On Friday 12th November, the Polish composer Henryk Gorecki, died aged 76. Gorecki is perhaps best remembered for his Third Symphony, the ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’, a work of sacred minimalism whose dominant themes are motherhood and separation through war. More often than not, this work is considered to be a meditation on the Holocaust, but it is more than that. Each movement is sung by a soprano: the first is a 15th century Polish lament of Mary, mother of Jesus, while the third is a Silesian folk song of a mother searching for her child killed in the Silesian uprisings just after the First War. The second movement is a message written on the wall of a Gestapo cell during the Second War, and has become a ‘soundtrack’ for the Holocaust after a canny film-maker picked it up and used it in the 1990s. Along with Part’s ‘Spiegel im Spiegel’ and ‘Fratres’, this piece more than any other seems to express the inexpressible about this dreadful rupture in modern European history. Sadly, it has been given the “Classic FM treatment”, and its wonder and beauty has now been somewhat devalued through over-exposure.

On Friday 12th November, the Polish composer Henryk Gorecki, died aged 76. Gorecki is perhaps best remembered for his Third Symphony, the ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’, a work of sacred minimalism whose dominant themes are motherhood and separation through war. More often than not, this work is considered to be a meditation on the Holocaust, but it is more than that. Each movement is sung by a soprano: the first is a 15th century Polish lament of Mary, mother of Jesus, while the third is a Silesian folk song of a mother searching for her child killed in the Silesian uprisings just after the First War. The second movement is a message written on the wall of a Gestapo cell during the Second War, and has become a ‘soundtrack’ for the Holocaust after a canny film-maker picked it up and used it in the 1990s. Along with Part’s ‘Spiegel im Spiegel’ and ‘Fratres’, this piece more than any other seems to express the inexpressible about this dreadful rupture in modern European history. Sadly, it has been given the “Classic FM treatment”, and its wonder and beauty has now been somewhat devalued through over-exposure.

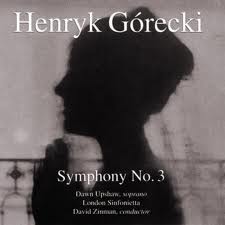

The music is very approachable, perhaps surprisingly so, since Gorecki’s earlier music drew influences from the dissonant works of Stockhausen and Nono, and this has undoubtedly contributed to its popular appeal: it is not “difficult” music to listen to. It is reasonably straightforward in its construction and its harmonies, and makes use of Medieval musical modes. Premiered in 1977, it remained relatively unknown, except amongst connoisseurs, until 1992, when a recording was released with the London Sinfonietta, conducted by David Zinman, with the soprano Dawn Upshaw. It topped the classical charts in the UK and US, and has sold over a million copies.

For me, its Medieval influences, the simplicity of the thematic material and, more than anything else, the soprano line which soars above the orchestra, are what make it so remarkable. It is “tingle factor” music par excellence, and I only need to hear a few bars to feel the hairs rise on the back on the neck. Admittedly, the greater part of its power comes from its association with the Holocaust. Hear a few bars, and one is forced to pause and meditate on that genocide.

Dawn Upshaw’s clean soprano voice is has a wonderful translucence on the 1992 recording. She lacks the heavy vibrato of “old school” sopranos like Dame Janet Baker or Renée Fleming, and there is an innocence in her voice which reinforces the “story” of the music with an almost painful clarity. The rising, scalic motif in the second movement, sung by the soprano and supported by the orchestra, drives the music forward until the voice climaxes on a top A flat. According to the composer, the soprano voice should “tower” over the orchestra, and there are places in this movement where she almost seems to take flight, soaring ethereally above the orchestra. Beneath the voice, the music pulses and “breathes” with an almost audible “lub-dub” beat of the human heart.

It is a shame that the Third Symphony has largely eclipsed Gorecki’s other music, much of which is very fine indeed, and it would be a great pity if he were remembered only for this work, except amongst more esoteric music lovers and scholars. What is certain is that the Third Symphony, and all that it expresses, will continue to resonate with many people for years to come.