People assume that if you can read music, you can be a page turner for another pianist.

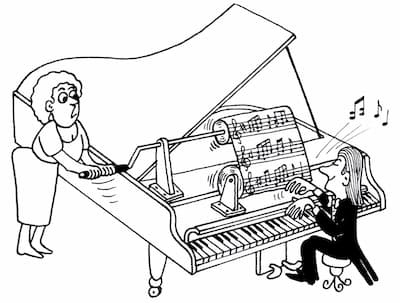

“You read music! You play the piano! You must be able to turn pages!” is the cry I frequently hear, and while all these statements are true, many people do not realise that page turning is an art in itself, a specialist skill which can help a performance go brilliantly, or turn a concert into a Feydeau farce.

These days at piano concerts it is still quite unusual to see a page-turner in attendance. The ongoing – and to my mind rather ridiculous – trend/burden of having to perform from memory (a habit which developed during the second half of the nineteenth-century, thanks in no small part to Franz Liszt and Clara Schumann) means that the turner is a fairly rare sight. It is more common if the pianist is playing as part of a chamber ensemble, though many pianists these days play from an iPad or similar device.

Page turning can be a nerve-wracking experience as the turner feels a great responsibility to “get it right” for the performer. Turns should be discreet and silent (turn from the left of the pianist, using the left hand to turn the top of the page). In effect the turner should be “invisible” – and the turner should be sure never to turn too early or too late.

In addition, the turner has to be able to understand and act correctly upon repeats, da capo and dal segno markings, and other quirks of the score. Turners also need to be alert to concert hall conditions: drafty halls can be stressful as stray gusts and breezes may blow the pages around. Page turners have to observe correct on-stage etiquette: they must follow the performer on to the stage and know not to rise from their chair nor fidget during pianissimo passages. They leave the stage after the performer has taken his or her applause and only step forward to receive plaudits if invited to by the performer.

Much of the turner’s role is about being able to “read” the performer’s body language and be acute enough to act upon sometimes highly discreet signals. Turners should not discuss their anxiety with the performer, nor expect the performer to give them tips or advice about their own playing or musical careers.

In fact, being able to read music is not necessarily a prerequisite of being a competent page turner as someone who gets too involved in reading the music may miss a crucial turn.

A quick poll around Facebook and X (Twitter) revealed some page-turning horror stories (turning the wrong pages, a severely damaged score with pages held together with sellotape, pages out of order) but also anecdotes celebrating page turning and page turners. One turner confessed that pianist Francesco Pietmontesi’s performance of the Liszt transcription of Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral’ Symphony had moved her to tears, and many people describe the privilege and pleasure of being able to turn for top international artists.

Modern times call for modern page-turning techniques and gagdets: scores stored on an iPad or other tablet device can be turned using a bluetooth foot pedal such as the AirTurn. Music publishers go to some lengths to engrave and print music in such a way as to facilitate easy page turns, but when this is not possible, one either ends up with photocopied sheets taped to the score, uses an automatic turner, or opts to have a page-turner, which can look more poised and professional.

Whatever route you choose, make sure your page turns are tidy, quiet and discreet – oh, and always thank your page-turner after the performance!