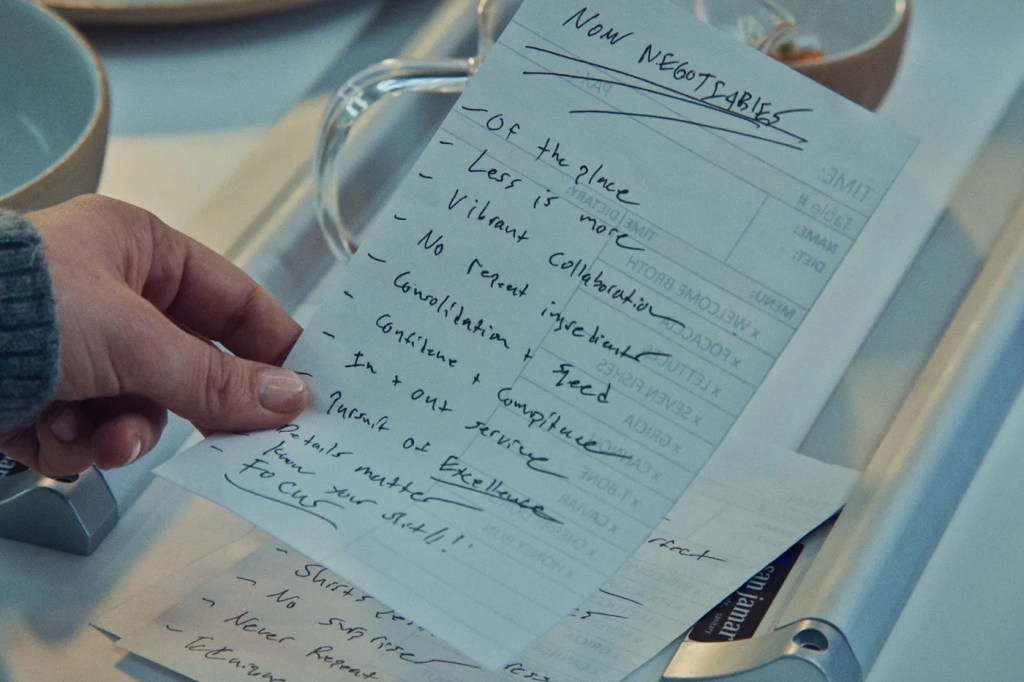

This post is inspired by Episode 2 of Season 3 of The Bear, a drama series about a young chef, Carmy Berzatto, trained in the fine dining world, who comes home to Chicago to run his family sandwich shop after a heartbreaking death in his family. By the third series, the noisy sandwich shop has been transformed into an elegant fine dining restaurant and Carmy is seeking a coveted Michelin star. In this episode, Carmy draws up a massive list of what he calls “non-negotiables”: the things that the restaurant must do on a consistent basis to achieve greatness.

Looking through the list, while some of the non-negotiables are explicitly related to cheffing and kitchen/restaurant management, a number could apply equally to the musician in pursuit of consistency and excellence in their practice and performance of music.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that noticeable progress, at whatever level you play, comes from a well-organised, consistent, focussed and thoughtful approach to practicing. It’s not quantity (of hours spent practicing) but the quality of practicing that counts.

This, for me, is where Carmy’s non-negotiables come in.

These principles, though originally used in contexts like culinary arts or other forms of craftsmanship, translate beautifully into music practice.

Change the Menu Every Day

Boredom is the enemy of progress, so incorporate variety into your daily practice routine. Instead of doing the same exercises daily or beginning with the same piece in the same place, try different approaches to challenge yourself in new ways.

No Repeat Ingredients

Avoid getting stuck in repetitive patterns. Constantly seek new skills, concepts, and exercises to enrich your practice. Challenge yourself with new materials rather than only practicing familiar ones. For example, if you’re used to playing pieces in a specific genre, try something completely different, like a jazz standard if you usually play classical repertoire.

Know Your Sh*t!

Fully understand the fundamentals of music, including theory, notation, and instrument mechanics. This knowledge helps you interpret music more intelligently and aids problem-solving

Respect Tradition

Appreciate and study the foundational pieces and techniques of your instrument. Understanding the work of past masters and traditional techniques gives you a solid framework of musical knowledge. BUT don’t let tradition or orthodoxy stand in the way of your approach to your music making or your personal interpretative choices. Remember, you can use the pedal in Bach!

Push Boundaries

Explore new techniques, unusual genres, or challenging pieces that lie just outside your comfort zone. This pushes your growth and helps you develop your own musical voice and autonomy as a musician.

Technique, Technique, Technique

Build a strong technical foundation. Mastering technique gives you control, precision, and freedom to express yourself without being limited by physical obstacles. But always remember that technique should serve the music, not the other way. Don’t let technique become the be all and end all of your music practice.

It’s Not About You

Remember that music serves a larger purpose – whether it’s storytelling, emotional expression, or creating a shared experience. Approach practice as a way to honour the music, not just to showcase your skills. If we become too emotionally attached to our music and instrument, it can cloud our objectivity: don’t let a bad practicing session translate into general negativity. Reflect and move on.

Additionally, be open-minded about taking advice from others – teachers, mentors, trusted colleagues and friends.

Less is More

Instead of overplaying or adding unnecessary elements, focus on clarity and purpose in each note. Embrace simplicity and avoid cluttering your performance or practice. For example, avoid false sentiment or the over-use of rubato to add more “expression” – it can sound contrived.

Details Matter

It goes without saying that we should pay attention to small details- dynamics, articulation, tempo changes, phrasing, pedal markings. These details bring music to life and distinguish good from great performances.

Confidence and Competence

Cultivate both confidence and competence through thorough preparation (“deep practicing”). Knowing you’ve practiced well allows you to play with conviction, which listeners can feel.

Constantly Evolve Through Passion and Creativity

Approach each practice session with curiosity, open-mindedness, and a willingness to improve. Use your passion to fuel your creativity and push yourself to develop.

Jennifer Griffin Gaul is a US-based pianist and educator. She holds a Master of Music in piano pedagogy and performance from the University of Texas at Austin.

Jennifer Griffin Gaul is a US-based pianist and educator. She holds a Master of Music in piano pedagogy and performance from the University of Texas at Austin.