guest post by Michael Johnson

It has been a long journey I enjoy re-living as I take note this year of the great Ludwig van Beethoven’s 250th birthday. As a practicing music critic and journalist from American corn country, I call myself a hick hack but I experience meltdown at almost everything the great man wrote. How can one not love Beethoven?

Well, at first he might seem an unlikely idol for me, growing up in a small town in the flat, agricultural Midwest, too far from everything. My ears rang with Tennessee Ernie Ford’s recording of “Cry of the Wild Goose”, a mindless vehicle for the late crooner, but I ate it up. My five brothers and sisters and I played it over and over on our new 45-rpm console. It was one of the records that came free with the player. There was also “Whoopie Ti-Yi-Yo” by the Sons of the Pioneers.

Only after I escaped from Indiana and moved to California for university education did I open myself to new worlds of music. I first discovered Baroque, an instantly accessible form that had me humming along and tapping both feet. Friends observed my head bobbing uncontrollably as Vivaldi, Scarlatti, Purcell, Corelli, Lully, Campra and others excited me.

Finally a colleague on the San Jose State University school newspaper took me aside and promised much better thrills – more satisfying than cannabis and completely legal. He had just come from a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth and was still marveling at the experience. “You gotta hear this,” he gushed. “It will knock your socks off.” He was almost right.

I never lost my socks but over the next year I built up a complete library of Beethoven symphonies on vinyl LPs, moving backward from Nine to One. The scope and variety left me spinning, and I have never stopped exploring the rich oeuvre of symphonic, choral, solo piano and chamber music Ludwig left us.

In my early piano studies at university I played what every schoolgirl plays – the Bagatelle “Für Elise”, moving on to his “Moonlight Sonata”. And by shameless cherry-picking, I plunged into parts of the “Diabelli Variations” and a few of his 32 piano sonatas, guided by tempo markings such as “Largo”, “Andante” and, my favorite, “Grave e maestoso”. The slower the better.

I gave up piano lessons when I grew tired of wandering around on the famous plateau students hit after the easy stuff is done. I have spent the rest of my life picking out passages of Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, and Liszt I catch on radio as I tell myself, “Hey, I could play that.” Sometimes I get the sheet music off the internet and start to work.

Now my CD collection is particularly rich in Beethoven. I am listening to the late string quartets as I write this, and his piano trios are among my favorites. Of course nothing beats the Ninth, or even the Fifth. I also relate to the emotional Seventh.

I gradually became a music writer and critic, keeping myself busy attending concerts and writing my reaction to the players’ efforts. The idea of a pianist alone on a spacious stage playing for an hour and a half from memory, no safety net, still strikes me as one of the great feats of human courage and accomplishment.

By chance, I have done interviews recently with two pianists who have performed the five Beethoven piano concertos from memory, conducted from the keyboard, in one day – François-Frédéric Guy and Rudolf Buchbinder. François also plays all the sonatas from memory over three weekends.

I liked Rudi’s dismissal of my praise for his “marathon” performances. “Ach,” he said, “it’s nothing special.” François said he is not running a marathon here, he is showing the audience how Beethoven’s creativity evolved.

Beethoven has a way of remaining ubiquitous. His work is eternal and musicians love performing it. New recordings appear like clockwork. In this crowded field, no one, in my opinion, has surpassed Wilhelm Kempf’s heart-stopping sonatas.

In many other ways Beethoven keeps entering my life. When I was based in Paris as an economic journalist I received news that my father was failing fast with lung cancer after a lifetime of smoking two packs a day of Lucky Strikes. We were never close, but I picked up the phone and asked my mother to put him on. Silence for a few minutes. She came back and said, “He is lying on the hardwood floor, the only place he can find comfort. He is listening to Beethoven’s Ninth.” He never made it to the phone. He died two days later.

Michael Johnson is a music critic with particular interest in piano. He worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Moscow, Paris and London over his writing career. He is the author of five books and divides his time between Boston and Bordeaux. He is a regular contributor to The Cross-Eyed Pianist.

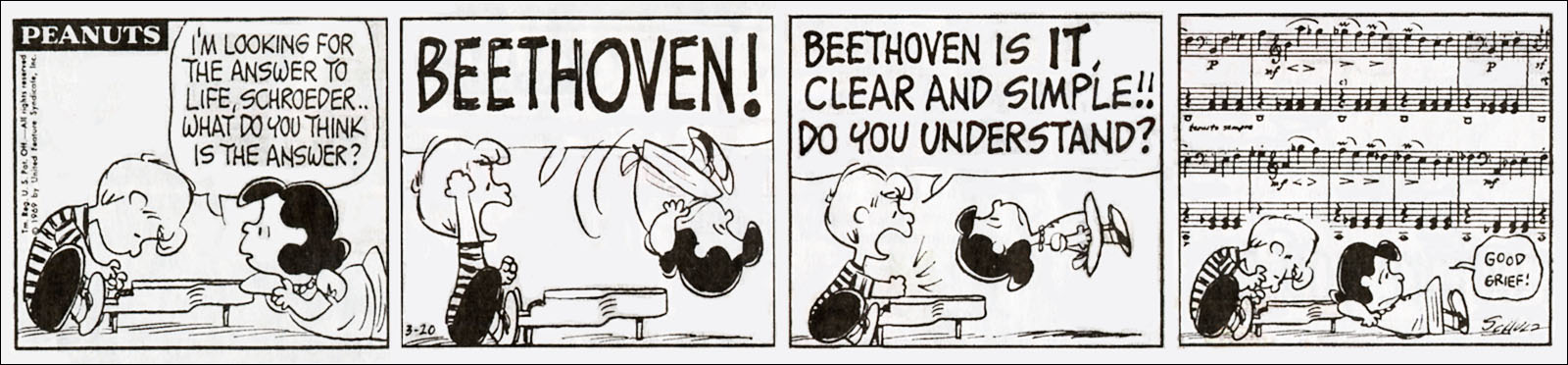

Illustration by Michael Johnson