by Michael Johnson

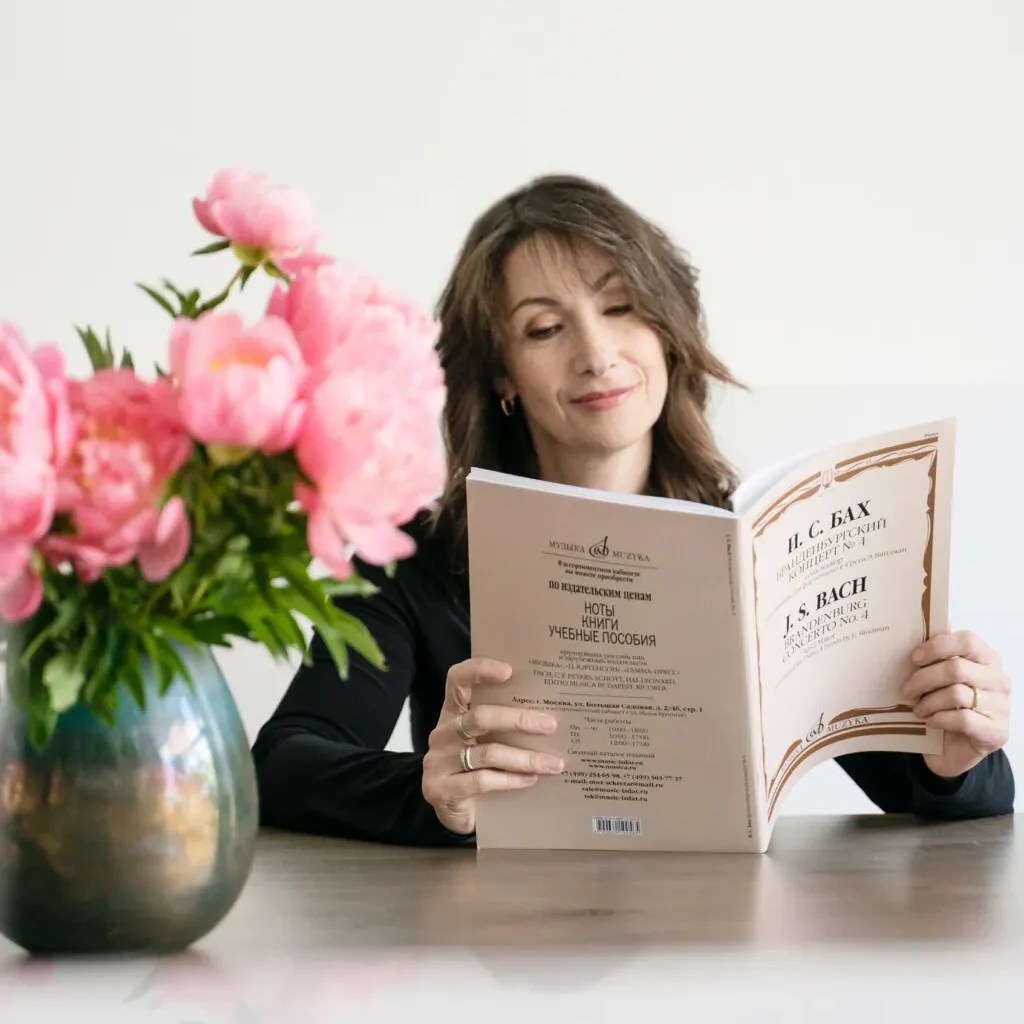

Latvian-American pianist Eleonor Bindman has often surprised pianophiles with her unique transcriptions, dating from Bach onward. The great cello suites, reworked for the modern piano, found new audiences in Europe, Asia and the United States. And her four-hand arrangements of all six Brandenburg concertos broke CD sales records.

She is achieving her ambitious aims – to widen the appeal of past keyboard and orchestral works, mainly the music of Bach, through her fresh and adventurous transcriptions.

And she is still doing it. Her new CD, which she cleverly titled AbsOlute, brings a flowing sense of joy to the Bach lute suites. They have never been heard like this.

“I don’t want to bore the listener,” she tells me in an extended interview. “I try to make my intentions clear about what I am doing.“

Traditionally, transcribers and arrangers have felt constrained by Bach’s already “perfect” compositions. But she is not about improving Bach, she says. “Not being a composer myself, I find that transcribing still gives me a feeling of creating something new.“

An imported New Yorker, Ms. Bindman speaks in an accent she brought with her from her native Riga, Latvia’s capital. Her American career has flourished as a performer, a transcriber and teacher. For several years she taught private students in her New York home, playing her beloved “mellow” Bosendorfer, perfectly chosen to enrich her lute scores. In recent years she has taught less frequently, being overwhelmed with massive transcription projects such as the four-hand piano version of the Brandenburgs and the larger Bach orchestral suites.

