Who or what inspired you to take up the piano and pursue a career in music?

My mother sent my father to the American G.I. flea market to buy a western suit in order to attend a cousin’s wedding. My father came home without a suit; instead, he returned with an old turntable and a stack of LP records. In the stack of LPs were all of the most important works from Mozart’s violin sonatas, to Tchaikovsky’s sixth symphony, Beethoven’s piano concerti and symphonies, as well as Rimsky Korsakov’s Scheherazade. My father wanted all of his children to learn how to make music, so he forced me to take up the piano. He took me to live concerts where I found the experience took me to the most beautiful world that humans can experience. I remember those blissful hours in concert halls watching artists strive to achieve something that seemed so impossible from a child’s point of view, and that inspired me to want to be one of them. I am always trying to achieve something that is beautiful and inspiring.

Who or what have been the most important influences on your musical life and career?

I have to say it is my husband David Finckel, who is one of the most disciplined and imaginative musicians. To have a lifetime partner that is committed so deeply to an unwavering belief in the power of music, is so determined to uphold the highest standard, and is in constant quest for excellence in his musical life has influenced and affected me every single day. It is a blessing to have a lifetime partner who is in the same pursuit as a musician and artist.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

I am a very optimistic person. I love to be challenged, so I don’t really remember meeting any challenges, I only remember seeing opportunities.

Which performances/recordings are you most proud of?

My recordings are like my children, I cannot possibly tell you which one I like more than the others. And I rarely have a performance that I am completely satisfied with, but I am always proud of the concert as long as my audience seems happy.

Which particular works do you think you play best?

I love Schubert, Chopin, Dvorak and Beethoven. That doesn’t mean I play them best, but I know that I always try my best when I perform any works.

How do you make your repertoire choices from season to season?

I carry a large repertoire each season, between 40 to 60 pieces. My repertoire choice usually comes from the design of specific program. In the program, you need to find balance and variety. It is a combination of my passion that particular season and my program design where I find that magic formula that provides audiences with the most satisfying musical experience.

Do you have a favourite concert venue to perform in and why?

Alice Tully Hall in New York City, one of the greatest halls, with its warmth and beauty of sound, as well as its complete silence. Alice Tully Hall also has the greatest piano in the world. It is an oasis for any musician to make music in such a beautiful space with such perfect acoustics. The color of the wood is modeled after the most gorgeous Italian string instruments, and the intimacy between the audience and the performers provides all the inspiration one would need.

Who are your favourite musicians?

My favorite musicians are Vladimir Horowitz, Martha Argerich, Mstislav Rostropovich, Jascha Heifetz…

What is your most memorable concert experience?

I played three concerts the week after September 11, 2001 for the most attentive audience. In all of the slow movements I could hear the sobs of the audience, as well as my own. Those were the most important concerts that I ever played in my life.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

My definition of success is that I improve everyday, I try my best all of the time, and I make music that hopefully touches people’s hearts.

What do you consider to be the most important ideas and concepts to impart to aspiring musicians?

I tell young musicians to be truthful to the score, always work hard, and be ready to be a strong advocate on behalf of great music, the music you truly believe in.

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

My idea of perfect happiness is to play a great concert, have a great martini and a great meal afterwards, get a good night’s sleep, and wake up in time to catch my next flight.

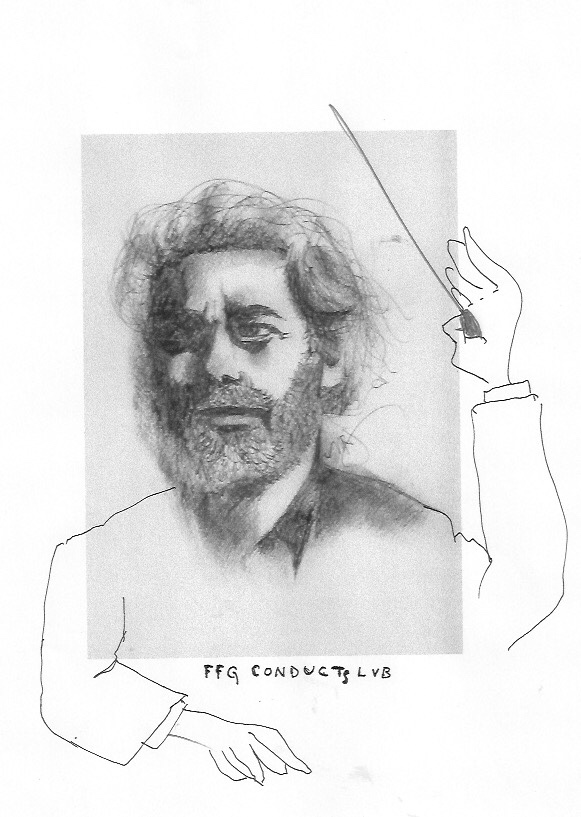

Wu Han LIVE III is the third collaborative release between the ArtistLed and Music@Menlo LIVE labels, featuring pianist Wu Han’s recordings of Fauré’s magnificent piano quartets from past Music@Menlo festivals.

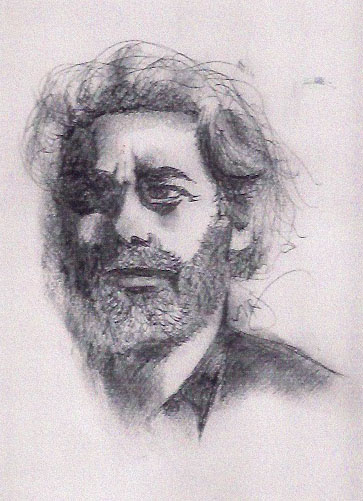

Wu Han is a Taiwanese-American pianist and influential figure in the classical music world. Leading an unusually multifaceted career, she has risen to international prominence through her wide-ranging activities as a concert performer, recording artist, educator, arts administrator, and cultural entrepreneur

(Artist photo: Liza-Marie Mazzucco)

Guest interview by Michael Johnson

Guest interview by Michael Johnson