by Michael Johnson

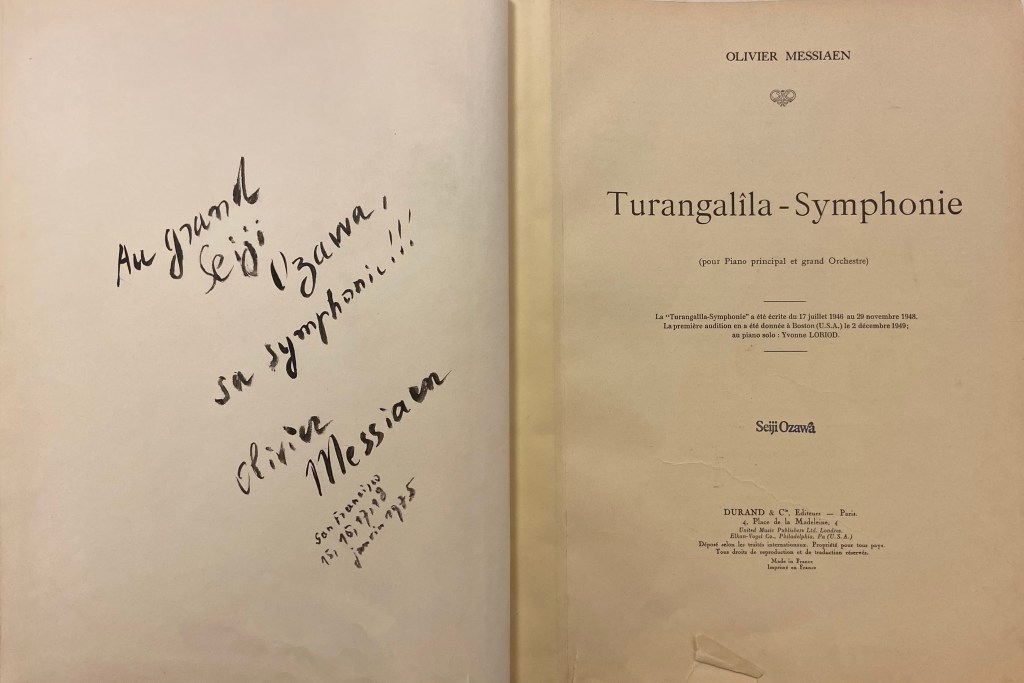

Of all the musical jewels Olivier Messiaen left us, his Turangalîla-symphonie is most commonly associated with him. It is not a symphony in any traditional sense but rather a mosaic of ten movements that unfolds over an hour and twenty minutes. One critic jocularly characterized it as replete with “dancing rhythms, tantric sex and laughing gas”. Messiaen called it “superhuman, overflowing, dazzling and an exercise in abandonment”.

In this complete version, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel with Yuja Wang at the piano, the drama and the abandonment are among the best of many recordings.

Next year marks the 80th anniversary of Messiaen’s two-year struggle to hold all the disparate elements of this masterpiece together.

His prolific output seems sure to survive in the volcanic world of contemporary composition. His balance of originality and accessibility makes him popular with concert-goers and objects of interest to the wider music world. His controversies have faded with time, but his theology, birdsong and synesthesia serve his memory well. He has left a strong imprint on the world of modern music.

His mysteries and controversies continue to attract music sleuths. Did Pierre Boulez really say Messiaen’s music made him want to vomit? Scholars have been trying to track down that unkind cut for decades but details remain clouded. Boulez has denied that he ever used the word. Others say he did. His objection to Messiaen was his use of the ondes Martinot in some of his works, most spectacularly in Turangalîla.