Is she Russian-trained? Not quite. She never studied in Moscow but her first teacher came from the great Heinrich Neuhaus line. Her professor Theodore Gutman was a Neuhaus student and her second teacher was Lev Natocherny, a product of the Moscow Conservatory, so the Russian tradition found its way into her sensibilities.

She cites the Russian pianist and conductor Vladimir Feltsman as a major influence. We have “similar temperaments” she says, so his teaching was easy to assimilate.

It is now time to focus on getting a fresh perspective, she says, a new look at Bach’s music. “In the past year or so, I’ve become a little less hesitant, a little less inhibited, even adding ornamentation that does not agree with any particular convention.”

Ms. Bindman has relied on lute recordings to help her find the piano voice she wanted. She cites the CDs of Italian Evangelina Maccardi as an influence and probably the best of the lutenists playing today.

Critical acclaim seems to have come easily to her. Some reviewers praise her transcriptions and Bach originals without holding back. One fell in love with her Partitas, calling her a “marvellous Bach performer”. “The prelude from Partita 1, he wrote “is deliciously slow and expressive, with unexpected marking of inner voices, beautiful ornamentation, shimmering tone.… There’s not a bad movement in the bunch.”

In this YouTube clip, Lute Suite in C minor, BWV997, her easy mastery of the transcription can he seen, heard and felt:

Ms. Bindman balances her note-perfect clarity with rubato touches that bring out the emotion that some Bach interpreters eschew. Her strong feelings emerged when I raised the subject of respecting the score to a fault. Bach should be very emotional, she insisted. “It’s not about playing the right notes at the right time. He wanted to leave room turn it into your Bach”.

Among her collection of videos posted on YouTube and on her own internet site are glimpses of her impish wit. In one version of the suites BVW 996-998 she dressed in 17th-century attire, including a voluminous wig and custom-made shoes. In this clip, note the swaying body language and confident, if silent, foot-tapping (both feet simultaneously). Her joy is uninhibited.

Edited excerpts from our Q&A interview:

You were obviously enjoying this. Smiling and rocking on the bench, you are conveying the joy Bach intended. Is there an actor in you trying to get out?

No, I don’t think so, but I’m glad I wasn’t the only one who had fun.

You cannot sit still while playing Bach. You almost dance to his music, don’t you? How do you reconcile your changes with the “perfect” scores you started with?

Well, not being a composer, I find that transcribing still gives me a feeling of creating something new. Some musicians feel constrained from doing very much with it. Not I!

Aren’t you also a jazz fan?

Yes, I also love jazz and the freedom it gives you, and I always try to bring a fresh, improvisatory element to my playing.

Bach predated the modern piano by more than 200 years so how does one try to recreate what his compositions would have sounded like in his day?

His lute suites were originally composed for the lautenwerk or lautenwerck (lute-harpsichord), one of Bach’s favourite instruments, similar to the harpsichord.

The 17th-century lute came to his attention through his son CPE Bach who was personally acquainted with a prominent lutenist of the day. Inevitably the lute became part of the Bach family.

You have remained independent-minded in your development as a musician but perhaps you could name principal teachers who have guided you?

Of course there were various teachers along the way, with pianist and conductor Vladimir Feltsman being the most important one.

You mix the Bach clarity with your own emotions, to make us love the music you are playing. How do you dare?

I am concerned about the listening experience. I don’t want to bore the public. I try to make my intentions clear about what I am doing. Bach can and should be very emotional. Playing him is not about hitting the right notes at the right time. He leaves room turn it into your Bach. Now that I have done my cello suites and the lute suites I feel I have a lot more data. I studied the scores so I could decide what I could do with them.

Haven’t you helped bring some international attention to these delicate lute suites?

Yes, many pianists do not know this music until they try the transcriptions.

Your reputation rests on your personal treatments of Bach. What other composers attract you?

Bach’s music is an endless source of wonder. But I also love Liszt, especially his poetic and mystical side, and have had some transformative experiences while playing his music. I feel a special affinity for the musical personalities of Schumann and Brahms, and the Russians, of course – Mussorgsky, Rachmaninov – since they permeated my upbringing. I absolutely revel in Spanish music, particularly Albeniz.

In an interview with The Cross-Eyed Pianist, you were asked what your definition of success is.

Being able to hold people’s attention and transport them into a different time and place.

AbsOlute is available on CD and streaming on the Orchid Classics label