By Michael Johnson

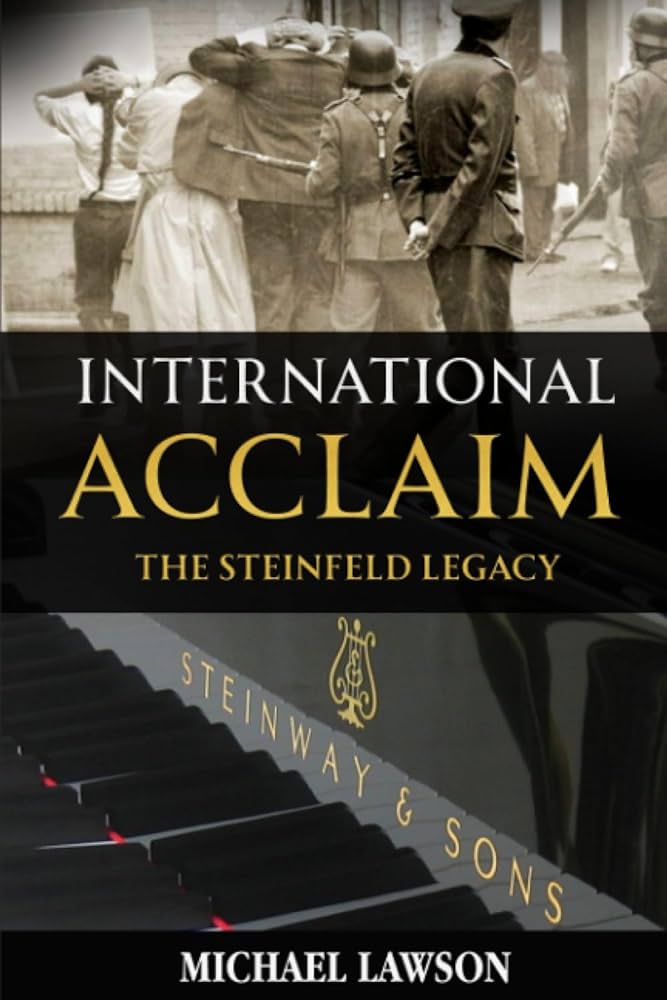

English musician and polymath Michael Lawson has established a reputation in a diversity of professions – composer, pianist, psychotherapist, documentary filmmaker and archdeacon of the Church of England. As a therapist, he has worked with a variety of individuals, ranging from child prodigies to sex offenders. His remarkable new novel, International Acclaim: The Steinfeld Legacy, is an ambitious work of ‘faction’, combining real-life giants of the Romantic music era with his family story of the “Steinfelds”—four generations of brilliant Jewish Polish concert pianists.

What drives this man? “I am definitely an enthusiast for the things I love to do,” he says in the interview below. “Does that make me a workaholic? Maybe, maybe not…. I can also be something of a sloth.”

His narrative chronicles the tumultuous story of Europe’s composers and performers through political change and wartime crises on the Continent. Leading his parade of historic figures are, among others, Alexander Siloti, Josef Hofmann, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Theodor Leschetizky, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Sergei Taneyev, Leopold Godowsky, Huw Weldon and of course Nadia Boulanger.

In response to questions that led to his novel, Lawson granted an email interview:

How long a gestation period preceded the writing of your first novel, International Acclaim?

In short, about 40 years! I had always been fascinated by the great Romantic pianists. As a teenager, I’d listen for hours, enthralled by extraordinary virtuosity which shone through the hisses and scratches of their early 78 rpm recordings. I not only amassed a huge record collection, I researched and read everything I could find about them. So initially, I didn’t know where to begiin the novel but I’d worked out how it would end— a passage inspired by the death of Simon Barere, one of the last of the late Romantics, who tragically died during his performance of the Grieg piano concerto. at Carnegie Hall in 1951.

What took you so long to write these nearly 500 pages?

The novel remained unwritten as my growing family and day job took precedence. Yet an editor’s stimulus kept the aspiration alive, and the story gradually emerged in my imagination. Yes, the process started 40 years ago. And then in 2020 came the first coronavirus lockdown. That was my opportunity. I researched and wrote non-stop for six months till International Acclaim was complete and published. After six more months thinking about it and taking advice, I began the revisions. That is how the novel came to be republished recently – with a new subtitle to celebrate it: International Acclaim: The Steinfeld Legacy.

