Guest post by Dr James Holden

I’ve always really enjoyed playing the piano. However, I’ve always avoided doing my piano practice. This spring I decided to put an end to that. I was particularly motivated by the start of the annual 100 Day Project, in which people commit to doing something creative for 100 days. I determined that my project would be to teach myself how to play Chopin’s Nocturne op. 27 no. 2, a piece I’ve always loved but lacked the impetus and dedication to learn. To do this, I committed myself to practising for at least 30 minutes every day. What’s more, I decided to make myself publicly accountable by streaming my practice sessions on my Twitch channel.

In case you’re not aware, Twitch is a streaming platform usually used by gamers to broadcast themselves playing videogames. However, it’s also used by artists and other creatives to stream their ongoing work. At any one time you can usually find several pianists playing live in the ‘Music & Performing Arts’ category. These players are often watched by hundreds of viewers as they perform arrangements of popular songs and other tunes, improvisations and more.

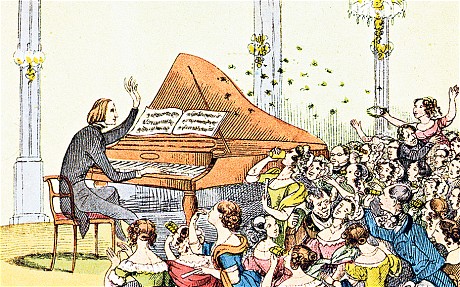

If these pianists are giving online concerts, they are less like modern concerts than they are nineteenth-century salon performances. Twitch allows real time interaction through a chat window which means that these pianist-streamers can engage with their audiences in real time between and even during pieces, and are therefore able to perform requests, respond to suggestions and otherwise chat with viewers.

My own Twitch streams are a little different. Firstly, my standard of playing is generally lower: I am an intermediate level amateur at best with limited repertoire (largely the result of my limited practice!). Secondly, I’m not attempting to give salon style performances. Instead, I’m ‘just’ broadcasting my daily piano practice.

Practice is normally private not public. It’s what precedes a performance; it’s not the performance itself. And yet, the simple act of streaming it on a public media platform means that my private practice does take on a performative aspect. Even if no one is watching – and that’s often the case on my channel – people could be watching. And that makes all the difference.

The performative aspect of my streams has necessarily altered my relationship to my practice. It has introduced an implied need to make it enjoyable to watch. This means, in the first place, choosing to work on a piece that will appeal quickly to viewers surfing between channels. The Chopin nocturne I’ve chosen is a beautiful work with relatively immediate appeal. However, it simply doesn’t have the mass recognition or popularity that a cover of a hit song would have. Secondly, the need to make my streams an enjoyable watch potentially risks altering how I practice. It feels as though I should play the work through coherently ‘in flow’ rather than working in a more deliberate, detailed fashion. It’s just not that much fun to watch someone play one bar over and over, or play a phrase slowed down to the point of unrecognizability. And yet, that is the kind of effort that is often required when practising.

On the plus side, Twitch’s interactivity means that it’s possible to get immediate positive reinforcement during practice. I was genuinely thrilled when a viewer typed in chat that my playing sounded good. The comment led me to think about the broader possibilities of learning on stream. I can imagine a practice session becoming something like an informal masterclass with knowledgeable viewers offering encouragement and advice.

Given my chosen piece, I can’t help thinking about all these issues in relation to the Romantic virtuosos. Chopin himself, of course, was a brilliant performer but famously averse to giving large concerts. Perhaps he would have enjoyed playing in the privacy of his own home to an invisible public audience on Twitch. I’m not sure how he would have felt about making the private work of practice public though. I certainly know how the older Liszt would have felt. It’s probably true that during his years as a touring virtuoso the younger Liszt did much of his practice in public on the concert platform itself. However, in later life as the stern master of Weimar he was famously dismissive of pupils who displayed poor technique during his masterclasses, berating them with the declaration: “Wash your dirty linen at home!” I am literally counting ledger lines during my streams so am certainly, musically speaking, washing my dirty linen in public.

I’m only a short way into #the100dayproject. Despite the complications it has introduced, the decision to stream has already had several positive effects. Firstly, it has given me the necessary commitment to keep practising. My advertised stream schedule makes me publicly accountable for my practice in a way I’ve never been before, not even when I had lessons as a kid. I have, as a result, stuck to the task far more than I would have done otherwise, and my playing has genuinely improved as a result. I’ve certainly made solid progress with the nocturne. Whilst it’s true that I’m still stumbling over the more challenging passages and continue to play wrong notes, I at least play them better than I did before. It turns out that regular practice really does make a difference!

A second consequence of my decision to stream my practice is that I now have a video archive of my progress. I can compare the video of my day 1 stream with, say, that of my day 21 stream and quickly see the progress. This is a source of positive reinforcement that offers continued motivation when things seem challenging. More immediately, the fact that Twitch makes streams available as VODs means that I can watch myself back straight after I finish my practice. I can listen to my playing divorced from the act of playing itself, which means I can hear things much more clearly. The critical reflection for which this allows feeds back into my following practice sessions.

Thirdly, I have become somewhat used to the idea of others watching me play (if not perform exactly) – which was a rare occurrence before. In particular, I’m more accustomed now to the idea of people seeing me struggle with a piece and play wrong notes. I’ve had to get over any embarrassment about my lack of technical ability or competence, and my playing is probably becoming freer as a result. I think, overall, that streaming is making me more forgiving of my mistakes.

I’m excited about where my 100 Day Project is heading. I’m certainly looking forward to hearing the improvements I’m sure to make in the days and weeks ahead, and to exploring new pieces alongside my current choice of nocturne.

I’ll be streaming my practice on my Twitch channel at 6pm UK time for about 30 minutes every evening until I reach day 100. It’d be great if you could tune in, say hi in the chat and give me some encouragement. Please do give the channel a follow whilst you’re there too. Can’t make it at 6pm? Don’t worry, you can always find videos of all of my previous practice sessions, so do stop by.

James Holden is an independent writer and academic. He is a Lisztian, a Proustian and a Nerd. He is currently streaming his piano practice every day at 6pm on his Twitch channel. Find out more about his work and publications on his website. You can also follow his progress on Twitter and Instagram.