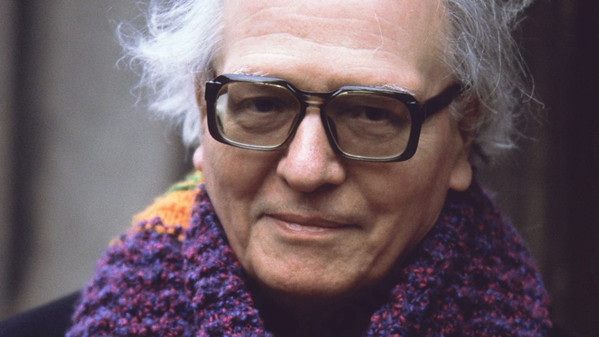

Olivier Messiaen is widely regarded as one of the most important composers of the 20th century, known for his unique approach to harmony, rhythm, and melody. His music is challenging for any performer, requiring not only technical skill, but also a deep understanding of his unique musical language.

The pianists presented here demonstrate a remarkable ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s music, bringing out its intricate harmonies, colours, textures and rhythms, as well as its emotional depth.

Yvonne Loriod

Messiaen’s student, muse and second wife, Yvonne Loriod was a highly accomplished pianist in her own right. Many of his piano works were written with her in mind. The Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus (“Twenty Contemplations on the Infant Jesus”) were dedicated to Loriod, and she premiered the work at the Salle Gaveau in Paris in March 1945. Loriod’s playing is known for its clarity and precision, as well as her ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s unique style. She recorded several albums of Messiaen’s piano music, including the complete set of Preludes and the Catalogue d’Oiseaux.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard

French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard is widely recognized as one of the foremost interpreters of Messiaen’s music. Aimard’s connection to Messiaen’s work runs deep, as he was a student of the composer and worked closely with him and his wife Yvonne Loriod. Aimard’s recordings of Messiaen’s piano music are considered some of the most authoritative, and he has performed Messiaen’s works all over the world to critical acclaim.

Angela Hewitt

Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt is perhaps best known for her interpretations of Baroque and Classical music, but she has also made a name for herself in more contemporary repertoire, including Messiaen’s piano music. Her recordings of Messiaen’s music are admired for their technical precision and attention to detail, as well as her ability to bring out the emotional depth of the music.

Steven Osborne

Scottish pianist Steven Osborne has performed Messiaen’s music all over the world, including the Vingt regards and Turangâlila Symphonie. Osborne expertly navigates the intricate harmonies and rhythms in Messiaen’s music with ease, bringing out the complex textures and polyrhythms that are hallmarks of the composer’s style. At the same time, he captures the emotional breadth and spiritual intensity that are crucial features of Messiaen’s music. His performances of the Vingt regards in particular are extraordinarily absorbing, meditative and moving, combining musicality, virtuosity and commitment. (I’ve heard Osborne perform this monumental work twice in London and on both occasions it has been utterly mesmerising and profoundly emotional.)

Tal Walker

For his debut disc, the young Israeli-Belgian pianist Tal Walker included Messiaen’s Eight Preludes. Composed in the 1920s, they are clearly influenced by Debussy with their unresolved or ambiguous, veiled harmonies and parallel chords which are used for pianistic colour and timbre rather than definite harmonic progression. But the Preludes are also mystical rather than purely impressionistic, and look forward to Messiaen’s profoundly spiritual later piano works, Visions de l’Amen (for 2 pianos) and the Vingt regards. Tal Walker displays a rare sensitivity towards this music and his performance is tasteful, restrained yet full of colour, lyricism and musical intelligence.

Other Messiaen pianists to explore: Tamara Stefanovic, Peter Hill, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Ralph van Raat, Benjamin Frith, Peter Donohoe

This article first appeared on InterludeHK

Olivier Messiaen is widely regarded as one of the most important composers of the 20th century, known for his unique approach to harmony, rhythm, and melody. His music is challenging for any performer, requiring not only technical skill, but also a deep understanding of his unique musical language.

The pianists presented here demonstrate a remarkable ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s music, bringing out its intricate harmonies, colours, textures and rhythms, as well as its emotional depth.

Yvonne Loriod

Messiaen’s student, muse and second wife, Yvonne Loriod was a highly accomplished pianist in her own right. Many of his piano works were written with her in mind. The Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus (“Twenty Contemplations on the Infant Jesus”) were dedicated to Loriod, and she premiered the work at the Salle Gaveau in Paris in March 1945. Loriod’s playing is known for its clarity and precision, as well as her ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s unique style. She recorded several albums of Messiaen’s piano music, including the complete set of Preludes and the Catalogue d’Oiseaux.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard

French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard is widely recognized as one of the foremost interpreters of Messiaen’s music. Aimard’s connection to Messiaen’s work runs deep, as he was a student of the composer and worked closely with him and his wife Yvonne Loriod. Aimard’s recordings of Messiaen’s piano music are considered some of the most authoritative, and he has performed Messiaen’s works all over the world to critical acclaim.

Angela Hewitt

Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt is perhaps best known for her interpretations of Baroque and Classical music, but she has also made a name for herself in more contemporary repertoire, including Messiaen’s piano music. Her recordings of Messiaen’s music are admired for their technical precision and attention to detail, as well as her ability to bring out the emotional depth of the music.

Steven Osborne

Scottish pianist Steven Osborne has performed Messiaen’s music all over the world, including the Vingt regards and Turangâlila Symphonie. Osborne expertly navigates the intricate harmonies and rhythms in Messiaen’s music with ease, bringing out the complex textures and polyrhythms that are hallmarks of the composer’s style. At the same time, he captures the emotional breadth and spiritual intensity that are crucial features of Messiaen’s music. His performances of the Vingt regards in particular are extraordinarily absorbing, meditative and moving, combining musicality, virtuosity and commitment. (I’ve heard Osborne perform this monumental work twice in London and on both occasions it has been utterly mesmerising and profoundly emotional.)

Tal Walker

For his debut disc, the young Israeli-Belgian pianist Tal Walker included Messiaen’s Eight Preludes. Composed in the 1920s, they are clearly influenced by Debussy with their unresolved or ambiguous, veiled harmonies and parallel chords which are used for pianistic colour and timbre rather than definite harmonic progression. But the Preludes are also mystical rather than purely impressionistic, and look forward to Messiaen’s profoundly spiritual later piano works, Visions de l’Amen (for 2 pianos) and the Vingt regards. Tal Walker displays a rare sensitivity towards this music and his performance is tasteful, restrained yet full of colour, lyricism and musical intelligence.

Other Messiaen pianists to explore: Tamara Stefanovic, Peter Hill, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Ralph van Raat, Benjamin Frith, Peter Donohoe

This article first appeared on InterludeHK

This site is free to access and ad-free, and takes many hours to research, write, and maintain. If you find joy and value in what I do, why not