Who or what inspired you to pursue a career in music and who or what have been the most important influences on your musical life and career?

Music was part of the house in which I grew up as both my parents were wonderful musicians: my father was the Cathedral organist in Ottawa, Canada for 50 years, and my mother a piano (and English) teacher. She started me off when I was three years old, though I was already playing some toy instruments before that. So they were the biggest influences of course. I always had excellent teachers: Earle Moss and Myrtle Guerrero at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto (I never lived in Toronto, only went there for lessons); and especially the French pianist Jean-Paul Sevilla at the University of Ottawa. He was a huge influence, being a marvellous player himself, especially of the Romantic and French repertoire. But he was also the first person I heard perform Bach’s Goldberg Variations, which he did magnificently. I also studied classical ballet for 20 years from the age of 3 to 23, and that was a huge influence on me in every way, and very beneficial for playing the piano. I also sang in my father’s choir, played violin for 10 years, and also the recorder. All of those things made me the musician I am today.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

The whole thing has been a challenge. From beginning to end. Even if you have the talent, it’s nothing without the work. I’ve sacrificed a lot to be where I am today, but that’s OK. I struggled to get known as a young pianist. I did many competitions. I won some, got thrown out in others. When I did win a big prize (the 1985 Toronto Bach Competition), at least that meant I didn’t have to do any more. But then it was up to me to keep the momentum going. I’ve had good and bad experiences with agents. I’ve always done a lot for my own career. An enormous amount, actually. It was a challenge to come to London in 1985 when I was totally unknown and make a name for myself here. I worked hard at that. It took me 15 years of renting Wigmore Hall myself before I started selling it out and being promoted by the hall instead. The recording contract with Hyperion I got myself. That was one of the best things ever, also thanks to the great integrity that label has. Artists of my generation have also had to adapt to the social media world and work with that in a good way. Perhaps the biggest challenge is to stay sane and healthy when you are doing a job that demands the utmost of you, both physically and emotionally.

Which performances/recordings are you most proud of?

I’ve been happy with every recording I’ve done for Hyperion in the past 26 years. I never leave the studio unless I feel we have the best possible versions. Of course things change over the years—that’s only natural. But each CD is a document of how I best played the works at that time. Apart from my Bach cycle, I am happy that I’ve recorded so much French music (Ravel, Chabrier, Fauré , Debussy, Messiaen, Rameau, Couperin) and also the more recent Scarlatti CDs. Great stuff! I’m almost finished my Beethoven Sonata cycle which has taken me 15 years, and that gives me enormous satisfaction.

Which particular works do you think you perform best?

I’ve always done a very wide repertoire. People think I only play Bach, but no. In my teenage years I was more known for the big romantic works like the Liszt Sonata and the Schumann Sonatas, though of course everybody knew that I played Bach. I think it’s important for a good musician to play in many different styles. On the whole I like to take complicated works and make them sound easy (like Bach’s Art of Fugue).

What do you do off stage that provides inspiration on stage?

Everything you experience in life goes into your music and your interpretations. Talking with friends, reading books, going to the theatre, travelling, seeing a movie, reading the news, experiencing the tragedy of this awful pandemic….all of that ends up in what you produce later on at the piano.

How do you make your repertoire choices from season to season?

Often it follows recording projects because I like to perform what I am going to record, of course. But also it depends on what people ask you to do. It’s a very difficult thing, choosing programmes for a whole year, and I’ve never been one to play the same programme all season. I can change several times a month.

Do you have a favourite concert venue to perform in and why?

Oh, just one where people don’t cough!

What do you feel needs to be done to grow classical music audiences/listeners?

Just go out and perform each time in a way that makes people want to hear you again. Then you build an audience. If a concert is boring, nobody is going to return. You have to make people really want to go to hear you. Of course there’s all the stuff about developing a younger audience, and that’s extremely important. I support a project in my home town of Ottawa, Canada called ORKIDSTRA which gives free music lessons to children in under-served areas of the city. It’s wonderful to see how much learning an instrument adds to their lives and to their general development and sense of community.

What is your most memorable concert experience?

