To coincide with the release of her new album ‘Chopin: Voyage’, Russian pianist Yulianna Avdeeva talks about her life in music, balancing one’s artistic needs with the external pressures of a professional career, and how inspiration “can be found anywhere”.….

Who or what inspired you to pursue a career in music and who or what have been the most important influences on your musical life and career?

In my childhood I was surrounded by music. Although my parents are not professional musicians, they were great music lovers and had an upright piano at home, as well as a solid LP collection. At some point they realized that I was trying to play a melody that I had just heard with one finger on the piano, and took me to the Gnessin Special Music School. When I was 5 years old I entered the piano class of Elena Ivanova, with whom I studied for 13 years, until my graduation, and who became a family member for me. Thanks to her amazing admiration and approach to music, I was able to discover this magical world for me as well. However, the moment I remember so well, which was crucial to me, was my first public performance, when I was 6. I was supposed to play 2 Tchaikowsky pieces from his Children‘s album, and my parents and teacher were explaining that I shouldn‘t be scared by the light and people and the audience and should be concentrating on the music I’d play for them. I was not scared at all; on the contrary, I enjoyed very much communicating with the audience through the language of music! And I wished to perform again. So the solution for how to stay motivated for practice was found! I keep that feeling until today and am so grateful to be able to speak this universal language with people all over the world.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

I think the greatest challenge is to find out what your mental and physical needs are in order to achieve the most satisfying artistic result. This result depends on many factors, which I had to recognize and acknowledge in my preparation work as well as in my stage performance. Time management is one of the most essential elements; it means that I must know how I should organize my practice, so that I give each piece I perform enough space not only in my daily practice but also in my soul, since I need to “live” with a piece for a while so that it becomes, in a way, my co-creation. On the other hand, I have to know my limits — for instance, if I have a very tight schedule, how many programmes can I really handle? And does it make sense, artistically? My personal goal is to be in the best shape when I walk onstage, and it is probably a never-ending process to understand myself.

Which performances/recordings are you most proud of?

It is always very difficult for me to listen to my own recordings or the recordings of my own concerts. I almost always think, “Oh, now I would play that completely differently!”. This is the charm and challenge of music — it exists only in the moment when it is being performed, and it is not easy to capture this moment on any recording. So I very rarely listen to my own performances — with some exceptions, of course. For example, it is an amazing inspiration and joy to work with Bernhard Guettler, the sound producer I have worked with for my latest two recordings — Resilience, and Voyage, my new Chopin album, on the Pentatone label, featuring his late works, which has just been released. This particular recording experience was absolutely unique for me for two essential reasons: the location and the instrument. I was so lucky to make this recording at the one and only Tippet Rise Arts Center, in Fishtail, Montana, surrounded by nature and a wonderful team. And on top of that, I played the music on Vladimir Horowitz’s personal piano, which has an exceptionally long and warm sound that opens up like a flower.

When I first touched this piano in September 2022 at the TIppet Rise Arts Center, my first thought was, “This piano is my dream partner for Chopin’s music!”. So I am very thankful to Peter and Cathy Halstead and the entire team at Tippet Rise Arts Center for their most kind support; Mike Toya for his amazing care of the piano; Bernhard Guettler for his patience and his unlimited desire to explore the sound worlds; and the Pentatone team for bringing this recording to life.

Which particular works/composers do you think you perform best?

The moment I decide to play any piece, it becomes “the best and dearest piece” for me, otherwise I will not be able to find an authentic approach to it. Nevertheless, of course there are composers I admire so much, since they have an enormous emotional impact on me, such as Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Mahler, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and Bartok, to name just a few. A great discovery for me was Bernstein’s Second Symphony, “Age of anxiety,” in which the piano has a very important solo-like part. It was an exciting process to prepare this unique work, based on Auden’s poem, and I am so lucky to have performed it a couple of times in Spain and Italy and finally to play it in the United States with the Minnesota Orchestra and Robert Trevino on October 18th and 19th, 2024!

How do you make your repertoire choices from season to season?

The piano repertoire is just limitless, which is the pianist’s curse and blessing! My personal list of pieces I would love to play is getting longer every year, so I have to make decisions about what I would like to play next. Sometimes it takes a long while to decide on a recital programme; for me it is important that there is a certain concept, or at least a connecting idea between the pieces. The programme I am performing at Carnegie Hall on October 22, 2024 is a Chopin and Liszt recital. They were the two giants of the Romantic era, both unique performers, and both were trying out the most extreme ways of expression on the piano, even if they were moving on very different paths.

