I missed Krystian Zimerman’s London concert last April when he stood in for the indisposed Mitsuko Uchida and gave what was by all accounts a remarkable performance of Schubert’s last two sonatas, works written in the dying embers of the young composer’s life yet imbued with nostalgia, warmth, an intoxicating bitter-sweetness and, ultimately, hope.

It’s rare for Zimerman to come to London; even rarer for him to release a new disc. He feels that high-quality digital recordings have created a homogeneous sound and style, robbing art music of spontaneity and leading audiences to expect perfection on disc and in concert (something I largely concur with, based on my regular concert-going). Thus, he’s very particular about what and when he records. This is his first recording of Schubert’s last two sonatas and his first solo album for a quarter of a century – and my goodness it was worth the wait! The recording was made in Japan using a Steinway with Zimerman’s own keyboard (which, incidentally, he made himself) inserted into the instrument (like the great pianists of the past, such as his mentor Arthur Rubinstein, he travels on the condition that his own instruments and/or separate, particularly-voiced keyboards accompany him, to suit the repertoire he is performing). The result is impressive, the bespoke action producing a sweetly singing tone and wonderful clarity. In the liner notes (which take the form of an interview) Zimerman explains that the special piano action “is designed to create qualities Schubert would have known in his instruments. Compared to a modern grand piano, the hammer strikes a different point of the string, enhancing the ability to sustain a singing sound…..”

But of course it’s not just the bespoke action which makes Zimerman’s sound so special. No, there is more, much more to this performance. Overall, there is an immaculate sense of pacing, so sensitive and natural; the first movement of the final sonata, for example, unfolds like a great river plotting its final course, the hymn-like first subject theme imbued with joyful purpose which gives the music forward propulsion without ever sounding hurried (it’s a leisurely mässig). In the first movement of the D959, the grandeur of the opening sentence gives way to the wistfulness and intimacy of an impromptu – and immediately Zimerman’s sense of phrasing is revelatory, shedding light on details hitherto skimmed over by others and demonstrating a complete understanding of Schubert’s architecture and narrative, both within movements and the works as a whole.

Throughout, there is subtle rubato in his contouring of phrases, thoughtful use of agogic accents to highlight intervallic relationships or strikingly piquant harmonies (so much a feature of Schubert’s late music), a Mozartian clarity in the passage work and repeated chords (for example in the development sections of both first movements) and an understanding of Schubert’s very specific rests and fermatas – attention to tiny details which create remarkable breathing spaces and enhance the structural expansiveness and improvisatory character and modernity of this music. Restrained use of the sustain pedal creates transparent textures, most notably in the slow movements: the Andantino of the D959, too often the subject of musical “psychobabble” and emotional wallowing, has a desolate gracefulness in its outer sections which contrast perfectly with the hysteria of the central “storm”. When they come, the Scherzi (both marked Allegro vivace) are light and ebullient, though Zimerman is always aware that Schubert is often more tragic when writing in the major key. In sum, every bar is carefully considered and insightful, yet at no point does this music sound fussy, overly precious or reverential. This is some of the most natural Schubert playing I have encountered and it suggests an artist with a long association with and deep affection for this music

As regular readers of this blog will know, I have spent the last three years studying and learning Schubert’s penultimate piano sonata, D959. It has become something of an obsession for me, initially forming the bulk of my programme for a Fellowship Performance Diploma and now a piece of music I simply can’t let go of. I have heard many recordings of the sonata from Schnabel and Cherkassy to Andsnes, Leonskaja and Barnatan, in addition to five live performances (including by Piers Lane, Andras Schiff, Richard Goode and mostly recently Paul Berkowitz). When one spends so much time with a single piece of music, one can grow fussy, pedantically so, about how this music is presented in concert and/or on disc – so much so that I have stopped seeking out the work in concert because I listen far too attentively and critically for my own good…..and talking of “Goode”, the one and only live performance I really enjoyed, the one which left me with the feeling that this was how Schubert would have wanted his music performed, was by the American pianist Richard Goode at the Royal Festival Hall in May 2016 (of which more here). In Krystian Zimerman I have found my new benchmark, not just for the D959 but as a demonstration of how Schubert’s piano music should be played.

Very highly recommended

Such is the spell of your emotional world that it very nearly blinds us to the greatness of your craftsmanship

– Franz Liszt on Franz Schubert

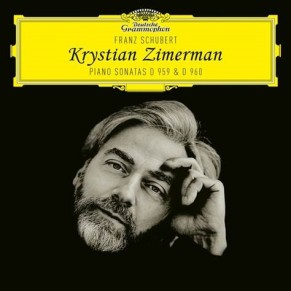

Franz Schubert/Krystian Zimerman/Piano Sonatas D 959 and D 960

Deutsche Grammophon

00028947975885

I have written my own review on my site. I haven’t yet fully made up my mind about Zimerman’s Schubert – surely the sonatas sound different in his recording. But do let us know what you think of the Impromptus: these pieces are among my favourite solo piano pieces in the piano repertoire. I was wondering if you have any favourite recordings of the Impromptus or whether you would like to discuss this in another post!

I look forward to listening to Zimerman’s Impromptus. I do like Murray Perahia in these pieces and also Maria Joao Pires.

A really great review! You really bring across your passion for these amazing works (which I full share). As mentioned previously in my review, I´m still somehow struggling with this performance (at a very high level obviously), but I will make sure to revisit in on a regular basis. Zimerman has surely prepared this for years, so it clearly is a statement not to be ignored.

Thank you – I do love this music and so I was delighted to find in Zimerman an approach to Schubert’s piano music which chimes with my own. I’m going to listen to his recording of the Impromptus next 🙂