I don’t know about most memorable, but certainly playing the Turangalila Symphony at the BBC Proms in the Royal Albert Hall in July 2018 was a night to remember. Fantastic performance, conducted by Sakari Oramo. Very moving. Great audience. That’s the right hall for that piece. If I never play it again it doesn’t matter—I had that experience.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

Success? Well, playing a piece you have worked very hard on, and finally memorising it and performing it well in public. That gives great satisfaction. Material success, as we have seen with this pandemic, can vanish in an instant. I suppose success is when concert promoters think of you when they are putting together their season. You have to have something they want to sell. When you have that something and have totally kept your integrity and got there because you’re good and worked hard, then I think that’s success. But I don’t really like to think of “success”. It’s very fragile.

What do you consider to be the most important ideas and concepts to impart to aspiring musicians?

To play their instrument with joy and not to be stiff and tense when they play. They must easily communicate with their audience and show that every part of their body is feeling the music.

Where would you like to be in 10 years’ time?

Alive.

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Playing for a friend and having a meal afterwards.

What is your most treasured possession?

My new Fazioli F278 concert grand piano.

One of the world’s leading pianists, Angela Hewitt appears in recital and as soloist with major orchestras throughout Europe, the Americas, Australia, and Asia. Her interpretations of the music of J.S. Bach have established her as one of the composer’s foremost interpreters of our time.

Born in 1958 into a musical family (the daughter of the Cathedral organist and choirmaster in Ottawa, Canada), Angela began her piano studies age three, performed in public at four and a year later won her first scholarship. In her formative years, she also studied classical ballet, violin, and recorder. From 1963-73 she studied at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music with Earle Moss and Myrtle Guerrero, after which she completed her Bachelor of Music in Performance at the University of Ottawa in the class of French pianist Jean-Paul Sévilla, graduating at the age of 18. She was a prizewinner in numerous piano competitions in Europe, Canada, and the USA, but it was her triumph in the 1985 Toronto International Bach Piano Competition, held in memory of Glenn Gould, that truly launched her international career.

Read more

Olivier Messiaen is widely regarded as one of the most important composers of the 20th century, known for his unique approach to harmony, rhythm, and melody. His music is challenging for any performer, requiring not only technical skill, but also a deep understanding of his unique musical language.

The pianists presented here demonstrate a remarkable ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s music, bringing out its intricate harmonies, colours, textures and rhythms, as well as its emotional depth.

Yvonne Loriod

Messiaen’s student, muse and second wife, Yvonne Loriod was a highly accomplished pianist in her own right. Many of his piano works were written with her in mind. The Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus (“Twenty Contemplations on the Infant Jesus”) were dedicated to Loriod, and she premiered the work at the Salle Gaveau in Paris in March 1945. Loriod’s playing is known for its clarity and precision, as well as her ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s unique style. She recorded several albums of Messiaen’s piano music, including the complete set of Preludes and the Catalogue d’Oiseaux.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard

French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard is widely recognized as one of the foremost interpreters of Messiaen’s music. Aimard’s connection to Messiaen’s work runs deep, as he was a student of the composer and worked closely with him and his wife Yvonne Loriod. Aimard’s recordings of Messiaen’s piano music are considered some of the most authoritative, and he has performed Messiaen’s works all over the world to critical acclaim.

Angela Hewitt

Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt is perhaps best known for her interpretations of Baroque and Classical music, but she has also made a name for herself in more contemporary repertoire, including Messiaen’s piano music. Her recordings of Messiaen’s music are admired for their technical precision and attention to detail, as well as her ability to bring out the emotional depth of the music.

Steven Osborne

Scottish pianist Steven Osborne has performed Messiaen’s music all over the world, including the Vingt regards and Turangâlila Symphonie. Osborne expertly navigates the intricate harmonies and rhythms in Messiaen’s music with ease, bringing out the complex textures and polyrhythms that are hallmarks of the composer’s style. At the same time, he captures the emotional breadth and spiritual intensity that are crucial features of Messiaen’s music. His performances of the Vingt regards in particular are extraordinarily absorbing, meditative and moving, combining musicality, virtuosity and commitment. (I’ve heard Osborne perform this monumental work twice in London and on both occasions it has been utterly mesmerising and profoundly emotional.)