Next year I will be performing Shostakovich’s 24 Preludes and Fugues, op 87, which for me is one the greatest cycles for piano of all time. It was inspired by Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, which I will be playing in 2027. These cycles require my entire concentration in the preparation. At the same time, for next year I also prepared a programme that connects two composers you wouldn’t expect to see together — Chopin and Shostakovich. But Shostakovich was a participant at the first Chopin Competition, in 1927, in Warsaw, and he played Chopin a lot in his younger years. So it is always kind of a work of investigation to create a recital programme.

Do you have a favourite concert venue to perform in and why?

There are many; I could not pick only one. Some of the halls are very inspiring because of their history and the musicians who have performed there — like Carnegie Hall, or the Musikverein in Vienna, but also some modern halls are amazing because of their acoustics and atmosphere — for example, Disney Hall in Los Angeles, or Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg.

What do you do off stage that provides inspiration on stage?

I am convinced that inspiration can be found anywhere — it can be a color from the sky or of the leaves on a tree; it can be a conversation, or a great book, or even a smell — like the smell of the air in the autumn, or the aroma of a fantastic meal. I just have to be very open to be able to absorb it.

What is your most memorable concert experience?

It is difficult to say. In every concert I share a part of my soul, and my soul in turn keeps the memories of each single concert. And, as I mentioned, the music exists only in a moment when it is being performed and cannot be repeated — that is why each concert experience, even with the same repertoire, is always different.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

Artistic success for me is probably when I am able to present an interpretation of a piece which on the one hand comes as close as possible to the composer’s will — though this criteria is very subjective — so, on the other hand, it is about my personal feelings about the music, which should be very strong and authentic. And the message of the music I perform should be acceptable for the audience, otherwise I have failed to translate the music score into human feelings.

What do you feel needs to be done to grow classical music’s audiences?

It is essential to give access to music to the youngest. That can be through playing an instrument, singing, dancing, or any other kind of musical activity, because music also helps children to feel and articulate the emotions they experience. This is what makes human beings unique and irreplaceable. Later on, children who have been exposed to these experiences will decide whether they want to play or sing for their family, or go to concerts, or become a professional musician. Maybe they will not have any interest in it at all. But our goal should be to give them a chance to explore this magical world of music.

What advice would you give to young or aspiring musicians?

I would like to encourage young musicians to think, before they go on stage, about how lucky we are to be able to speak the language of music and share our passion with the audience. And it does not matter if their audience is big or small, or if it is a concert, an exam, or a competition — it is only music, which matters for the performer, and we should only focus on it. I am wishing you a long, happy life, full of wonderful sounds!

Yulianna Avdeeva performs music by Chopin and Liszt at Carnegie Hall, New York, on 22nd October. Find out more here

Yulianna Avdeeva’s new recording ‘Chopin: Voyage’ is available now on the Pentatone label.

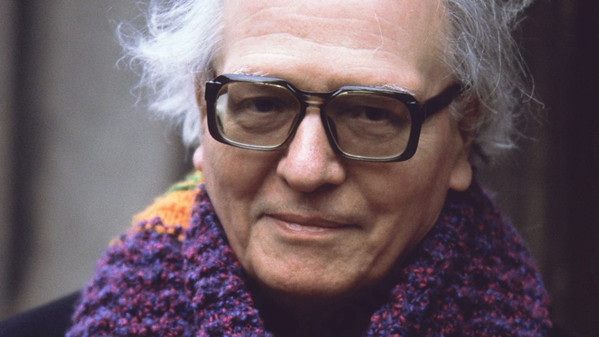

Olivier Messiaen is widely regarded as one of the most important composers of the 20th century, known for his unique approach to harmony, rhythm, and melody. His music is challenging for any performer, requiring not only technical skill, but also a deep understanding of his unique musical language.

The pianists presented here demonstrate a remarkable ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s music, bringing out its intricate harmonies, colours, textures and rhythms, as well as its emotional depth.

Yvonne Loriod

Messiaen’s student, muse and second wife, Yvonne Loriod was a highly accomplished pianist in her own right. Many of his piano works were written with her in mind. The Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus (“Twenty Contemplations on the Infant Jesus”) were dedicated to Loriod, and she premiered the work at the Salle Gaveau in Paris in March 1945. Loriod’s playing is known for its clarity and precision, as well as her ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s unique style. She recorded several albums of Messiaen’s piano music, including the complete set of Preludes and the Catalogue d’Oiseaux.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard

French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard is widely recognized as one of the foremost interpreters of Messiaen’s music. Aimard’s connection to Messiaen’s work runs deep, as he was a student of the composer and worked closely with him and his wife Yvonne Loriod. Aimard’s recordings of Messiaen’s piano music are considered some of the most authoritative, and he has performed Messiaen’s works all over the world to critical acclaim.