Pianist Peter Hill, an English scholar and Messiaen specialist, tells me in an email exchange that he “skirted the (Boulez) issue cautiously” in his 2007 book Messiaen because he was not satisfied he had nailed it. The wording he came up with was that Boulez could be “almost offensively derogatory” about Messiaen although he could also be an admirer. How Boulez was so conflicted continues to intrigue musicologists. Messiaen’s widow and primary performer of his piano works, Yvonne Loriod, told Hill a few years ago that Boulez was “very hot-headed” and recalled that he made some deeply wounding remarks backstage to Messiaen after a rehearsal of Turangalîla in 1948.

Messiaen acknowledged that the music establishment found the twittering of birdsong in his compositions to be misplaced. “It makes them (his critics) laugh, and they don’t hold back,” he acknowleged in an interview. His widow later recalled that his music always faced a mixed reception during his lifetime. “He would sometimes win the admiration of the public but the critics could be very, very spiteful,” she said. And he was pilloried by the atonal elite for not being far enough avant the garde.

Even today, I keep running into Messiaen-lovers. One French woman who as a child heard Messiaen play the Sainte Trinité (Holy Trinity) organ in Paris. She tells me his playing could be “grandiose, almost frightening”. Messiaen took a liking to her and invited her one day to sit at the organ. She still remembers touching a few keys. “He smiled when I put a shy finger on the keyboard, then he struck the first majestic chords of the Bach Toccata and Fugue. The church was flooded with waves of that gigantic sound. I carry it with me these many years later.”

Controversy aside, Messiaen’s place in music history is assured today, with some music scholars ranking him alongside Stravinsky as one of the most innovative voices of his time. Major works were commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and he was in demand worldwide for teaching harmony and composition.

He became a virtual rock star in Japan, where he discovered Japanese traditional music and borrowed from the harmonics he was hearing there for the first time. A mountain peak near Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, was named “Mount Messiaen” in 1976 in homage to his orchestral suite Des canyons aux étoiles. A handful of his works remain in the standard repertoire but there is much more Messiaen that is rarely played. A closer investigation reveals a unique sound world, much of it inspired by birdsong. He left a legacy of more than a hundred works for piano, orchestra, chamber groups, solo instruments, many enhanced by electronic instrumentation and a gathering of exotic bells, gongs and cymbals and Balinese gamelans he collected from around the world.

Messiaen’s friendly manner also left good memories among those who studied with him. He laughed easily and had a taste for loud shirts toward the end of his life. His relaxed attitude toward students was to let them grow naturally, not to force them into traditions or trends. Loriod recalls her long marriage to him as passing “with never a cross word.” She has also said that she was kept at arm’s-length from his creative process. She was never informed of his works in progress, she said, and was only allowed to study and play the works when completed.

Messiaen’s circle as a popular Paris Conservatoire professor included students Boulez, Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, Harrison Birtwhistle, Alexander Goehr, George Benjamin, Tristan Murail and Gérard Grisey, among others who went on to push the avant-garde boundaries. Boulez, writing in The Messiaen Companion, credited Messiaen with “the great merit of having freed French music from that narrow and nervous ‘good taste’ inherited from illustrious forebears …”

Internment and forced isolation from the rambunctious Paris creative scene during World War II may well have enabled the birth of one of the most original chamber works of the 20th century. Messiaen produced his famous quartet virtually under German orders. “You are a composer. Then compose,” the main guard told him shortly after he was settled in. He was given private quarters, manuscript paper, pencils and erasers, and he set to work. After months of concentration on his ideas, the intensive rehearsal time snatched between work details, Quartet for the End of Time was premiered in January 1941 in the prison camp before a packed barracks. “The first difficulty was to read the piece,” recalled violinist Jean Le Boulaire. “The second was to play it together. That wasn’t easy … We had run across something we had never seen before.”

The smartly uniformed German officers of the camp occupied the front row, probably perplexed by the other-worldly sounds of the composition. Most of the audience was no better equipped to appreciate it but as a relief from camp routine it was warmly welcomed. Even today, parts of the Quartet can be hard going. Messiaen tended to think, compose and speak in synesthesia colors. He once described the sound he sought as “orange veined with violet”. Birds chirp throughout, some on the piano, some on the violin. In the fifth movement, “The Ethereal Sounds of Dreams.” an ostinato of orange-blue is superimposed on cascades of violet-purple. And the climactic eighth movement ends in a melodic second theme of orange-green.

