Who or what inspired you to take up piano, and pursue a career in music?

The natural long-term choice for me would have been the violin, or at least a string instrument, as my father was a violinist with the Orchestre de Paris and my grandfather was the Principal Violist of the same and of the Paris Opera Orchestra before that. And naturally, violin was my first instrument, but one I abandoned within just months of starting it. I am not entirely certain why – perhaps I should ask my father about it actually – but a new, shiny black lacquered piano appeared in our house one day and I immediately felt pulled to it. I found a world richer than any other I had known until then, one which gave my imagination free rein and which completely absorbed my attention. Piano just felt natural to me, an extension of my own physical and spiritual being, and still does, although I am far from chained to it or obsessive about it. Of course, learning to play the piano while growing up was not always a smooth road, and I was not always disciplined or desirous of playing, especially as the pressure mounted (I did play many hours each day, usually). But I never questioned my choice of instrument, and I feel like it was always the right one for me. And when adults inevitably asked me what I wanted to do later in life, I always said that I wanted to be a pianist. It seemed like a perfectly natural answer and one which was easy for me to imagine, as I already had experience regularly attending concerts and seeing professional pianists solo with the orchestra. With that said, as a teenager and young adult I did question my choice of career, and tried a number of different things before finally making music my life…

Who or what have been the most important influences on your musical life and career?

My parents, of course, who supported and guided me all along. And some of my teachers, some of whose influence was particularly important, of which I can cite Aïda Barenboïm, my first real teacher (Daniel Baremboïm’s mother) who gave me my musical foundations; Elena Varvarova, with whom I massively improved my technique and discipline; Brigitte Engerer, who guided me in a period of uncertainty; Rena Shereshevskaya and Vladimir Krainev, who gave me confidence and brought me to a truly professional level; and Earl Wild, who encouraged me to go where the music took me. I also have to acknowledge Ursula Oppens and James Giles who exposed me to America’s rich musical world which I did not know much about. I was also lucky to learn bits and pieces from, and be supported by, Carlo-Maria Giulini, Maria Curcio, Charles Rosen, and Kurt Masur, all of whom added something important to my musical journey. But then, my life has also been filled by books, films, museums, travel, and people near and far. It is one thing to learn how to play and how to be a good musician, and it is another to experience life and learn about oneself and one’s humanity, which then should come through in the expression of music.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

My career has been unusual, and I have always been out of the system. I have never liked the idea of competition in music, whether in formal or informal terms. Either music is an art or it is a sport, and I don’t believe a sport-like competition is how you hone and find the best artists, even if on occasion you do in a sort of coincidence (although without a doubt, true artists will be true artists no matter how they build their career). The reality is that there is a selection process that occurs anywhere you are, whether formally through a competition or a conservatory entrance audition, or through the acclamation or lack thereof of a public and the press. I don’t personally like to participate in something that to me seems antithetical to the development of the artist and the meaning of music. I say this only because my refusal to play that game has probably penalized me in some ways, and made it harder for me to find my place in the so-called music business.

I have also allowed myself to live life and take the time to learn life from a wide-array of experiences, to find where my truth lies and why I even bother being a musician. And then I also have been active as a teacher, as a concert and festival organizer, and as a recording and film producer of sorts, learning along the way many skills that help me express my personal artistic vision more fully and effectively. I am also quite certain of the joy I feel when sharing something I love with an audience: indeed, music is both uniquely personal and also uniquely communal. For this reason, I hope I will have the chance to share my love of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier with as many people as possible, both through the album as well as through performances down the road.

Which performance/recordings are you most proud of?

While I began my musical life at the very tender age of three, four years old, and began my performance career at ten, I never rushed into making recordings until I felt sure enough of what I had to say, knowing that there was no absolute need to engrave music permanently that had already been recorded by others before, unless there was another compelling reason to do so. Perhaps surprisingly at this stage of life, my recording of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier is my first solo release, but I am not shy of saying that I am exceedingly proud of it and happy to have made it just that way. And while my playing of Bach has already changed since I made the recording, I feel that it is a very accurate representation of who I am as a musician.

I am also still proud and honoured to have given the World Premiere performances and recording of Beethoven’s Piano Trio Hess 47 with my Beethoven Project Trio back in 2009 in Chicago and New York, an adventure forever engraved in my memory.

Which particular works do you think you play best?

I like to get under the skin of the composers whose music I play. When I begin to explore a sound world, I want to go deep and feel the sensitivities and emotions of the composer who wrote that music, which is one of the reasons I like to isolate a composer and focus very intensely on that one artist, usually making pilgrimages to the places where that composer lived and worked and reading a lot, along with exploring as much of his or her music as possible. For big composers, I do think it’s a very valuable experience to really go deep, which is what I did with Bach and his Well-Tempered Clavier, and is what I am doing now with Beethoven as I prepare to record his complete sonatas. Those two composers will always be very close to my musical heart, as well as Rameau, Mozart, Chopin, Debussy and Ravel. I also love Brahms, but am taking my time to take a full dive into his world. More importantly, life is usually circular, and I approach these composers many times, over time and in due time, and until the time I feel ready to go straight to the heart of what they mean to me. As far as specific works that I play best, I don’t think that is as relevant as just feeling close to a composer’s musical language and being free to express my own sensitivity through that adopted language.