Angela Hewitt

Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt is perhaps best known for her interpretations of Baroque and Classical music, but she has also made a name for herself in more contemporary repertoire, including Messiaen’s piano music. Her recordings of Messiaen’s music are admired for their technical precision and attention to detail, as well as her ability to bring out the emotional depth of the music.

Steven Osborne

Scottish pianist Steven Osborne has performed Messiaen’s music all over the world, including the Vingt regards and Turangâlila Symphonie. Osborne expertly navigates the intricate harmonies and rhythms in Messiaen’s music with ease, bringing out the complex textures and polyrhythms that are hallmarks of the composer’s style. At the same time, he captures the emotional breadth and spiritual intensity that are crucial features of Messiaen’s music. His performances of the Vingt regards in particular are extraordinarily absorbing, meditative and moving, combining musicality, virtuosity and commitment. (I’ve heard Osborne perform this monumental work twice in London and on both occasions it has been utterly mesmerising and profoundly emotional.)

Tal Walker

For his debut disc, the young Israeli-Belgian pianist Tal Walker included Messiaen’s Eight Preludes. Composed in the 1920s, they are clearly influenced by Debussy with their unresolved or ambiguous, veiled harmonies and parallel chords which are used for pianistic colour and timbre rather than definite harmonic progression. But the Preludes are also mystical rather than purely impressionistic, and look forward to Messiaen’s profoundly spiritual later piano works, Visions de l’Amen (for 2 pianos) and the Vingt regards. Tal Walker displays a rare sensitivity towards this music and his performance is tasteful, restrained yet full of colour, lyricism and musical intelligence.

Other Messiaen pianists to explore: Tamara Stefanovic, Peter Hill, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Ralph van Raat, Benjamin Frith, Peter Donohoe

This article first appeared on InterludeHK

Olivier Messiaen is widely regarded as one of the most important composers of the 20th century, known for his unique approach to harmony, rhythm, and melody. His music is challenging for any performer, requiring not only technical skill, but also a deep understanding of his unique musical language.

The pianists presented here demonstrate a remarkable ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s music, bringing out its intricate harmonies, colours, textures and rhythms, as well as its emotional depth.

Yvonne Loriod

Messiaen’s student, muse and second wife, Yvonne Loriod was a highly accomplished pianist in her own right. Many of his piano works were written with her in mind. The Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus (“Twenty Contemplations on the Infant Jesus”) were dedicated to Loriod, and she premiered the work at the Salle Gaveau in Paris in March 1945. Loriod’s playing is known for its clarity and precision, as well as her ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s unique style. She recorded several albums of Messiaen’s piano music, including the complete set of Preludes and the Catalogue d’Oiseaux.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard

French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard is widely recognized as one of the foremost interpreters of Messiaen’s music. Aimard’s connection to Messiaen’s work runs deep, as he was a student of the composer and worked closely with him and his wife Yvonne Loriod. Aimard’s recordings of Messiaen’s piano music are considered some of the most authoritative, and he has performed Messiaen’s works all over the world to critical acclaim.

Angela Hewitt

Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt is perhaps best known for her interpretations of Baroque and Classical music, but she has also made a name for herself in more contemporary repertoire, including Messiaen’s piano music. Her recordings of Messiaen’s music are admired for their technical precision and attention to detail, as well as her ability to bring out the emotional depth of the music.

Steven Osborne

Scottish pianist Steven Osborne has performed Messiaen’s music all over the world, including the Vingt regards and Turangâlila Symphonie. Osborne expertly navigates the intricate harmonies and rhythms in Messiaen’s music with ease, bringing out the complex textures and polyrhythms that are hallmarks of the composer’s style. At the same time, he captures the emotional breadth and spiritual intensity that are crucial features of Messiaen’s music. His performances of the Vingt regards in particular are extraordinarily absorbing, meditative and moving, combining musicality, virtuosity and commitment. (I’ve heard Osborne perform this monumental work twice in London and on both occasions it has been utterly mesmerising and profoundly emotional.)

Tal Walker

For his debut disc, the young Israeli-Belgian pianist Tal Walker included Messiaen’s Eight Preludes. Composed in the 1920s, they are clearly influenced by Debussy with their unresolved or ambiguous, veiled harmonies and parallel chords which are used for pianistic colour and timbre rather than definite harmonic progression. But the Preludes are also mystical rather than purely impressionistic, and look forward to Messiaen’s profoundly spiritual later piano works, Visions de l’Amen (for 2 pianos) and the Vingt regards. Tal Walker displays a rare sensitivity towards this music and his performance is tasteful, restrained yet full of colour, lyricism and musical intelligence.

Other Messiaen pianists to explore: Tamara Stefanovic, Peter Hill, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Ralph van Raat, Benjamin Frith, Peter Donohoe

This article first appeared on InterludeHK