Tal Walker

For his debut disc, the young Israeli-Belgian pianist Tal Walker included Messiaen’s Eight Preludes. Composed in the 1920s, they are clearly influenced by Debussy with their unresolved or ambiguous, veiled harmonies and parallel chords which are used for pianistic colour and timbre rather than definite harmonic progression. But the Preludes are also mystical rather than purely impressionistic, and look forward to Messiaen’s profoundly spiritual later piano works, Visions de l’Amen (for 2 pianos) and the Vingt regards. Tal Walker displays a rare sensitivity towards this music and his performance is tasteful, restrained yet full of colour, lyricism and musical intelligence.

Other Messiaen pianists to explore: Tamara Stefanovic, Peter Hill, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Ralph van Raat, Benjamin Frith, Peter Donohoe

This article first appeared on InterludeHK

Olivier Messiaen is widely regarded as one of the most important composers of the 20th century, known for his unique approach to harmony, rhythm, and melody. His music is challenging for any performer, requiring not only technical skill, but also a deep understanding of his unique musical language.

The pianists presented here demonstrate a remarkable ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s music, bringing out its intricate harmonies, colours, textures and rhythms, as well as its emotional depth.

Yvonne Loriod

Messiaen’s student, muse and second wife, Yvonne Loriod was a highly accomplished pianist in her own right. Many of his piano works were written with her in mind. The Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus (“Twenty Contemplations on the Infant Jesus”) were dedicated to Loriod, and she premiered the work at the Salle Gaveau in Paris in March 1945. Loriod’s playing is known for its clarity and precision, as well as her ability to capture the essence of Messiaen’s unique style. She recorded several albums of Messiaen’s piano music, including the complete set of Preludes and the Catalogue d’Oiseaux.

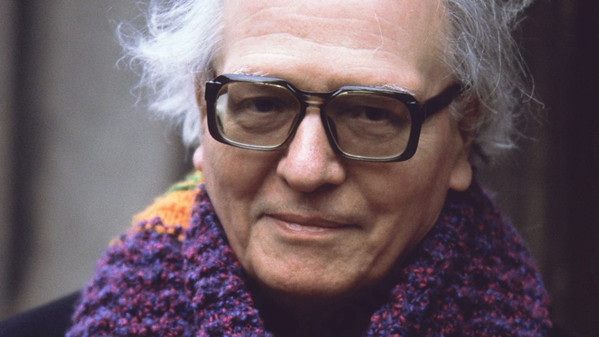

Pierre-Laurent Aimard

French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard is widely recognized as one of the foremost interpreters of Messiaen’s music. Aimard’s connection to Messiaen’s work runs deep, as he was a student of the composer and worked closely with him and his wife Yvonne Loriod. Aimard’s recordings of Messiaen’s piano music are considered some of the most authoritative, and he has performed Messiaen’s works all over the world to critical acclaim.

Angela Hewitt

Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt is perhaps best known for her interpretations of Baroque and Classical music, but she has also made a name for herself in more contemporary repertoire, including Messiaen’s piano music. Her recordings of Messiaen’s music are admired for their technical precision and attention to detail, as well as her ability to bring out the emotional depth of the music.

Steven Osborne

Scottish pianist Steven Osborne has performed Messiaen’s music all over the world, including the Vingt regards and Turangâlila Symphonie. Osborne expertly navigates the intricate harmonies and rhythms in Messiaen’s music with ease, bringing out the complex textures and polyrhythms that are hallmarks of the composer’s style. At the same time, he captures the emotional breadth and spiritual intensity that are crucial features of Messiaen’s music. His performances of the Vingt regards in particular are extraordinarily absorbing, meditative and moving, combining musicality, virtuosity and commitment. (I’ve heard Osborne perform this monumental work twice in London and on both occasions it has been utterly mesmerising and profoundly emotional.)

Tal Walker

For his debut disc, the young Israeli-Belgian pianist Tal Walker included Messiaen’s Eight Preludes. Composed in the 1920s, they are clearly influenced by Debussy with their unresolved or ambiguous, veiled harmonies and parallel chords which are used for pianistic colour and timbre rather than definite harmonic progression. But the Preludes are also mystical rather than purely impressionistic, and look forward to Messiaen’s profoundly spiritual later piano works, Visions de l’Amen (for 2 pianos) and the Vingt regards. Tal Walker displays a rare sensitivity towards this music and his performance is tasteful, restrained yet full of colour, lyricism and musical intelligence.

Other Messiaen pianists to explore: Tamara Stefanovic, Peter Hill, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Ralph van Raat, Benjamin Frith, Peter Donohoe

This article first appeared on InterludeHK