One of my musician friends in Bordeaux says it took him ten years to grasp the piece. Now it is one of his favorites. Typically, Messiaen was less than forthcoming on some details. He often told interviewers that 3,000 prisoners attended the premiere. Some writers put the number at 4,000, or 5,000 and even 30,000. One researcher posits 350-400, sensibly basing her estimate on the capacity of the room in which it was performed. The title of the Quartet refers to the biblical passages in Revelation 10.1-7 in which an angel descends from heaven and declares that “there shall be no more time” – meaning eternity will arrive, with no past and no future to distract us from God.

A large proportion of scholarly study has gone into Messiaen’s romance with birdsong. He once said he believed birds are “the best musicians on the planet,” and credits them with inventing the chromatic and diatonic scales, and engaging in the first group improvisation in their “dawn chorus”. He would spend nights in haystacks or barns to hear it. “I simply write what I hear, then adapt it for our modern instruments,” he once said.

Birds chirp two or three octaves above piano range and some sing in quarter-tones, he said. These qualities cannot be reproduced on a standard piano but Messiaen does a fair imitation with high-register piano writing. In teaching his classes, he liked to whistle bird calls before demonstrating his piano variations.

I spent the summer listening to 16 CDs in one of Messiaen’s boxed sets and never quite fell into a trance but can now fully appreciate his extraordinary richness. One of many interesting pieces I discovered, his 1963 Colours of the Celestial City, combines all of his principal musical motifs – Christian symbolism, plainsong, birdsong, rhythm and his colour associations with musical chords. It stakes a claim to colour composition, a style he clung to for the rest of his life. Messiaen was distressed when sceptics refused to accept his mental colorations as basic to his compositions despite his precise descriptions of the vivid orange, greens and purples he saw in his mind. “I see colours whenever I hear music, and they see nothing, nothing at all. That’s terrible. And they don’t even believe me,” he said to German interviewer

The concept of orchestral use of keyboard instruments extended to his piano writing as well in which he exploited the instrument’s timbre to the full, writes Robert Sherlaw Johnson in his 1975 book Messiaen. The composer’s piano output is voluminous, with Catalogue of Birds generally noted as his most important piece. Peter Hill, in an essay on the piano music, called Messiaen’s piano writing “the equal of any twentieth-century composer in scale and scope, and arguably without parallel in the originality of its technique”. Hill, who has recorded the complete piano works, remarked to Loriod in a private interview that he considered two piano compositions, Four Studies of Rhythm and Cantéyodjaya (a name borrowed from southern India), “very important works”. She replied that the study was in reaction to serial composition which Messiaen believed was too concerned with pitch and not enough to rhythm. He didn’t like Cantéyodjaya much, she added, “but it’s certainly fun to play”. A recent recording by respected German pianist Stefan Schleiermacher brings bounce to the writing and displays Messiaen at his playful, whimsical peak, at least in piano composition. But “fun to play”? Only for the most accomplished players.

Messiaen died after surgery at the Beaujon Hospital in Paris April 29, 1992. After his funeral, Yvonne Loriod ordered a special gravestone topped with the sculpture of a bird.

Michael Johnson is a music critic and writer with a particular interest in piano. He has worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Moscow, Paris and London over his journalism career. He covered European technology for Business Week for five years, and served nine years as chief editor of International Management magazine and was chief editor of the French technology weekly 01 Informatique. He also spent four years as Moscow correspondent of The Associated Press. He has been a regular contributor to International Piano magazine, and is the author of five books. He also writes for this sites sister site ArtMuseLondon.com. Michael Johnson is based in Bordeaux, France. Besides English and French he is also fluent in Russian.