Kapustin: Between the Lines

Ophelia Gordon, piano

Nikolai Kapustin (1937–2020) occupies a distinctive place in 20th- and 21st-century music. A classically trained pianist and composer, Kapustin cleverly fused the formal, structural rigour of classical music with the rhythmic vitality and improvisational idioms of jazz. His works defy easy categorisation: though they sound spontaneously jazzy, they are entirely notated in classical form, leaving no space for actual improvisation. This paradox became the hallmark of his style.

Born in Horlivka, Ukraine, Kapustin studied piano at the Moscow Conservatory, under Alexander Goldenweiser, at a time when jazz was still viewed with suspicion by Soviet authorities. Kapustin’s fascination with American jazz pianists like Art Tatum, Oscar Peterson and Erroll Garner led him to explore the genre secretly and he absorbed its harmonic language, rhythmic energy, and phrasing to create his own compositional language. His music is vibrant, cerebral, witty, exuberant and alive.

British pianist Ophelia Gordon makes a striking recording debut with this album of works by Nikolai Kapustin, drawn to his music as it reflects her own background (she grew up in a household full of music, both jazz and classical), her musical versatility and her desire to challenge the barriers between different genres of music.

Ophelia says, “I dream of a world where classical and jazz musicians can perform side by side, with no gatekeeping or barriers. Kapustin’s music makes that dream feel possible. It sits beautifully in the space between genres. It speaks directly to jazz musicians through its harmony and rhythm, and to classical musicians through its texture and form.”

This album is a celebration of the space “between the lines” where Kapustin’s music sits. In preparation for the recording, Ophelia tracked down many long out-of-print vinyl recordings of the composer’s own performances to find the essence of Kapustin’s voice. The recording is also a milestone in that it’s the first full release of Kapustin’s music by a female British pianist.

The album opens with Big Band Sounds, Op. 46 (1986), a piece rich in swing and the textures and timbres of Big Band jazz. Ophelia sashays through it with panache, making a bold opening statement for the rest of her debut album.

Selections from the 24 Preludes follow. Based on Chopin’s model, most of the Preludes presented here are upbeat and foot-tapping, but No. 5 in D Major is more wistful, with hints of Bill Evans. Contemplation follows, a gentle, introspective piece which conjures up a late-night smoky jazz club. Ophelia gives this a wonderful spaciousness, so much so that it sounds improvised there and then.

The Paraphrase on “Aquarela do Brasil” is Kapustin’s take the famous Brazilian standard “Brazil,” composed by Ary Barroso in 1939. Ophelia played along with a samba beat “to lock into the groove” and the piece has a joyful, pacey mood, rich in colour and textures, with occasional moments of almost Lisztian bravura.

The eight Concert Etudes are probably Kapustin’s most well-known pieces and each has a distinct character – punchy, impressionistic, groovy, funky, the Etudes reflect the influences of jazz greats such as Erroll Garner, Art Tatum, Bill Evans, Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock. Ophelia really revels in this music, switching effortlessly between the different characters of each Etude – from the shimmering sixths (perhaps drawn from Chopin?) to the driving energy of Toccatina. There are sonorous bass sounds and hints of Rachmaninov in some of the chords, reminding us of Kapustin’s heritage. Performed here as the complete set, the Etudes are witty, poetic, fierce, relentless, and often beautiful too.

To close, the Paraphrase on Dizzy Gillespie’s “Manteca” for Two Pianos. With its nod to the virtuosic paraphrases of Franz Liszt, with its dramatic flourishes and sparkling fioriture, the piece has a wonderful vibrant energy. Unable to find another pianist with whom to record the piece, Ophelia learnt both parts herself:

“The process was lengthy and difficult but incredibly rewarding. I split the parts into “rhythm” and “melody.” Though both switch roles, it was essential to record the rhythm part first, then play the solo part alongside it. I now perform this live with the rhythm coming through a PA system!”

Recorded on a characterful 1961 Steinway, the piano sound is rich and warm, colourful and immediate, and engineered with a microphone setup designed to balance the immediacy of a jazz trio with the depth and clarity of the classical solo piano. Ophelia plays with a natural virtuosity which never feels contrived nor forced, completely at home with Kapustin’s rhythmic vitality, and myriad harmonies and textures. She clearly loves this music because, as she herself says in the notes, it allows her to “be all of myself at the piano”.

With detailed notes by Ophelia Gordon herself, lending a more personal take on traditional liner notes, this is an impressive debut recording that leaves one wanting to hear more from this bold and authentic artist.

Kapustin: Between the Lines is released on 14 November on the Divine Art label (CD and streaming).

(Artist image: Ben Cillard)

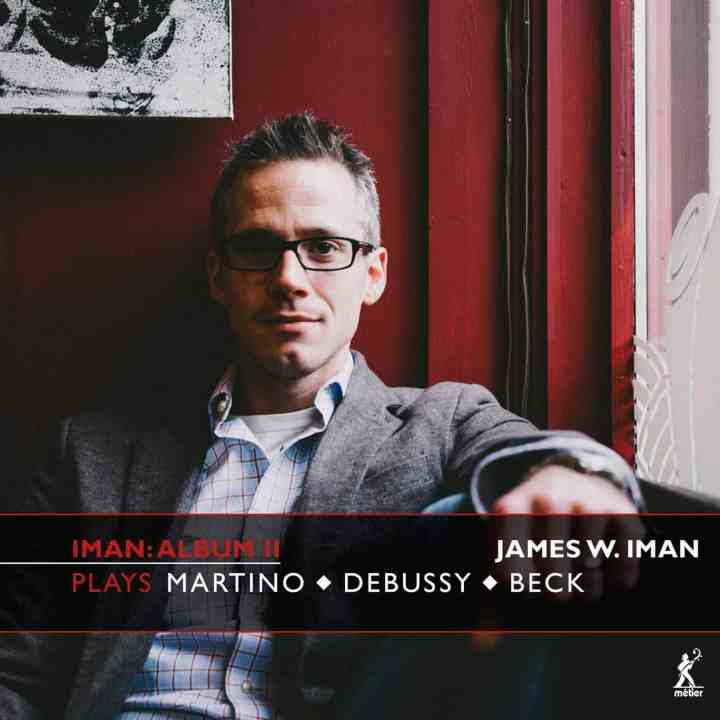

In his latest album, American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s everygreen Images alongside works by Jenny Beck and Donald Martino

In his latest album, American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s everygreen Images alongside works by Jenny Beck and Donald Martino