Guest post by Howard Smith

4 pianists, 4 passions

Two hours of piano music, accompanied by GenAI art projection and a smattering of poetry. Performers: Elena Toponogova, Ophelia Gordon, Howard Smith and Matthew Baker Music by Frank Bridge, Nikolai Medtner, Erik Satie, Francis Poulenc, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel & Nikolai Kapustin.

What’s behind our forthcoming event Personal Passions? Two years ago I had completed study of several works by Erik Satie, specifically, the Gnossiennes, the Gymnopedies and the Ogives. I had also ‘composed’ a series of short sequences to sit between the pieces. Each of these rests on the tritone from the preceding key and acts to ‘reset the ear’ prior to the following piece. This helps clarify the transition. I felt this was necessary because the beguiling pieces are similar in character. I call each of these brief improvisations an ‘hiatus’. The concept was performed in fragments at various piano meetup groups. On April 5th this year, at October Gallery, I shall perform the full sequence and will be joined by Elena Toponogova, Ophelia Gordon and Matt Baker – three wonderful pianists and friends. We shall each play for around 30 minutes.

Elena Toponogova will play ‘Forgotten Melodies’ by Frank Bridge and Nikolai Medtner.

Matthew Baker will surround us with ‘Impressionism’, playing the music of Francis Poulenc, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel.

Ophelia Gordon will introduce her forthcoming CD: KAPUSTIN – Between The Lines, to be released on the Divine Arts label later this year. Ophelia will play 30 minutes of the CD.

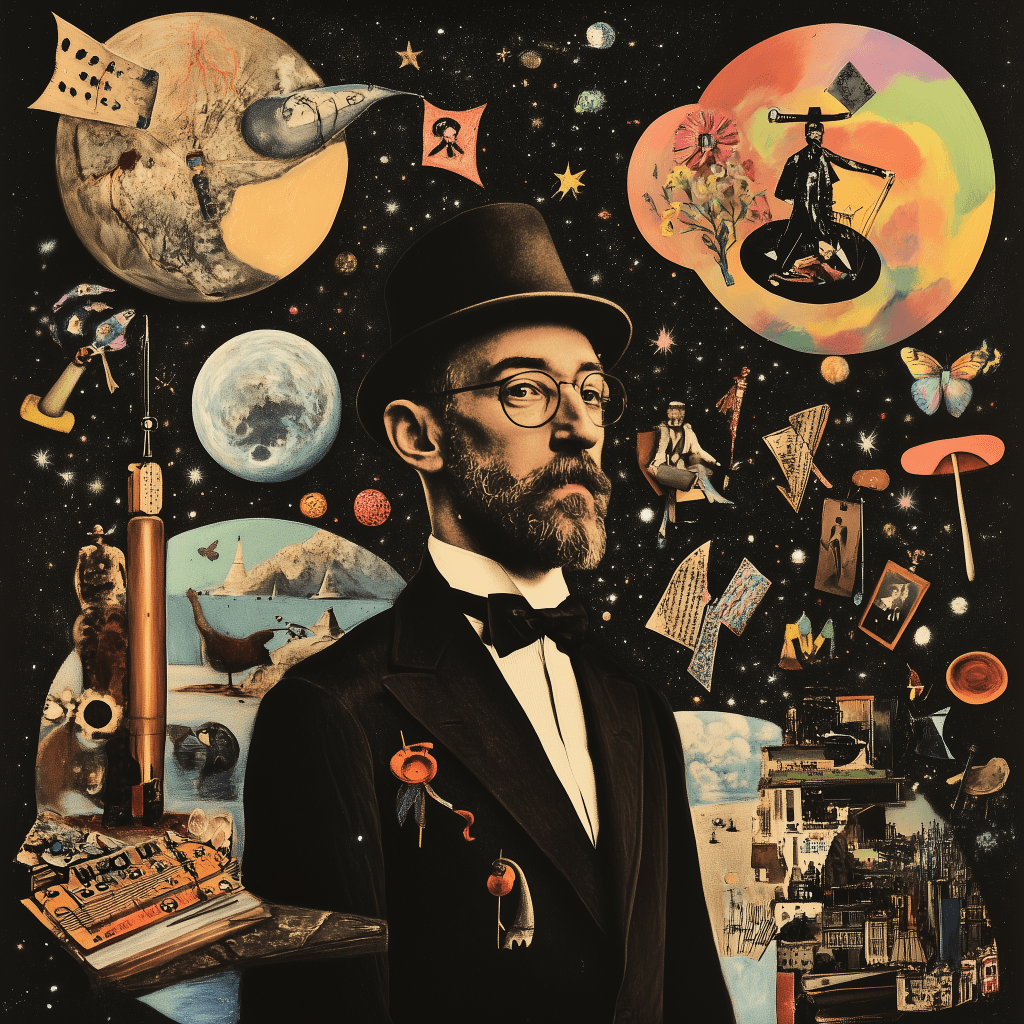

To add to the event, and based on my experience in the IT industry with GenAI (Generative Artificial Intelligence), we will be projecting sequences of images to support each of the four segments of the concert. Each has been themed around our ‘Passions’. The October Gallery space is ideal for this with its projection system and lighting.

We look forward to welcoming you to this unique venue. If successful, we hope the 4×4 format will be liked and can be repeated for other artists – both professionals and advanced amateurs from active piano circles in and around London, over the coming years. No promises but watch this space!

Event details:

Saturday 5th April 2025 at October Gallery, 24 Old Gloucester St, Bloomsbury, London, WC1N 3AL

Doors 7pm, Performances 7:30 until 10pm, 20 minute interval

Tickets £19. Book tickets at: https://billetto.co.uk/e/personal-passions-october-gallery-london-tickets-1098829

Reviews:

‘Her performance was mesmerizing!’

‘Serious, deep and rarely-performed pieces played with understanding and verve’

‘Poetic playing which draws the audience into her sound world’

‘Her captivating performance motivated me to aspire to her level. Having been a keen pianist myself in the past, I felt inspired to dive in and play the instrument again’

Programme

Satie, Erik – Gnossiennes: nos. 1 – 3

Satie, Erik – Ogive no. 1

Satie, Erik – Gymnopédies: nos. 1 – 3

Bridge, Frank – 3 Sketches, H.68

Medtner, Nikolay – Fairy Tale, Op.26 no.3

– Interval –

Poulenc, Francis – 3 Novelettes, FP 47/173

Poulenc, Francis – 8 Nocturnes, FP 56

Debussy, Claude – Ballade

Debussy, Claude – Suite Bergamasque: III, Clair de lune

Ravel, Maurice – Sonatine

Kapustin, Nikolai – programme to include the Concert Etudes, Op.40

Founded in 1979, October Gallery is a charitable trust which is supported by rental of the Gallery’s unique facilities, grants from various funding bodies and the active support of dedicated artists, musicians, writers and many friends from around the world. The Gallery promotes contemporary art from around the planet, as well as maintaining a cultural hub in central London for poets, artists, intellectuals, and hosts talks, performances and seminars.