Was this story always in the background as you proceeded with your composing, church and psychotherapy careers?

Yes, it was on a slow boil but I knew that one day its time would come. Accumulated observation has taught me so much about human life and living, which I have worked into my story of the world of musicians. And to take on these different roles in parallel has enabled me to explore the passions that I have discovered within myself. This is why I don’t normally speak of “my career in music”. Music touches a deeper passion and informs my very identity. I feel the same about my work in psychotherapy and ordination.

Isn’t this what you therapists would call a split personality?

No, the worlds are different and yet at times so complementary. A prime learning experience for me has been my work in private practice with musicians of all kinds including child prodigies. Many of these have sought help feeling the unravelling of their emotional complexity may be assisted by someone who can understand the peculiar pressures of the performing piano world. Later in my career, my seven years in the prison service meant working with broken people with exceptionally convoluted life stories. For them rehabilitation is the goal. My therapeutic aim is the same with prisoners as it is with musicians – to bring support, to unravel self-understanding and thus to alleviate suffering.

You must have been a lifelong student of music history. What was your training?

Alongside my conservatoire training at the Guildhall School of Music, and the Écoles d’Art Américaines in Fontainebleau, France, my first degree in music was at the University of Sussex. Over my lifetime, I have built up quite a library about the whole of Western music and especially the composers and pianists of the late Romantic era. Although I had no other models in mind when I wrote International Acclaim, I included real figures of history alongside my fictional Steinfeld family. Allowing for literary license, I aimed for the best verisimilitude I could imagine. Bringing in the key figures of the era helped tell the story. We meet Alexander Siloti, Theodore Leschetizky, Sergei Taneyev, Leopold Godowsky, Sir Henry Wood, Huw Weldon and others. In a class by herself is my teacher Nadia Boulanger.

Workaholism seems to be your driving force, right?

I have thought about that, and my answer is I am definitely an enthusiast for the things I love to do. Does that make me a workaholic? Maybe, maybe not. I recognise I can also be something of a sloth. It’s only then that I say with Jerome K Jerome, “I love work. It fascinates me. I can sit and look at it for hours!” It’s my family that should take the credit. They are my reason to come up regularly for air.

From the age of 8, you knew you wanted to be a composer. Wasn’t that before you had started piano?

It didn’t take long for me, as a youngster, to discover that it was more enjoyable to create tunes of my own than to play others’ compositions. Some three years before I began piano lessons, I composed a set of “Hungarian dances”. On a family vacation there was an excellent pianist who played every night in the lounge of our hotel. I noticed that he often played requests. Without consulting my parents, this rather bold 8-year-old, with Hungarian dances in hand, asked the pianist to try them out. He was very nice and said that he would look them over.

Was that the end of it?

Not at all. As my parents were sipping Asti and my sister and I were exploring the ice cream menu, I heard a tune I recognised, looked up and realised this pianist was playing my music. It was thrilling to hear it played by such a good musician. But I was resistant to the effort that piano lessons might require. Finally, I gave in and started lessons. So, yes, that’s how it worked out – composer first, and piano second.

Did this lead to something of a career as a pianist?

Yes and no. My father, in his quest to get me to learn the piano, bought me a Kazoo! I could hum away and out would come music. I loved it. A few weeks later my dad popped the question, “Wouldn’t you like to be able to make music as easily on the piano?” My time had come.

Were you some kind of late-blooming prodigy?

I may not have been a child prodigy but I was certainly like a duck to water. I fell in love with the piano, and practised all hours, seemingly night and day, and passed grade 8 (by the skin of my teeth) at only 14 months after my first lesson. At age 14, I remember playing Bartok’s loud and ferocious Allegro Barbaro in public. In the audience was David Wilde, winner of first prize in the Liszt Bartok piano competition in Budapest in 1961. David was encouragingly complementary, but frank also. If I wanted to become a concert pianist I would need to develop considerable reserves of technique. To that end, he generously took me on as a private student and for several years taught me so much about the beating heart of the music as much as the mechanics of playing.

