Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) is surely one of the greatest – if not the greatest – composers for the piano in the history of the instrument.

It probably helped that Rachmaninov was an extraordinarily talented pianist himself and the instrument dominated his creative thinking from the outset. He began playing the piano at a young age and by his early teens he was already performing in public. He went on to study at the Moscow Conservatory, where he received a rigorous musical education that included extensive training in piano performance. This background gave him a deep understanding of the instrument, both technically and artistically, which is clearly reflected in his piano music.

As a master of the piano, who fully understood its capabilities, one of the hallmarks of Rachmaninov’s piano music is its virtuosity. His music is technically demanding and requires exceptional skill and dexterity to perform. But he was also careful to ensure that his virtuosity always served the music, rather than being an end in itself, and his works for piano – from the miniatures and salon pieces to the great piano concertos – are not just impressive displays of technical prowess, but also deeply expressive and emotionally evocative, full of brooding passion that remained a powerful force in his music throughout his compositional life. His music is often intimate and personal. He wrote many of his pieces as a way of processing his own emotions and life experiences. His pieces are full of passion, nostalgia, and a sense of yearning; they plumb the depths and scale the heights of emotion, and they speak of and to the human experience in a way that is both universal and also highly intimate.

Another important aspect of Rachmaninov’s music is his use of harmony. Reacting against the trend towards modernism and the avant-garde, which dominated classical music at the turn of the 20th century, Rachmaninov remained true to the late Romantic style of which he was a master. His music is replete with lush harmonies and emotional expressiveness, and he used a wide range of complex chords and sweeping arpeggios to create a sense of richness, vivid colours, depth and emotional power.

He also had a wonderful gift for melody, and his piano pieces are full of beautiful, memorable themes which are often developed over the course of the piece, becoming more complex and intricate as the music unfolds to create a sense of narrative and emotional progression.

For the advanced amateur, and even the professional, his music can be daunting. Many pianists believe they cannot play Rachmaninov’s music because of the physical demands it places on the player – a misconception to which I subscribed for a long time, until I decided to include two of the Op. 33 Etudes-Tableaux in one of my performance diploma programmes.

I believed my hands were too small for Rachmaninov, that I didn’t have a big enough hand stretch (a ninth, at a stretch; Rachmaninov could famously stretch an octave plus 4) or the necessary power and stamina to manage the big, hand-filling chords or the tempi. So what did I do? I selected a piece (op. 33, No. 7) which included both of these challenges – and I rose to them, with the help of my then teacher who showed me that one needs neither hands like shovels nor a specially-adapted piano keyboard to play this magnificent music.

Yes, technique is crucial in mastering Rachmaninov’s music, but perhaps the harder aspect is interpretation – and for that one can hear the master himself playing his own music. Recordings of Rachmaninov playing Rachmaninov offer some remarkable insights into his approach to tempo, phrasing, dynamics, interpretation, a gift for counterpoint, and so much more. There is much expressive freedom in his performances coupled with a profound emotionality (as opposed to sentimentality), rendered with great clarity and drama. He offers us the best interpretation possible of his own music. It is therefore surprising to learn that Rachmaninov declared, “I can’t play my own compositions.”

His most famous works for piano are surely the second and third piano concertos, the Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini, and the Preludes in C-sharp minor and G minor. But his oeuvre for piano is extensive and varied – the opp. 23 and 32 Preludes, two sets of Études-Tableaux (opp. 33 and 39), transcriptions, salon pieces like the Morceaux de fantaisie and Moments musicaux, the Symphonic Dances, works for four and six hands piano, variations (on themes by Chopin and Corelli), two piano sonatas, and many other miniatures and shorter works.

Which pianists should we turn to for inspiration in this remarkable repertoire? Of today’s pianists, Evgeny Kissin is, for me, one of the finest Rachmaninov players – an opinion which was fully reconfirmed when I heard Kissin in concert at the Barbican in March; the second half was all Rachmaninov (to mark the composer’s 150th anniversary). Kissin’s technical virtuosity and musical understanding allow him to reveal the full range of Rachmaninov’s music, from hauntingly beautiful, intimate melodies to thunderous climaxes.

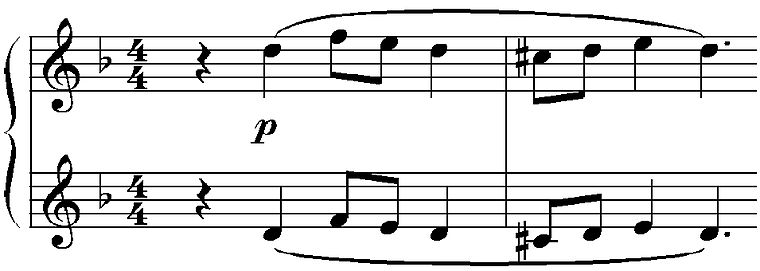

This Etude-Tableaux, from the Op. 39 set, is one of my favourites:

When preparing for my diploma, John Lill’s recording of the Etudes-Tableaux was one to which I returned many times, but I also very much like Nikolai Lugansky in this repertoire. His performances of Rachmaninov’s music in general are marked by a rare combination of technical mastery, emotional breadth, and interpretive insight which showcase the full range of the composer’s vision. Steven Osborne is another pianist whose recording of the Etudes-Tableaux I much admire for its clarity, multi-hued dynamic palette and beautiful quality of sound, coupled with a thrilling “in the moment” spontaneity.

Pianists from an earlier era must surely include Vladimir Horowitz, who was greatly admired by the composer himself, and who helped bring the third piano concerto to prominence in the USA. His recordings of the Prelude in C-sharp minor and the Vocalise in particular are also widely admired for their emotional intensity and technical brilliance.

And no collection of favourite Rachmaninov recordings should be without Sviatoslav Richter. Renowned for his technical command and expressive power, and his ability to create a sense of “controlled risk”, Richter’s performances of Rachmaninov’s music are considered some of the finest ever recorded.

Other pianists to seek out in this repertoire include Emil Gilels, Cyril Smith, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Yefim Bronfman, Byron Janis, Martha Argerich, Arcadi Volodos, Daniil Trifonov, Yuja Wang, Peter Donohoe, Khatia Buniatishvili, Valentina Lisitsa….. Each of these pianists brings their own distinct interpretive style to Rachmaninov’s music, resulting in memorable performances that are technically fluent and emotionally rich.

Up, up in the highest echelons of the pianistic pantheon sits Sergei Rachmaninov….

Up, up in the highest echelons of the pianistic pantheon sits Sergei Rachmaninov….