The impulse to complete an unfinished work by a composer such as Schubert arises from a blend of artistic curiosity, historical empathy and creative challenge. For many musicians and scholars, an incomplete score feels like a fragment of a larger, untold story – and one that invites further exploration. Incomplete music, such as Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony or the Sonata in F-sharp minor, D571, give tantalising glimpses of musical ideas that may reach to something beyond their surviving pages. To engage with them is to enter a conversation with Schubert’s imagination: reconstructing, interpreting and attempting to extend his thoughts with respect and insight.

Scholars and musicians often study sketches, harmonic trajectories and stylistic patterns to infer how the composer might have continued. For some, this process is an act of homage – an attempt to illuminate what time or circumstance denied completion. For others, it’s an opportunity to test one’s own understanding of the composer’s musical voice and logic, a kind of creative empathy that bridges scholarship and performance.

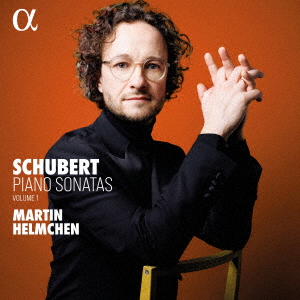

In the first instalment of his complete recording of Schubert’s piano sonatas, German pianist Martin Helmchen offers his completion of the fragmentary Sonata in F-sharp minor, D571.

Only the first movement of this work exists, and that was abandoned by the composer before it was completed. This is not the first time someone has attempted to complete this unfinished work: pianists including Paul Badura-Skoda, Malcolm Bilson, and Martino Tirimo have sought to realise Schubert’s assumed intentions, drawing hypothetical completions of the music from such separately published pieces as the piece (usually assumed to be an Andante) in A major, D604, and the Allegro vivace in D major and Allegro in F-sharp minor, D570. The question that this sonata poses – and indeed the other fragmentary sonatas by Schubert – is did Schubert stop composing simply because he ran out of time or inclination, or did not have enough money to buy music manuscript paper? But incomplete doesn’t mean insignificant, and Helmchen, clearly appreciating the significance of the fragment of D571 (it is, after all, a very beautiful piece of music), has completed these movements with great care and understanding, inspired by the recordings and the analyses of Paul Badura-Skoda.

On this recording, we now have a complete Sonata D571, scored in four movements, its wistful, almost surreal opening movement – completed by Helmchen – giving way to an elegant, lyrical Andante, a suitably playful Scherzo, and a dramatic rondo finale, also completed by Helmchen, which feels “wholly Schubert” with its shifting harmonies, contrasting textures and moods, and a radiant middle section which briefly recalls the opening movement in its poignancy. The overall result of this completion is convincing rather than speculative, – ‘proper’ music by a musician – due in no small part to Helmchen’s affinity with the music of Schubert in general (listen to the rest of the disc for a full appreciation of Helmchen’s sensitive Schubert playing). He plays with great maturity, alert to Schubert’s shifting soundworld and innate intimacy, even in the more extrovert movements or passages, and his natural pacing, supple phrasing and clear tone never get in the way of the music. This release, recorded on a modern Bösendorfer 280, with an alluring singing tone, is the first in a series of recordings by Martin Helmchen to mark the 200th anniversary of Schubert’s death in 2028.

Martin Helmchen’s Schubert Sonatas Volume 1 is released on the Alpha Classics label on CD and streaming

Header image: Facsimile of the autograph manuscript of Schubert’s Sonata in G major D894 (British Library)

Piano Sonatas D664, 769a & 894 – Stephen Hough (piano). Hyperion, 2022

Piano Sonatas D664, 769a & 894 – Stephen Hough (piano). Hyperion, 2022 Schubert isn’t a showy composer, and nor is Uchida a showy performer. For this concert, she was dressed soberly in a dark fluid trouser suit, but there was a glint of showiness in her footwear – the most elegant silver shoes which lent a roccoco flair. Of course, the superb camera work allowed one to enjoy such details: to get up close and personal with the performer as the camera lighted on her hands and face, revealing myriad expressions, often unconscious, and which perhaps offered a glimpse to the personality beyond the notes.

Schubert isn’t a showy composer, and nor is Uchida a showy performer. For this concert, she was dressed soberly in a dark fluid trouser suit, but there was a glint of showiness in her footwear – the most elegant silver shoes which lent a roccoco flair. Of course, the superb camera work allowed one to enjoy such details: to get up close and personal with the performer as the camera lighted on her hands and face, revealing myriad expressions, often unconscious, and which perhaps offered a glimpse to the personality beyond the notes.