between 1983 and 1997.

The title of the album, ‘A House of Ghosts’, reflects the character of the pieces: short works and miniatures which offer glimpses of places and voices that remain just out of reach, rather than an overall narrative. Pott’s music is elegant and restrained, reflecting on memory, landscape, and legend, occasional reference to medieval song (Minnelied, Blondel, Walsinghame), Chaucer (Pageant, with its distinctively ‘Medieval’ open fourth and fifth chords), T. S. Eliot (Revenant), and the abandoned community of St Kilda, a remote archipelago in Scotland (Farewell to Hirta). The mood of many of the pieces is wistful or nostalgic, with a timelessness which harks back to earlier times and musical styles: Pott’s influences include William Byrd, Gustav Mahler and Vaughan Williams, and one hears echoes of these composers, and others, in his harmonies, textures and long-spun melodies.

“A House of Ghosts is a sequence of a dozen short pieces concerned with the past, whether imagined, historical or (as in the case of the final piece) autobiographical. These movements are combined here with freestanding longer items, where sea music (Farewell to Hirta and Hunt’s Bay) is mixed with explorations of elusive memory (Le Temps qui n’est plus and Drowned Summer). Gently distinctive in its harmonic and tonal language, this music is the work of a professional pianist-composer with a refined and subtle insight into the physical and textural properties of the instrument.”

Duncan Honeybourne, pianist

I had the pleasure of page-turning for a performance by Duncan Honeybourne of several of the pieces featured on this album. This not only introduced me to Pott’s compelling soundworld but also offered a glimpse of his writing style. ‘A House of Ghosts’ is music written for the intimacy of the home, with the amateur pianist very much in mind. This is music that will appeal to the sophisticated amateur pianist who enjoys contemporary music that is melodic, structured and expressive, yet not overly-challenging. The music is highly pianistic (the composer is a pianist himself), approachable yet thought-provoking, consonant…. They may appear simple, but there is much scope for sensitivity in voicing, dynamics and pedalling to bring these finely-crafted pieces to life.

Duncan Honeybourne brings clarity, gracefulness and emotion to this elegant, atmospheric music, responding with much musical thought and sensitivity to its subtly-shifting colours and moods to create an album that is wholly enjoyable and deeply absorbing.

A House of Ghosts is released on digital streaming and download

Scores of Francis Pott’s music are available from Composers Edition