Didn’t you mix with some of the great players?

Yes. Through David, I met conductors such as Pierre Boulez and other leading musicians. I learnt so much from observing them in rehearsal. And there was another spin-off. Around this time, while I was a student, concert organisers often asked me to turn pages for some of the world’s greatest pianists, including Artur Rubenstein, Sir Clifford Curzon, Daniel Barenboim, Vladimir Ashkenazy, and others. I also turned pages for Geoffrey Parsons when he accompanied Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, and for chamber musicians like the remarkable American pianist, Lamar Crowson.

As a music student, you were in a position to learn informally from some of the greats.

I learnt much from all of them – by closely watching their hands, asking questions about interpretation and technique, and occasionally even getting a mini-lesson in return. On one occasion I asked Sir Clifford Curzon, the perfect English gentleman, how he recommended practising the demanding octave trills in the Brahms D minor piano concerto. “I don’t know,” he said, “I just do them.” But he did know really, and he showed me – in musical slow motion. When his fingers shook, his arms and shoulders shook with them. The facility flowed from the extraordinarily looseness and relaxation of his arms and shoulders. The effect was electric.

How close were you to Nadia Boulanger?

I was fortunate indeed to have studied with Mademoiselle for five very fruitful years. That is, during the summers at Fontainebleau, and while pursuing my other studies by flying back and forth to Paris during the rest of the year. During all that time she refused to let me pay for my lessons. The list of Boulanger pupils reads like a Who’s Who of many of the greatest figures in 20th-century music. The composers include Walter Piston, Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, Virgil Thomson, Roy Harris, Philip Glass, Darius Milhaud, Jean Françaix, Thea Musgrave, Lennox Berkeley, Joseph Horovitz, and Emile Naoumoff. Her conductors include Igor Markevitch and John Eliot Gardner. She and I kept in touch until the end of her life.

Have you always considered yourself a writer?

Socially, I was quite shy. But something clicked in my brain and released all kinds of creative energy hitherto so dormant that my teachers thought was non-existent. I had been particularly poor at English. That quickly changed. I had been a poor reader but was encouraged by an older friend who had taken an interest in me. He was knowledgeable about literature and was an excellent classical pianist too. He introduced me both to novels and poetry. I began to read everything I could get my hands on. This all had an almost explosive effect on my use of language. And I began to write—words as well as music.

What was your introduction to music criticism?

By the time I went to Sussex University, I was appointed music critic of the University’s weekly newspaper. I’m not too proud of my youthful arrogance which surfaced in some barbed reviews. I admit I took some ungenerous liberties with the power of my pen. A lady in orchestral management helped me see the error in my ways, and after that I learned to be more encouraging in my writing. It was an exercise in understanding how your words are received. Eventually I was able bring all the rigour that I had learnt in composition and performance to producing regular material for sermons, script writing and presenting for the BBC Radio 2, which I did uninterrupted for 20 years. And for filmmaking and for eighteen books – so far.

International Acclaim: The Steinfeld Legacy by Michael Lawson is published by the Montpélier Press, and is available exclusively from Amazon

Website: www.international-acclaim.com

Audible version: www.audible.co.uk

Review: A Breathless Epic of the Great Romantic Pianists

MICHAEL LAWSON is a Composer, Writer, Psychotherapist, Film Maker and Broadcaster. His varied career began in music as a composer and concert pianist in the early seventies, having studied with the great French teacher, Nadia Boulanger, at the Paris and Fontainebleau conservatoires, with the British composer, Edmund Rubbra, at the Guildhall School of Music, and at Sussex University with Donald Mitchell, the leading Britten and Mahler scholar. His piano professors were the distinguished British pianists, David Wilde and James Gibb.

MICHAEL JOHNSON is a music critic and writer with a particular interest in piano. He has worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Moscow, Paris and London over his journalism career. He covered European technology for Business Week for five years, and served nine years as chief editor of International Management magazine and was chief editor of the French technology weekly 01 Informatique. He also spent four years as Moscow correspondent of The Associated Press. He is a regular contributor to International Piano magazine, and is the author of five books. Michael Johnson is based in Bordeaux, France. Besides English and French he is also fluent in Russian.