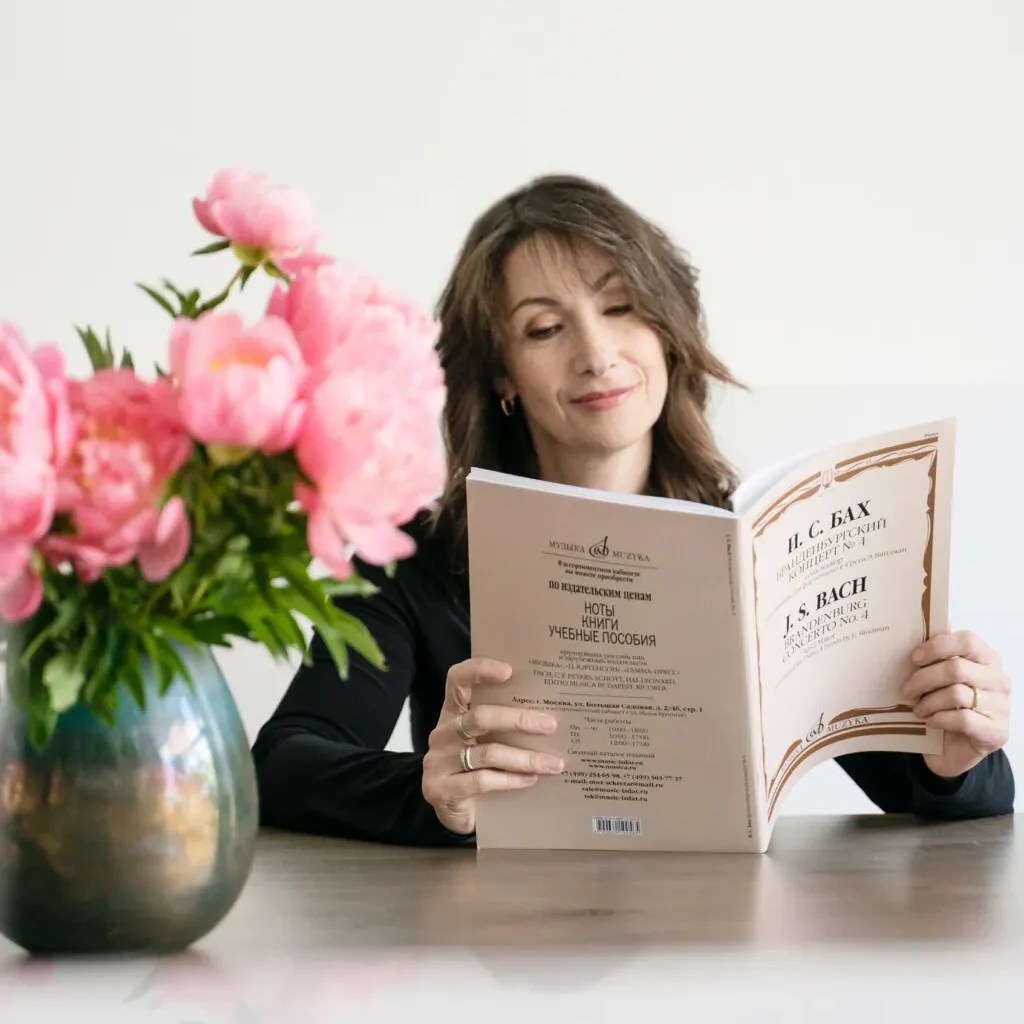

Mirrors & Echoes – Aïda Lahlou, piano

Moroccan pianist Aïda Lahlou makes an exciting and noteworthy recording début with Mirrors and Echoes, released by Resonus Classics on 19 September 2025.

Supported by Les Amis de Maurice Ravel, the album offers a vivid reimagining of Miroirs, placing it in dialogue with lesser-known piano miniatures from across the world to reveal surprising resonances and intertextual connections.

“Whether through spiritual texts, folkloric archetypes, or meditations on nature, each work in the album offers a moment of contemplation and self exploration.” Lahlou says. Drawing on Ravel’s own writing on Miroirs, she adds: “Ravel believed that music should act as a mirror, reflecting back the listener’s own interiority. This album seeks to transport the listener into that reflective space.”

Lahlou’s sensitive interpretation guides us through shifting sonic landscapes and themes of nature, spirituality, memory and transformation. The listening experience is not unlike a musical treasure hunt: Lahlou interweaves Ravel’s visionary five-movement cycle with rare piano miniatures from five continents—some rescued from obscurity, others newly arranged for this recording, like a Brahms motet or a 14th-century Andalucian song, each handpicked for its unexpected kinship with Ravel’s sonic world and its ability to evoke a sense of wonder.

“My hope is that the album’s themes – nature, spirituality, and cross-cultural resonance – can inspire renewed awe for life and the richness of our world, especially at a time when it faces such urgent threats from war, pollution, and climate change.” (Aïda Lahlou)

Born in Casablanca and trained across Europe, Aïda Lahlou brings a multicultural lens to classical repertoire that feels both scholarly and deeply intuitive. The brilliant storytelling, weaving together works by Spendiaryan, Stevenson, Tansman, Garayev, Lecuona, and others, alongside arrangements of Brahms, Siloti and traditional melodies, culminates in a programme that is both exploratory and deeply personal. The result is a compelling artistic statement from a distinctive new voice in classical piano.

Mirrors & Echoes is released on CD and streaming on the Resonus Classics label.

(photo by Ben Reason)

Source: press release

About Aïda Lahlou

Born in Casablanca, pianist Aïda Lahlou began studying piano at the age of five with Yana Kaminska, and won her first international competition at eight. She later studied with Nicole Salmon-Boyer (École Normale Alfred Cortot) before receiving a scholarship to attend the prestigious Yehudi Menuhin School in Surrey. After reading Music at St John’s College, Cambridge, she continued her musical studies at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, studying with Ronan O’Hora and Peter Bithell, and earning a Distinction in Piano Performance (MPerf).

Aïda has performed internationally from a young age, with appearances in venues including Wigmore Hall (London), BOZAR (Brussels), Théâtre National Mohamed V (Rabat), and the Hall of Organ and Chamber Music (Baku). She has performed as soloist with the Orchestre Symphonique Royal, becoming the youngest pianist to do so at the age of twenty, and has performed alongside artists such as Vadim Repin, Roby Lakatos, and Alina Ibragimova.

She has received over 20 national and international awards, most recently the Philip Crawshaw Prize at the Royal Overseas League Music Competition. A passionate educator and communicator, she also directs opera, volunteers with environmental groups, and created an award-winning one-woman show blending classical piano with stand-up comedy.

Praise for Aïda Lahlou

“Aïda Lahlou is a pianist of imagination and poetry, not shy of exploring sonority, colour, or inner voicings.” — The Classical Source

“Vivacious playing.” — Gramophone

“Aida…played with a poetic sensibility of refined beauty and a sense of style and musical intelligence of aristocratic authority.” — Christopher Axworthy

Website: aidalahlou.com