I first discovered this wonderful set of variations through a concert pianist friend, who performed them in a salon concert some years ago. As a lifetime lover of Schubert’s music, I was struck by how “Schubertian” this music is, especially in the minor key variations, where Haydn finds great emotional depth and expression.

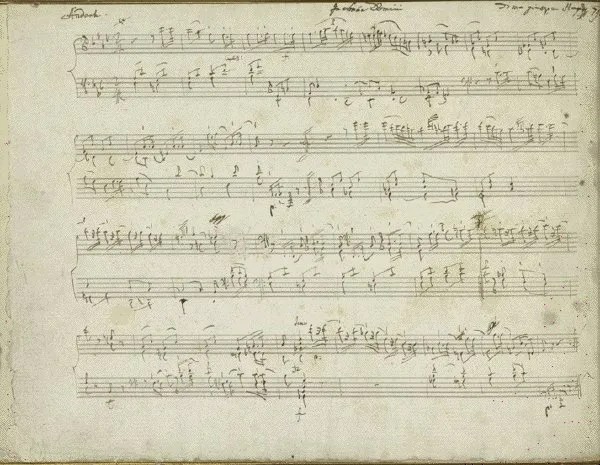

The piece was composed in 1793, and was described as a Sonata ‘Un piccolo divertimento’ in the autograph manuscript, written for a “Signora de Ployer” (probably the pianist Barbara Ployer, for whom Mozart composed the piano concertos K449 and K453). It was written at a time when the pianoforte was developing fast – Haydn would have encountered the new Broadwood piano with its more sonorous bass on his visits to London – and this piece really capitalises on the range and sonority of these bigger, stronger instruments.

The piece is a set of double variations, with the first theme in melancholy f minor and the second in warm F major. Two variations of each theme and an extended coda follow. While the music may look forward to Schubert’s lyricism and expressivity in its minor key episodes, it is also replete with Haydn’s characteristic wit achieved through articulation, dramatic pauses and embellishments, while his mastery of structure, harmonic innovation, and thematic development is evident throughout.

Haydn achieves a very effective and dramatic operatic dialogue as the music seamlessly transitions between passages of stark intensity and moments of delicate lyricism. For instance, the first variation introduces a more agitated character, with rapid figurations and abrupt dynamic shifts that inject a sense of urgency into the music. In contrast, the following variation may offer a more introspective mood, with subdued dynamics and lyrical embellishments suggesting a more intimate realm of expression.

Despite the relatively constrained harmonic palette, Haydn manages to infuse each variation with harmonic surprises and innovations that keep the player and listener engaged. Whether through unexpected modulations, chromaticism, or clever reinterpretations of harmonic progressions, Haydn demonstrates his ability to push the boundaries of tonal expression within the classical style. The result is a captivating, multi-faceted musical journey.

For the pianist, the music demands a high level of technical proficiency, particularly in terms of finger dexterity and agility. The variations encompass a wide range of technical challenges including rapid passagework and intricate ornamentation which require great precision. Minimal use of the pedal will ensure these passages retain their clarity. The music also requires sensitive dynamic shading to create contrast – from the softest pianissimo to dramatic fortissimo. A keen sense of the overall architecture of the piece will enable the player to balance the main themes with the diversity of the individual variations. Overall, this piece is very satisfying to play and its richness and complexity offers plenty of scope for expression.

Here is Alfred Brendel

This site is free to access and ad-free, and takes many hours to research, write, and maintain. If you find joy and value in what I do, why not