How do you make your repertoire choices from season to season?

I don’t play the seasons game. Music and a musical life have to remain organic, natural, flowing. I cannot force myself to think in terms of seasons. I simply go where my passion takes me and let things fall into place as they will. I am human, and more importantly a musician, not a bureaucrat. As long as I have joy to play a program, I will do so. If for any reason I lose that joy, the program will change. What I do guarantee is that I will show up, barring any impossible situation, where I said I would, and I am always game for a challenge. But I will never do anything that will threaten the joy of music making, and the desire to share something that rings true to me at a specific moment. The idea that I can program something more than one, two or three years in advance rings hollow to me, with the probable exception of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, which I have never grown tired of and don’t expect to. But clearly I also love to take my time to explore one work or one composer, and that usually lasts two or three seasons at least…

Do you have a favourite concert venue to perform in and why?

No. As long as there is a minimal amount of climate comfort, and a decent piano, and more importantly a curious audience, I am happy. But I will say that I never had as much pleasure as I did when recording the Well-Tempered Clavier in Weimar’s historic Jakobskirche and on a very unique Hamburg Steinway D that I had found in Paris, through Régie Pianos. Everything about the acoustic and physical experience there was satisfying, and I suppose that’s a good thing when it comes to making a permanent record!

Who are your favourite musicians?

I don’t know. There are lots of musicians whom I admire, and who have made some great recordings, who have performed some memorable concerts, who have moved me, dead or alive, at one time or another of my life. Some musicians have done it more regularly than others, but it’s so subjective, even to me! And truly, for the most part, there is no debate to be had on most of the great musicians. In no particular order, Artur Rubinstein, Josef Hofmann, Dinu Lipatti, Vladimir Horowitz, Claudio Arrau, Marcelle Meyer, Pau Casals, Jascha Heifetz, Henryk Szeryng, Georg Solti, Leonard Bernstein… to stay only with the dead, and to remain terribly incomplete. But I love going down rabbit holes and listening, either to radio, one of the streaming services, or just randomly picking through my record collection, and acquainting or reacquainting myself with a musician. But I am not a guru seeker, so while I enjoy listening, going to concerts, and so on, I am also happy with silence sometimes, which is a great teacher of music.

What is your most memorable concert experience?

I’ve been to many. A performance of Eugène Onégin with Valery Gergiev conducting his Mariinsky orchestra and singers in Paris some twenty years ago has stayed with me emotionally. Deeply memorable also was a masterclass given by Kurt Masur in New York where he showed the arm-waving student conductors how to conduct without even moving his arms (and of course do it better)! It taught me the power of intention and focus.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

There are several sides to success and different ways of understanding the meaning of success as a musician. For me, first, it is being able to express myself from the fount of my inner truth, in other words, it has to ring true to me first, and remains entirely personal, involving no one else, and which is only possible following a long inner journey of discovery and experience. Second, it is succeeding in the practical sense, having the ability to make albums, to perform, and to transmit what one has learned, in such a way as to be free from need and free to be creative. But that sometimes comes and goes with life’s many ups and downs! So then I hold on to my first precept.

What do you consider to be the most important ideas and concepts to impart to aspiring musicians?

Stop practicing! Begin living! Seriously, if you know how to play scales and arpeggios, know how to read music, and have covered some basic repertoire from different periods, your basic instrumental education is over. I think way too many musicians try the athletic approach to music, and think they have to be as good if not better technically than the current stars. Perhaps so, in a sense, okay, fine. But a big part of learning to be a good performer, even a good technician, comes from loosening up and taking a step back. Live! Love! Make mistakes! Learn! What else is true music, true art about, if it is not about life? The practice room is too small to let life in. Don’t let life slip by, and find your truth through experience, through the highs and the lows of it all. Confront yourself to reality, not theory. The conservatory is not the place to learn to be a musician, but only a technician. That’s fine for a bit but don’t expect too much from it, if you really have it in you to be a musician. Stop studying as soon as you can, and you’ll have a greater chance of becoming a musician someday.

Where would you like to be in 10 years’ time?

A good place, on a cooler and calmer planet, in harmony with my environment and humanity both physically, emotionally and spiritually.

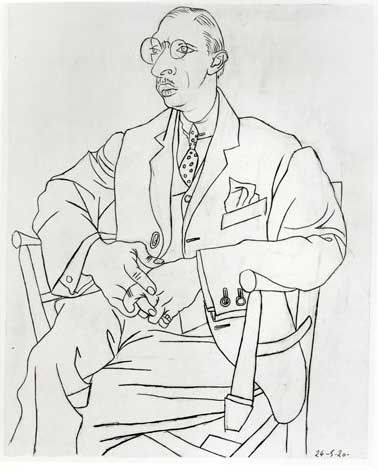

A concert pianist since his formal debut at age ten in Paris, George Lepauw has performed ever since as a recitalist, chamber musician, vocal collaborator, and soloist with orchestra. He also occasionally collaborates with musicians from other musical genres, including cabaret, musical theater, traditional Chinese and Persian music, flamenco, blues, and pop.

Read more