Impostor syndrome (also spelled imposter syndrome, also known as impostor phenomenon or fraud syndrome) is a term coined in the 1970s by psychologists and researchers to informally describe people who are unable to internalize their accomplishments. Despite external evidence of their competence, those exhibiting the syndrome remain convinced that they are frauds and do not deserve the success they have achieved. Proof of success is dismissed as luck, timing, or as a result of deceiving others into thinking they are more intelligent and competent than they believe themselves to be. Notably, impostor syndrome is particularly common among high-achieving women, although some studies indicate that both genders may be affected in equal numbers. (Source: Wikipedia)

There’s a wealth of knowledge out there to be explored, absorbed, considered and acted upon. Sometimes it can fee like a whole lifetime would never be enough to take in a tiny fraction of the information which is flung at us every second of the day.

As our circle of knowledge expands, so does the circumference of darkness surrounding it.

― Albert Einstein

I have days when I think I don’t know anything, or when I feel that I will soon be “found out”, revealed as a fraud and impostor, that I am not really a pianist or piano teacher, just someone acting out the role.

Such feelings of inadequacy are very common – and understandable, given the way we are bombarded with messages about how we should develop, be smarter, be more attractive, have more and better sex, be slimmer, eat the right food, take more exercise, be confident, have self-belief. Is it any wonder that sometimes we feel totally overwhelmed by information? Sifting through all these conflicting messages to find the ones which are relevant to us can be a Sisyphean task. Then there are peers, friends and colleagues who urge us to do this, see that, try this, think that…. Some days I just want to withdraw and become a “piano hermit”, to shut out all the noise.

At every turn, there is some kind of resource which could be useful or beneficial to our development. These may be books and journals, websites or online groups and forums where people can meet to exchange ideas. I have enjoyed lively exchanges in such online groups (notably on Facebook) and I enjoy the fact that people are willing to share information and knowledge via this medium. But I have also found such groups detrimental: observing what others are doing, or comparing oneself to others is not the best way to assess one’s abilities, progress and development, especially if these groups become a vehicle for some else to parade students’ exam successes, or seek endorsement from group members for their own achievements. Such parading of egos or mutual appreciation can make others feel inadequate.

A healthy way to move on from such feelings of inadequacy is to accept that one is at the tip of the iceberg in terms of knowledge. This should not be regarded as something negative, but rather the spur to encourage one to be inquisitive, questioning and always open to new ideas. Learning requires and encourages humility: one should be willing to accept there are different ways of doing things, or alternative ways to develop the same skills. Many teachers, myself included, engage in continuing professional development (CPD) as a more formal way of enhancing and broadening our knowledge. This may involve attending courses or workshops, being mentored by another teacher, reading, studying and interacting with others in the profession. I don’t believe we should ever stand still as teachers, or rest on the laurels of students’ achievements such as exam successes, for this attitude can breed complacency. By all means look at what others are doing, consider suggestions and ideas which are put to us and choose to embrace or reject them as we see fit.

Fundamentally, I know I am good at what I do and that I deserve to be respected (and paid appropriately) for my knowledge and skill. I do not need to measure my own success against other people’s achievements because I have confidence and self-belief in my own abilities. My students return each week for lessons which they seem to enjoy. I see them progressing and I show them ways to measure their own success (and I don’t mean through exam results, which can be useful benchmarks, nothing more). Over the decade in which I have been teaching, I’ve realised that confidently carving one’s own course leads to a greater sense of personal fulfilment and job satisfaction. In recent years, I’ve made significant changes to my teaching studio, including reducing the number of students I teach (to allow me more time to pursue my own musical studies), being selective about which students I take (I do not teach beginners or very young children, for example), and setting my fees at a rate which I feel reflects my experience. Consequently, I enjoy my teaching a great deal more and I am sure that this benefits my students too. I also find I am treated with more respect by clients, prospective clients and colleagues. I do not believe we should shy away from this kind of “self care” to enable us to do our job well, with passion and commitment.

