In his latest album, American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s everygreen Images alongside works by Jenny Beck and Donald Martino

In his latest album, American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s everygreen Images alongside works by Jenny Beck and Donald Martino

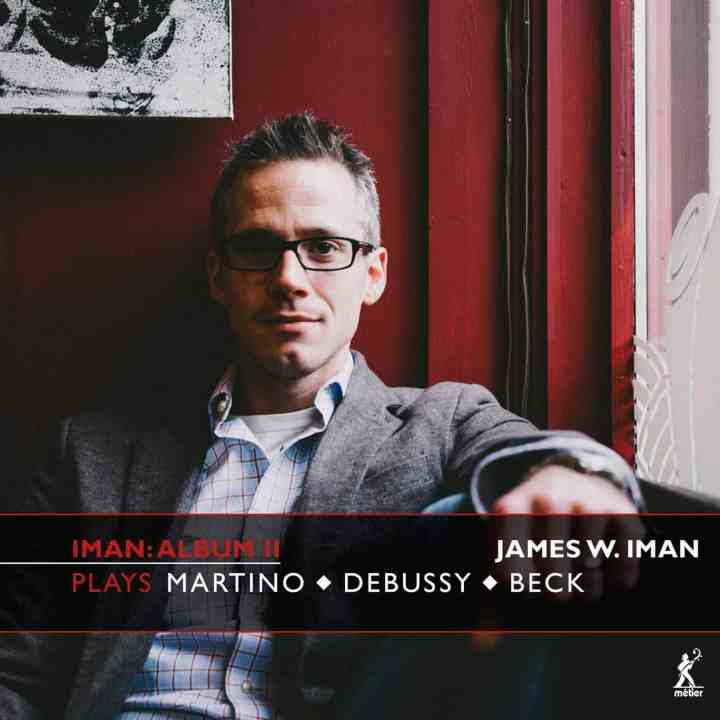

IMAN: ALBUM II James W. Iman, piano (Divine Art Recordings)

This second album from American pianist James Iman places Debussy’s ‘Images’ alongside works by Donald Martino (1931-2005) and contemporary composer Jenny Beck (b.1985), whose work ‘Stand Still Here’ receives its premiere recording on this disc.

A specialist in music written since 1900 – with an emphasis on music written since 1945 – James Iman’s repertoire spans many stylistic developments since Debussy. He is particular in his study and research of the music he performs and records to enable him to find fresh interpretations and approaches to the familiar, as well as presenting the new and more leftfield corners of the repertoire to listeners. When I reviewed his debut album, I was impressed by his willingness to rise to the challenge of this music and meet it head on with conviction and musicality, alert to its myriad details and quirks. He is perhaps most at home in the contemporary and more unusual, yet on this second album, he displays a remarkable appreciation of Debussy’s music which I really enjoyed, allowing me to hear these well-known pieces afresh.

James Iman has, by his own admission, taken a very different approach to Debussy, one which some may find controversial. I asked James to explain how he arrived at his interpretation of the works by Debussy on this disc:

“There are a few factors that went into my conception of these pieces. The first was a general frustration with recordings, and the homogeneity of most performances. This, of course, isn’t a new phenomenon, nor one specific to Debussy but, for whatever reason, it bothers me more in his music. While first digging into these pieces, my approach was probably similar to most pianists; you digest the text, and find the bits you think are interesting, and come up with an interpretation that highlights them. At first, my goal wasn’t to present a radical departure from typical interpretations, but the further into Debussy I dug, the more it seemed necessary. Improvisation was almost a character trait of Debussy. He would improvise at the piano before class, and for hours at parties. Moreover, Debussy’s performances of his own pieces were said to sound improvised. Likewise, one of the things that Debussy expressed, repeatedly, was his desire to compose music that sounded as though it was being improvised. This was, of course, mainly an aesthetic concern – Debussy was looking to overcome the strictures of convention, and was (primarily, perhaps) referring to the perceived structure of his works and not necessarily the nature of the performance.

Two things crystalized all of these ideas for me. First was my discovery of the recordings by Paul Crossley. I don’t know how well-known his performances are, but they were new to me, and a revelation. Absolutely every measure is inflected! Every single note feels important. Somehow, miraculously, he avoids making the music sound manic. Second was discovering Debussy’s own recordings of his works. It’s really difficult to describe just how radical Debussy’s playing is! Notes of the same duration are two distinct speeds within the same phrase and occasionally within the same bar. He pushes and pulls tempo without warning and to degrees that would be regarded as well-outside what we might consider “good taste.”

All of these things together made it clear to me that, not only could I approach these pieces differently, but that I should. We’re a history-obsessed culture – we’re excessively concerned with the fidelity of a text (the “letter”), whether it’s law or religion or music. I wanted to concern myself more with the spirit of the text – get the notes, of course, but try to capture what Debussy has clearly shown was his intention.”

Iman’s ‘Images’ are bold and direct, brightly-lit and vividly hued: no impressionistic veils of sound here nor excessive use of the pedal. Mouvement thrums and pulsates; Hommage à Rameau has a stately grandeur that feels at once ancient and modern; the darting fish of Poissons d’or are not shy goldfish but bold, muscular Koi carp. Debussy’s vibrant musical language comes to the fore in Iman’s playing with an emphasis on the more piquant or crunchy harmonies and timbres, rather than melody. Attention to these details perhaps comes from Iman’s experience with more contemporary repertoire: there are passages where Debussy sounds ultra-modern when Iman highlights interior or bass details which are sometimes lost or underplayed in other performances of this music. Given Debussy’s dislike of the term “impressionist” in relation to his music, I suspect he may have enjoyed Iman’s interpretation.

After the myriad colours, harmonies and rhythms of Debussy, Jenny Beck’s ‘Stand Still Here’ – a suite of five terse miniatures each no longer than four minutes at most – provides an extraordinary contrast. These introspective, intimate pieces have a remarkable emotional presence, yet expressed so sparely, almost minimalistic. Yet, like Debussy, Beck exploits the timbres and sonorities of the piano to create a hypnotic intensity. Of this work, Iman says, “I have played Stand Still Here more times than any other work in my repertoire”. Through a deep familiarity, and affection, for this work, Iman is able to achieve a wonderful sense of spontaneity and improvisation: notes linger, vibrate, shimmer and fade. It’s a deeply absorbing interlude on this fascinating disc.

The final works are by Donald Martino. He studied with Roger Sessions and Milton Babbitt, two of America’s foremost twelve-tone composers, but did not adopt the practice himself until he studied in Italy with Luigi Dallapiccola (though he never described himself as a “twelve-tone composer”). From Dallapiccola, Martino took a more lyrical approach to composing twelve-tone music, which culminates in his Fantasies and Impromptus. Like Debussy and Jenny Beck, Donald Martino enjoyed the myriad sonorities the piano offers. Iman gives a masterful performance of this collection of pieces which combine virtuosity and expression, improvisation and structure, making them the perfect complement to Debussy.

IMAN II is available on the Divine Art label and via streaming platforms

This review first appeared on my sister site ArtMuseLondon.com