“Schubert’s music is the most human that I know.” – Sir András Schiff, pianist

“I will never quite have the words to express what Schubert’s music has meant to me…and I will never stop looking for them. His ability to convey loneliness — and console in its wake — is perhaps his most ineffable quality…” – Jonathan Biss, pianist

Schubert’s music provides the bridge between the classical and romantic eras. Yet his music was not well known during his lifetime outside of Schubert’s own intimate circle of friends. His piano music was largely neglected right up to the early part of the 20th century when it was given the attention it deserved by pianists such as Artur Schnabel, who can be partly credited for introducing it into the regular concert repertoire with pieces such as the late piano sonatas, the two sets of Impromptus, the Moments Musicaux, and the “Wanderer fantasie”. Today, these works are staples of the pianist’s repertoire, much loved by performers and audiences alike.

Schubert’s musical sensibilities and invention were inspired by the human voice – he wrote over 600 songs – and lyrical melody and long-spung cantabile lines are distinctive elements of all his music.

For the pianist, his music remains an interpretational challenge and the best Schubert players have absorbed the essentials from his songs and chamber music. Because of his proximity, and admiration for Beethoven, there is a tendency among some players to approach his music like Beethoven’s; but Schubert is a composer who speaks more quietly and introspectively, even in his more declamatory moments. The skill in playing his music well is a sensitivity to these aspects without sentimentality.

British pianist Clifford Curzon (1907-1982) had a special affinity for Schubert, fostered by his studies with Artur Schnabel. His performance of Schubert’s last sonata, the D960 in B-flat, is considered by many to be one of the greatest performances ever. In this recording, his concentration and nervous intensity are so palpable it is almost like eavesdropping.

Clifford Curzon Plays Schubert’s Piano Sonata in B-flat major, D.960

A protégé of the great Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter, himself a fine Schubert player, Russian pianist Elisabeth Leonskaja is noted for her performances and recordings of Schubert’s piano music. As an artist, she is unfailingly intelligent, tasteful and musical, whose performances display great refinement, romantic fervour, delicacy, and power, all underpinned by commanding technique.

Franz Schubert: Fantasy in C Major, Op. 15, D. 760, “Wandererfantasie” – Allegro con fuoco ma non troppo (Elisabeth Leonskaja, piano)

No appraisal of Schubert pianists would be complete with András Schiff, who really honours every work, and who has recorded the piano music on Schubert-era instruments, offering listeners an intriguing insight into the range of colours and nuances afforded by Schubert’s writing. Always fastidious in his close attention to the details of the score, Schiff really gets to the heart, soul, and fundamental humanity of Schubert in his playing and brings a compelling intimacy to his performances, even in the largest of concert halls.

The great Romanian pianist Radu Lupu, who died in April 2022, was described by Gramophone magazine as “A lyricist in a thousand”, who placed Schubert’s music at the centre of his repertoire throughout his career. Sensitive to Schubert’s mercurial moods, his playing demonstrates immense control, subtlety of shading and dynamic nuance, an almost ethereal luminosity of sound, and a myriad range of colours which fully reveals Schubert’s inventiveness and imagination, the rich seam of his ideas, and his forward vision.

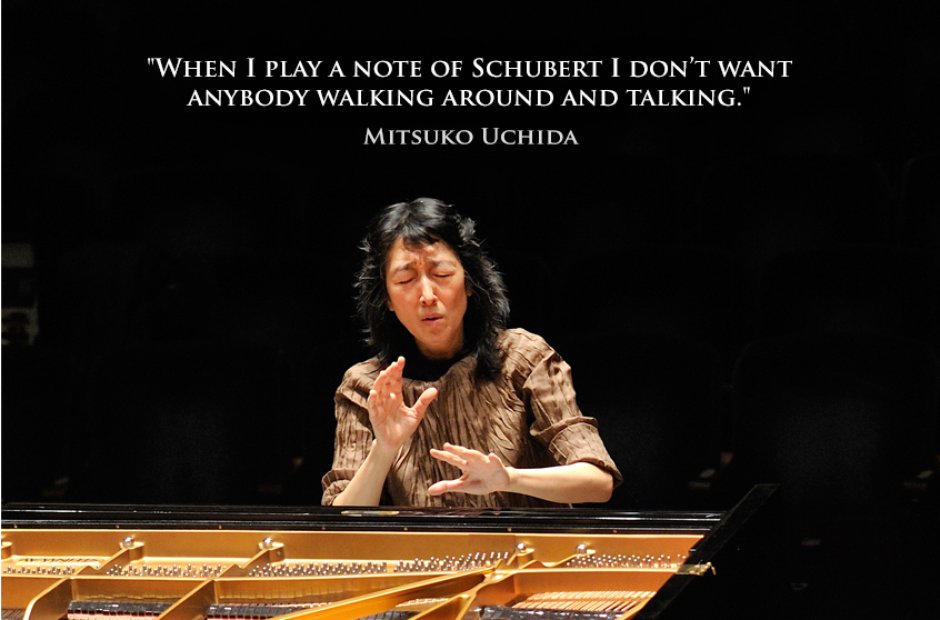

Like András Schiff, Mitsuko Uchida has an unerring ability to bring an intimacy and sense of a conversation to her performances of Schubert’s music, and she does so with clarity, commitment, and a clear sense of the narrative line, the lightness and lyricism, and also the roughness in his music. Uchida is very alert to Schubert’s idiosyncrasies, his chiaruscuro and elusive, shifting moods: beauty and delicacy, poignancy and loneliness abound in her performances of this composer whose music has been a lifelong presence for her.

Other fine Schubert players to explore include Shura Cherkassy, Rudolf Firkusny, Walter Gieseking, Rudolf Serkin, Wilhelm Kempf, Paul Lewis, Maria João Pires, Alexander Lonquich, Imogen Cooper, Krystian Zimerman, Murray Perahia, and of course Alfred Brendel. Of the younger generation, recent discoveries include Inon Barnatan, Yehuda Inbar, Pavel Kolesnikov and Samson Tsoy

An earlier version of this article appeared on the InterludeHK website

Support The Cross-Eyed Pianist

This site is free to access and ad-free, and takes many hours to research, write, and maintain. If you find joy and value in what I do, why not