Here’s a comment on this subject from another teaching colleague:

Despite the fact that I’ve undertaken much professional development over the past few years, I feel more aware of my shortcomings as a teacher than ever before. Rationally, I know that not to be true – my students enjoy their lessons, play well and do well in exams. But the more I learn the more I really do realise how much I still have to learn and how vast the area of knowledge is in relation to piano teaching. I find the internet a really double-edged world in all of this. On one hand it is a fantastic source of support and inspiration and I have met many wonderful colleagues online and learnt loads from them. On the other hand, scrolling through various piano teaching forums can lead me to a pit of despair as it seems as if everyone else is more experienced, knowledgeable and creative than me! So I find it’s important to keep a balanced view, be specific and targetted about my use of online forums and continue to remind myself that I’m doing my best, learning all the time and – most importantly – my students are happy and keep coming back!!

****

As a practicing musician, feelings of inadequacy always lurk at the fringes of my consciousness – and my many conversations and interviews with other musicians confirm that I am absolutely not alone in feeling this. Despite the physical proof of my abilities (two performance diplomas in quick succession and positive endorsements from pianist colleagues and mentors), I often feel a fraud. In fact, I think this feeling is helpful, for it enables me to remain humble, an important attribute for a musician, in my opinion.

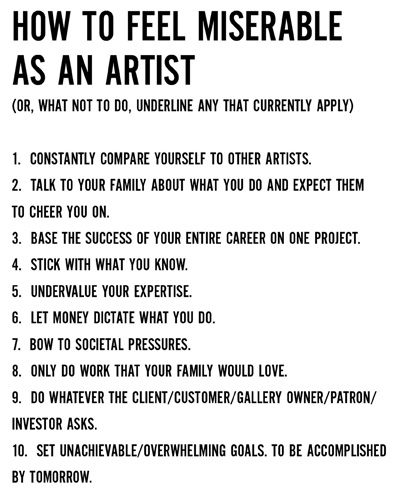

Awhile ago, I stumbled across this list, which seemed to me to encapsulate many of the things that can create and fuel feelings of inadequacy:

Turn each of these points around, and one has a manifesto by which to work and develop as a musician which is both realistic and achievable, and ensures the necessary self-compassion to allow us to flourish within our own comfort zone.

Of course whenever we open a new score, the sense of how little one knows, at that point (regardless of one’s knowledge of the composer or genre of the piece), is palpable, and when one truly cares about something, one’s standards are set very high.

The pianist Adele Marcus once said “The older I get the more I disdain the intellect.” As a colleague of mine stated, “I think that means that we become closer to the music instinctively, rather than by how we think it should sound based on knowledge of the music, the composers and history” (JB). Such a state of being can be hard won, and may take many years of study, hard graft and living with the music. Humility before the music and the composer is important; also a sense of continual striving, that one is on a journey. Sure, read the books, do the research, understand the social and historical context in which the music was created, but there must also come a point where we step away from the intellectual and the academic and liberate our personal creative impulse to “make music”

Further reading:

Music is the only field of study that requires regular and extended one-on-one interaction between student and teacher. The student-teacher relationship is a very special one, based on mutual trust and respect. Young students are often hungry for knowledge and experience: they turn to their teachers for support and advice, they share their insecurities and emotions. Music is all about expressing emotions, plumbing the depths of the soul or soaring in ecstasy, and a certain vulnerability and emotional intelligence is essential if the musician is going to communicate with honesty and passion. Good teachers know this – they encourage their students to know this too, enabling them to let go and free their spirit to play with feeling and musical colour.

Music is the only field of study that requires regular and extended one-on-one interaction between student and teacher. The student-teacher relationship is a very special one, based on mutual trust and respect. Young students are often hungry for knowledge and experience: they turn to their teachers for support and advice, they share their insecurities and emotions. Music is all about expressing emotions, plumbing the depths of the soul or soaring in ecstasy, and a certain vulnerability and emotional intelligence is essential if the musician is going to communicate with honesty and passion. Good teachers know this – they encourage their students to know this too, enabling them to let go and free their spirit to play with feeling and musical colour.